Robustness between the worst and average case

As machine learning systems become increasingly implemented in safety-critical applications, such as autonomous driving and healthcare, we need to ensure these systems are reliable and trustworthy. For example, we might wish to determine whether a car’s camera-based autopilot system can correctly classify the color of the light even in the presence of severe weather conditions, such as snow. Consider that the average snowy day looks something like the following:

Overall, the visibility is not too bad, and we can guess that these weather conditions do not present too much of an issue for the car’s autopilot system. However, every once in a while, we might get a snowy day that looks more like this:

The visibility is much worse in this scenario, and these conditions might be more difficult for the car’s autopilot system to safely navigate. However, the traffic light color, as well as most of the objects on the road, can still be identified, and we would hope that the autopilot would be able to operate correctly in these conditions. Finally, very rarely, we might have a snow squall like the following:

These conditions are so extreme that a human driver would probably need to pull over to the side of the road rather than attempt to drive in with such little visibility. Therefore, we probably should not require the autopilot system to be robust to such conditions. Now we ask the question, how should we evaluate the robustness of the the car’s autopilot to severe weather conditions?

Existing methods for evaluating the robustness of a machine learning model to perturbed inputs (e.g. images that have been corrupted due to severe weather) are largely based on one of two notions. Average-case robustness, measures the model’s average performance on randomly sampled perturbations. In the autopilot example, for instance, we could randomly sample a bunch of images from all days recorded snow precipitation, and measure the average accuracy of the traffic light detection on those days. If most of those samples look like the first image shown above, we should expect the system’s average robustness to be pretty good. This notion of robustness, however, doesn’t tell us much about how our autopilot system will operate on more extreme conditions as depicted in the second and third images.

Alternatively, worst-case robustness, or adversarial robustness, measures the model’s worst-case performance across all possible perturbations. For example, the worst-case performance of the autopilot system might be the result of navigating in the conditions depicted by the third image, displaying the snow squall. In this case, we should expect the system’s worst-case robustness to be pretty bad. But as we mentioned previously, we may not care so much if the system is able to navigate the worst-case conditions shown in the third image.

So then, how do we best measure the robustness of the system to conditions like those shown in the second image, i.e. conditions worse than average, but not the worst possible conditions? In this blog post, we present an alternative method for evaluating the test-time performance of machine learning models that measures robustness between the worst and average case, or intermediate robustness.

A simple example: robustness to Gaussian noise

To further motivate the notion of intermediate robustness, consider the simple scenario in which we are interested in evaluating the robustness of an image classification model to Gaussian noise applied to the input images. The image below is a sample from the ImageNet validation dataset, which an image classifier trained on the ImageNet training dataset correctly classifies as “pizza”.

Given ten thousand random samples of Gaussian noise, the model classifies 97% of these noised images correctly, including the image below. Given the model correctly classifies a large majority of the randomly perturbed images, evaluating according to average-case robustness will place most weight on “easy” noise samples like this image.

The following image shown below illustrates an example of a randomly noised image that the model incorrectly classifies as “soup bowl”. Evaluating according to average-case robustness will place not put much weight on these samples that are harder for the model to classify correctly.

What if we want to evaluate the model’s robustness on a stricter level than average-case robustness? Evaluating the image classifier according to worst-case robustness doesn’t make much sense for this particular noise distribution, because the worst-case noise could be an arbitrarily large amount of noise with extremely low probability due to the Gaussian distribution being unbounded. A more practical evaluation of robustness would consider something stricter than simply average performance on random perturbations, but not quite as strict as adversarial robustness, which is exactly what our intermediate robustness metric enables.

An intermediate robustness metric

We’ll now go into the details of how we formulate an intermediate robustness metric. We start by observing that we can naturally generalize average-case and worst-case robustness under one framework. To show this, we will make use of the mathematical definition of an \( L^p \)-norm of a function \( f \) on a measure space \( X \): \( ||f||_p = (\int_X |f|^p )^{(1/p)} \). However, to differentiate this from the use of \( \ell_p \)-norm balls as perturbation sets in adversarial robustness, we will from here on out refer this definition as a \(q \)-norm of a function. Ultimately, average and worst-case robustness can be generalized by taking the \( q \)-norm of the loss function over the perturbation distribution, where the loss just measures how well the model performs on the perturbed data. The setting of \( q=1 \) results in average-case robustness, whereas the setting of \( q = \infty \) results in worst-case robustness, because by definition the \( L^\infty \)-norm is given by the pointwise maximum of a function. Then, any value of \( q \) between \( 1 \) and \( \infty \) results in intermediate robustness. This is more formally written below:

