Tight Lower Bound for Directed Cut Sparsification

In this blog post, I will begin by introducing the concept of cut sparsifier for a given graph \(G\), which has been a powerful tool in the design of graph algorithms. Following that, I will present a tight lower bound for the directed cut sparsifier of a balanced directed graph, which is unknown in the previous literature. This blog post is based on joint work with Yu Cheng and David P. Woodruff, and an extended version of this research has been accepted for publication at PODS 2024.

Introduction

What is a (for-all) cut sparsifer?

The notion of

cut sparsifiers

has been extremely influential. It was introduced by Benczúr and Karger [Benczúr and Karger, 1996] : Given a graph \( G = (V, E, w) \) with \( n = |V| \) vertices, \( m = |E| \) edges, edge weights \( w_e \ge 0 \), and a desired error parameter \( \epsilon > 0 \), a \( (1 \pm \epsilon) \)

cut sparsifier

of \( G \) is a subgraph \( H \) on the same vertex set \( V \) with (possibly) different edge weights, such that \( H \) approximates the value of every cut in \( G \) within a factor of \( (1 \pm \epsilon) \).

Benczúr and Karger [Benczúr and Karger, 1996] showed that every undirected graph has a \( (1 \pm \epsilon) \) cut sparsifier with only \( O\left(\frac{n \log n}{\epsilon^2}\right) \) edges. This was later extended to the stronger notion of

spectral sparsifiers

[Spielman and Teng, 2011], and the number of edges was improved to \( O\left(\frac{n}{\epsilon^2}\right) \) [BSS, 2012].

What is a for-each cut sketch?

For very small values of \( \epsilon \), the \( 1/\epsilon^2 \) dependence in known cut sparsifiers may be prohibitive. Motivated by this, the work of [ACK+, 2016] relaxed the cut sparsification problem to outputting a data structure \( D \), such that for any fixed cut \( S \subset V \), the value \( D(S) \) is within a \( (1 \pm \epsilon) \) factor of the cut value of \( S \) in \( G \) with probability at least \( 2/3 \). Notice the order of quantifiers — the data structure only needs to preserve the value of any fixed cut (chosen independently of its randomness) with high constant probability. Formally, we have

Definition 1. (For-Each Cut Sketch) Let \( 0 < \epsilon < 1 \) . We say \(\mathcal{A}\) is a \((1\pm\epsilon)\) for-each cut sketching algorithm if there exists a recovering algorithm \(f\) such that, given a directed graph \(G = (V, E, w)\) as input, \(\mathcal{A}\) Can output a sketch \( \mathrm{sk}(G) \) such that, for each \( \emptyset \subset S \subset V \), with probability at least \( \frac{2}{3} \), \[ (1 - \epsilon) \cdot w(S, V \setminus S) \le f(S, \mathrm{sk}(G)) \le (1 + \epsilon) \cdot w(S, V \setminus S). \] Here \(w(S, V \setminus S) \) denote the total weights of the cut edges between \(S\) and \(V \setminus S \).

This is referred to as the for-each model, and the data structure is called a for-each cut sketch . Surprisingly, [ACK+, 2016] showed that every undirected graph has a \( (1 \pm \epsilon) \) for-each cut sketch of size \( \tilde{O}(n/\epsilon) \) bits, reducing the dependence on \( \epsilon \) to linear. They also showed an \( \Omega(n/\epsilon) \) bits lower bound in the for-each model.

What is the case for a directed graph?

While the above results provide a fairly complete picture for undirected graphs, a natural question is whether similar improvements are possible for directed graphs. This is the main question posed by [CCPS, 2021]. For directed graphs, even in the for-each model, there is an \( \Omega(n^2) \) lower bound without any assumptions on the graph: consider the following example in a directed bipartite graph, we can actually choose \( S \) to make the cut only contain exact one edge \((u, v)\) for every edge \((u, v)\) in this graph, which means the sketch must have size \(\Omega(n^2)\).