Define a neural network \( h \) with parameters \( \theta \), and a loss function \( \ell \) that measures how different the model predictions are from the true label \( y \) given an input \( x \). Consider we are interested in measuring the robustness of this model to perturbations \( \delta \) from some perturbation distribution with density \( \mu \). Now consider the following expectation over the \( q \)-norm of the loss according to this perturbation density, $$ \mathbf{E}_{x, y \sim \mathcal{D}} \Big[ ||\ell(h_\theta(x+\delta), y)||_{\mu, q} \Big], $$ where the \( q \)-norm of the loss with perturbation density \( \mu \) is the following: $$ ||\ell(h_\theta(x+\delta), y)||_{\mu, q} = \mathbf{E}_{\delta \sim \mu} [|\ell(h_\theta(x+\delta), y)|^q]^{1/q} = \Big( \int |\ell(h_\theta(x+\delta), y)|^q \mu(\delta)d\delta) \Big)^{1/q}.$$ Assuming a smooth, non-negative loss function, this expectation corresponds to the expected loss on random perturbations (average-case) when \( q = 1 \), $$ || \ell(h_\theta(x+\delta), y) ||_{\mu, 1} = \mathbf{E}_{\delta \sim \mu} [\ell(h_\theta(x+\delta), y)], $$ and the expected maximum loss over all possible perturbations (worst-case) when \( q = \infty \), $$ || \ell(h_\theta(x+\delta), y) ||_{\mu, \infty} = \text{max}_{\delta \in \text{Supp}(\mu)}[\ell(h_\theta(x+\delta), y)].$$

Intuitively, as we increase \( q \), more emphasis will be placed on high loss values, as the losses become more strongly “peaked” due to the exponent of \( q \). And so by increasing \(q \) from \( 1 \) to \( \infty \), we enable a full spectrum of intermediate robustness measurements that are increasingly strict by placing more weight on high loss values. This formulation allows us to evaluate a model’s robustness in a wide range between the two extremes of average and worst case performance.

Approximating the metric using path sampling

In most cases, we have to approximate the metric we just defined, which cannot be calculated exactly because it requires computing a high-dimensional integral over the perturbation space. Ultimately, we approximate the integral using the path sampling method [Gelman and Meng, 1998], but to motivate why this is important, we’ll first give an example of a naive, yet suboptimal, way of estimating the integral.

Monte Carlo estimator

For illustration purposes, let’s consider approximating the integral \( \int_a^b f(x)^q \mu(x)dx \) for an arbitrary function \( f \) and probability density \( \mu \). Recall that the integral of a function can be interpreted as calculating the area below the function’s curve. We could pick a random sample \( x \), evaluate the function \( f(x)^q \) at \( x \) and multiply by \( (b-a ) \) to estimate the area. However, using just one sample, this will likely underestimate or overestimate the area. If we instead pick many samples and take the average of their estimates, with enough samples this theoretically should eventually converge to something close to the desired integral. This is known as the Monte Carlo estimator, and can be visualized in the plot below for the function \( f(x)^q \) with \( q = 1 \).

Now let’s see what this plot looks like for \( q=2 \). We see that values of \( x \) for which the value \( f(x) \) is large make a larger contribution to the integral. However, because these values of \( x \) have a lower probability of being sampled, random sampling places a disproportionate amount of weight on estimates from \( x \) with lower values of \( f(x) \).

As we continue to increase the value of \( q \), as shown in the plot below for \( q=3 \), we can see that Monte Carlo sampling will be increasingly insufficient to approximate this integral well.

Translating this back to our integral of interest, when the perturbation density is concentrated in a region with low loss values, the Monte Carlo estimator will be less capable of producing an accurate approximation of the integral when we want to evaluate intermediate robustness for larger values of \( q \).

Path sampling estimator

To better approximate the integral for large values of \( q \), we need to sample perturbations that contribute more largely to the integral (e.g. result in higher loss values) more frequently. Path sampling is one method that boosts the frequency of more “important” samples by sampling from a “path” of alternative densities that encourages samples where the integrand is large.

The path sampling estimator of the intermediate robustness metric ultimately takes the form of the geometric mean of the losses given the sampled perturbations from these alternative densities, which are annealed to follow an increasingly “peaked” distribution. Practically, these samples can be drawn using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. The path sampling estimator is written more formally below:

Consider the following class of densities, $$ p(\delta|t) \propto \ell(h_\theta(x+\delta),y)^t \mu(\delta),$$ and construct a path by interpolating \( t^{(i)} \) between 0 and \( q \) and sampling a perturbation \( \delta^{(i)} \) from \( p(\delta|t^{(i)}) \) using MCMC. Then, the path sampling estimator of the intermediate robustness metric is the following geometric mean, $$ \hat{Z}_\text{Path sampling} := \Big( \prod_{i=1}^m \ell \big( h_\theta(x+\delta^{(i)}), y \big) \Big)^{1/m}.$$

Evaluating the intermediate robustness of an image classifier

Now that we have introduced a metric for evaluating the intermediate robustness of a model, along with methods for approximating this metric, let’s evaluate the performance of a model at different robustness levels. We’ll see that the intermediate robustness metric interpolates between measurements of average and the worst-case robustness, providing a multitude of additional ways in which we can measure a model’s robustness, and we’ll empirically show the advantage of the path sampling estimator over the Monte Carlo estimator.

Because it is a setting commonly considered in the adversarial (worst-case) robustness literature, consider evaluating the robustness of an image classifier to perturbations \( \delta \) uniformly distributed within the \( \ell_\infty \)-norm ball with radius \( \epsilon \) (i.e. each component of \( \delta \) is uniformly distributed between \( [-\epsilon, \epsilon] \)).

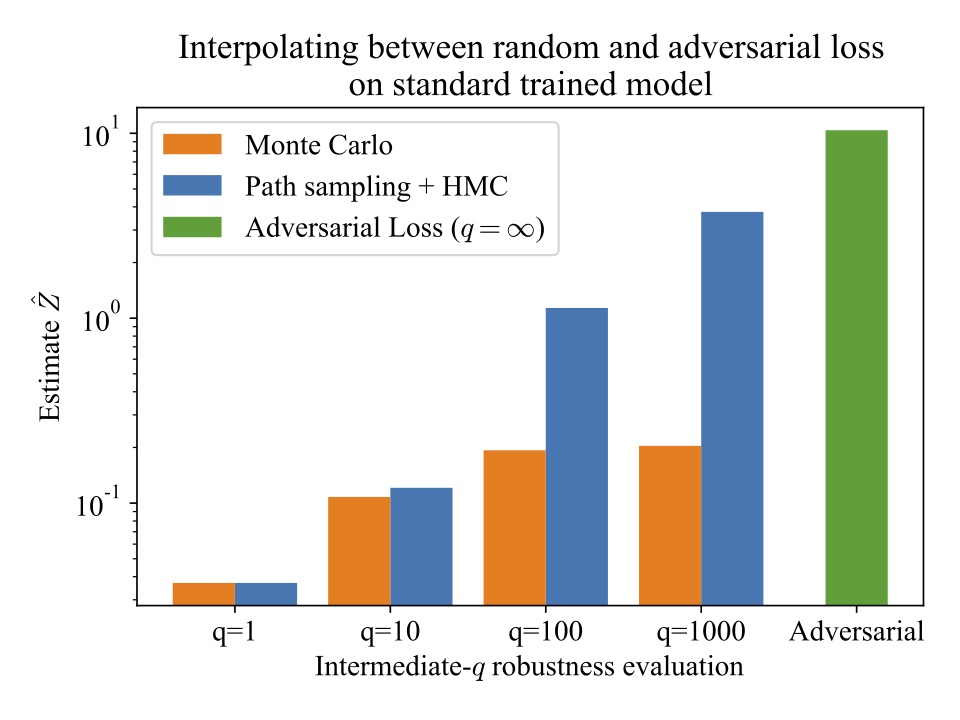

In the figure below, we plot the test-time performance of an image classifier, trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset, using our intermediate robustness metric for different values of \( q \).

This figure shows that our proposed intermediate robustness metric does indeed capture the gap between the two existing robustness metrics, effectively interpolating between average-case robustness (\( q=1 \)) and worst-case (adversarial) robustness measurements when increasing the value of \( q \) from left to right.