Figure 1: The cut \(S\) only contains a single edge \((u, v)\),so any sparsifier must contain this edge

Figure 1: The cut \(S\) only contains a single edge \((u, v)\),so any sparsifier must contain this edge

Motivated by this, [EMPS16, IT18, CCPS21] introduced the notion of \( \beta \)-balanced directed graphs, meaning that for every directed cut \( (S, V \setminus S) \), the total weight of edges from \( S \) to \( V \setminus S \) is at most \( \beta \) times that from \( V \setminus S \) to \( S \). Formally, we have

Definition 2. (\( \beta \)-Balanced Graphs) A strongly connected directed graph \(G = (V, E, w)\) is \(\beta\)-balanced if, for all \(\emptyset \subset S \subset V\), it holds that \(w(S, V \setminus S) \le \beta \cdot w(V \setminus S, S)\).

The notion of \( \beta \)-balanced graphs turned out to be very useful for directed graphs, as [IT18, CCPS21] showed an \( \tilde{O}(n \sqrt{\beta}/\epsilon) \) upper bound in the for-each model, and an \( \tilde{O}(n \beta/\epsilon^2) \) upper bound in the for-all model, thus giving non-trivial bounds for both problems for small values of \( \beta \). The work of [CCPS, 2021] also proved lower bounds: they showed an \( \Omega(n \sqrt{\beta/\epsilon}) \) lower bound in the for-each model, and an \( \Omega(n \beta/\epsilon) \) lower bound in the for-all model. While their lower bounds are tight for constant \( \epsilon \), there is a quadratic gap for both models in terms of the dependence on \( \beta \). Therefore, below we ask the main question we will focus on in this blog post.

Question 1. What is the tight space complexity of for-each and for-all cut sketch in a \(\beta\)-balanced directed graph?

Tight Lower Bound for For-Each Cut Sketch in a \(\beta\)-Balanced Directed Graph

In this section, we will give our main result, a tight \(\tilde{\Omega}(n \sqrt{\beta} / \epsilon) \) lower bound on the output size of \((1 \pm \epsilon) \) for-each cut sketching algorithms (Definition 2). Formally, we have

Theorem 1. Let \( \beta \ge 1 \) and \(0 < \epsilon < 1\). Assume \( \sqrt{\beta}/\epsilon \le n / 2 \). Any \( (1 \pm \epsilon) \) for-each cut sketching algorithm for \(\beta\)-balanced \(n\)-node graphs must output \( \tilde{\Omega}(n \sqrt{\beta}/ \epsilon) \) bits.

We remark in our full version of the paper , we also give a tight \( \tilde{\Omega}(n \beta / \epsilon^2) \) lower bound for the for-all cut sketch. For more information we refer the readers there.

A common technique we use for the two problems is communication complexity games that involve the approximation parameter \(\epsilon\). For example, suppose Alice has a bit string \(s\) of length \( (1/\epsilon^2) \), and she can encode \(s\) into a graph \(G\) such that, if she sends Bob a \( (1\pm\epsilon) \) (for-each or for-all) cut sketch to Bob, then Bob can recover any specific bit of \( s \) with high constant probability. By communication complexity lower bounds, we know Alice must send \( \Omega(1/\epsilon^2) \) bits to Bob, which gives a lower bound on the size of the cut sketch. In the for-each sketch, we will consider the following Index problem

Lemma 1. (Index) Suppose Alice has a uniformly random string \(s \in \{-1, 1\}^n\) and Bob has a uniformly random index \(i \in [n]\). If Alice sends a single (possibly randomized) message to Bob, and Bob can recover \(s_{i}\) with probability at least \(2/3\) (over the randomness in the input and their protocol), then Alice must send \(\Omega(n)\) bits to Bob.