We can also compare the Monte Carlo and path sampling estimators for different values of \( q \). This figure illustrates that while both of the approximation methods result in a similar estimate for \( q=1 \), for larger values of \( q \), path sampling results in a higher, more accurate estimate of the intermediate robustness metric, more closely approaching the adversarial loss, when compared to Monte Carlo sampling.

The benefit of the path sampling estimator can be further shown in the figure below, which plots the convergence of the Monte Carlo sampling and path sampling estimates of the intermediate robustness metric given an increasing number of samples.

| Convergence with \( q=1 \) | Convergence with \( q=100 \) |

|---|---|

|

|

Again, when approximating the robustness metric for \( q=1 \), shown on the left, both estimators converge to the same value with relatively few iterations. However, when approximating the intermediate robustness metric for \( q=100 \), shown on the right, the Monte Carlo sampler results in estimates that are consistently lower and less accurate than those of path sampling, even with a large number of samples.

Training for different levels of robustness

We can also train machine learning models according to specific levels of robustness by choosing a value of \( q \) and minimizing the intermediate robustness objective. However, training intermediate robust models is computationally challenging because a non-trivial number of perturbation samples is needed to accurately estimate the robustness objective, even when using the path sampling method. While evaluating models simply requires one iteration over the test dataset, training requires multiple iterations over the training dataset, resulting in an extremely expensive procedure when effectively multiplying the dataset size by the number of perturbaton samples.

Due to this computational complexity, we train an image classifier on the simpler MNIST dataset (using the same perturbation set) to minimize the intermediate robustness objective for different values of \( q \) (approximated using path sampling). We train one model with \( q=1 \), which is just like training with data augmentation (training on randomly sampled perturbations), and we train one model with \( q=100 \), which is somewhere in between training with data augmentation and adversarial training (training on worst-case perturbations).

We evaluate the intermediate and adversarial robustness of each of the final trained models, the results of which can be seen in the figure below.

| Training with \( q=1 \) | Training with \( q=100 \) |

|---|---|

|

|

While the model trained with \( q=1 \), shown on the left, and the model trained with \( q=100 \), shown on the right, have similar performance when evaluated at less strict robustness levels, \( q=1 \) and \( q=10 \), the model trained with \( q=100 \) is much more robust when comparing the stricter \( q=1000 \) and adversarial robustness measurements.

Ultimately, the main takeaway from training using the proposed intermediate robustness objective is that the choice of \( q \) allows for fine-grained control over the desired level of robustness, rather than being restricted to average-case or worst-case objectives.

Conclusion

We’ve introduced a new robustness metric that allows for evaluating a machine learning model’s intermediate robustness, bridging the gap between evaluating robustness to random perturbations and robustness to worst-case perturbations. This intermediate robustness metric generalizes average-case and worst-case notions of robustness under the same framework as functional \( q \)-norms of the loss function over the perturbation distribution. We introduced a method for approximating this metric using path sampling, which results in a more accurate estimate of the metric compared to naive Monte Carlo sampling when evaluating at robustness levels approaching adversarial robustness. Empirically we showed that by evaluating an image classifier on additive noise perturbations, the proposed intermediate robustness metric enables a broader spectrum of robustness measurements, between the least strict notion of average performance on random perturbations and the most conservative notion of adversarial robustness. Finally, we highlighted the potential ability to train for specific levels of robustness using intermediate-\( q \) robustness as a training objective. For additional details, see our paper here and code here .

References

Andrew Gelman and Xiao-Li Meng. Simulating normalizing constants: From importance sampling to bridge sampling to path sampling. Statistical science, pages 163–185, 1998.

Bennett, Charles H. “Efficient estimation of free energy differences from Monte Carlo data.” Journal of Computational Physics 22.2 (1976): 245-268.

Meng, Xiao-Li, and Wing Hung Wong. “Simulating ratios of normalizing constants via a simple identity: a theoretical exploration.” Statistica Sinica (1996): 831-860.

Simon Duane, Anthony D Kennedy, Brian J Pendleton, and Duncan Roweth. Hybrid monte carlo. Physics letters B, 195(2):216–222, 1987

Acknowledgements

This blog post is based on the NeurIPS 2021 paper titled Robustness between the worst and average case , which was joint work with Anna Bair , Huan Zhang , and Zico Kolter . This work was supported by a grant from the Bosch Center for Intelligence.