Intuitively, consider a basic encoding method [ACK+15, CCPS21] where each bit \(s_i\) is represented by an edge \((u, v)\) in a bipartite graph \(G(L, R, E)\), with a weight of either 1 or 2. After encoding, we query the edges leaving a set \(S = {u} \cup (R \setminus {v})\) to decode the bit \(s_i\) which the edge \((u, v)\) represents (see Figure 1 for an example). In this setup, to make the bipartite graph \(\beta\)-balanced, the backward edges from \(R\) to \(L\) are assigned a weight of \(1/\beta\), and these backward edges contribute to a cut value of \(\Omega(1/\epsilon^2)\) (under the optimal parameters that correspond to \(\Omega(n\sqrt{\beta} / \epsilon)\) lower bound). The \((1 \pm \epsilon)\) cut sketch then introduces an additive error of \(\Omega(1/\epsilon)\), which is much larger than \(\Theta(1)\), making it difficult to distinguish the values of \(s_i = \{-1, 1\}\). To overcome this, we instead encode \(1/\epsilon^2\) bits of information across \(1/\epsilon^2\) edges at the same time. When we want to decode a specific bit \(s_i\), we query the (directed) cut values between two carefully selected subsets \(A \in L_i\) and \(B \in R_j\). The key idea in our construction is that, even though each edge in \(A \times B\) encodes multiple bits of \(s\), the encoding of different bits of \(s\) remains minimally correlated : encoding other bits does influence the total weight from \(A\) to \(B\), but this effect is akin to adding noise, which only causes a small fluctuation in the total weight from \(A\) to \(B\).

This construction is based on the following technical lemma.

Lemma 2. For any integer \(k \ge 1\), there exists a matrix \(M \in \{-1, 1\}^{(2^k - 1)^2 \times 2^{2k}}\) such that: (1) \(\langle M_t, \mathbf{1} \rangle = 0 \) for all \(t \in [(2^k - 1)^2]\). (2) \(\langle M_t, M_{t’}\rangle = 0\) for all \(1 \le t < t’ \le (2^k - 1)^2\). (3) For all \(t \in [(2^k - 1)^2]\), the \(t\)-th row of \(M\) can be written as \(M_t = u \otimes v\) where \(u, v \in \{-1, 1\}^{2^k}\) and \(\langle u, \mathbf{1} \rangle = \langle v, \mathbf{1}\rangle = 0\).

Proof of Lemma 2

Our construction is based on the Hadamard matrix \(H = H_{2^k} \in \{-1, 1\}^{2^k \times 2^k}\). Recall that the first row of \(H\) is the all-ones vector and that \(\langle H_i, H_j \rangle = 0\) for all \(i \ne j\). For every \(2 \le i, j \le 2^k\), we add \(H_i \otimes H_j \in \{-1, 1\}^{2^{2k}}\) as a row of \(M\), so \(M\) has \((2^k - 1)^2\) rows.

Condition (3) holds because \(\langle H_i, \mathbf{1} \rangle = \langle H_j, \mathbf{1} \rangle = 0\) for all \(i, j \ge 2\). For Conditions (1) and (2), note that for any vectors \(u, v, w\), and \(z\), we have \(\langle u\otimes v, w \otimes z \rangle= \langle u, w \rangle \langle v, z \rangle \). Using this fact, Condition (1) holds because \(\langle M_t, \mathbf{1} \rangle = \langle H_i \otimes H_j, \mathbf{1} \otimes \mathbf{1} \rangle = \langle H_i, \mathbf{1} \rangle \langle H_j, \mathbf{1} \rangle = 0\), and Condition (2) holds because \((i,j) \neq (i’,j’)\) and thus \(\langle M_t, M_{t’} \rangle = \langle H_i \otimes H_j, H_{i’} \otimes H_{j’} \rangle = \langle H_{i}, H_{i’}\rangle \langle H_{j}, H_{j’}\rangle = 0 \). \(\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \square\)

We first prove a lower bound for the special case \(n = \Theta(\sqrt{\beta}/\epsilon)\). Our proof for this special case introduces important building blocks for proving the general case \(n = \Omega(\sqrt{\beta}/\epsilon)\).

Lemma 3. Suppose \(n = \Theta(\sqrt{\beta}/\epsilon)\). Any \((1 \pm \epsilon)\) for-each cut sketching algorithm for \(\beta\)-balanced \(n\)-node graphs must output \(\tilde{\Omega}(n \sqrt{\beta}/ \epsilon) = \tilde{\Omega}(\beta/ \epsilon^2)\) bits.

At a high level, we reduce the Index problem (Lemma 1) to the for-each cut sketching problem.

Given Alice’s string \(s\), we construct a graph \(G\) to encode \(s\), such that Bob can recover any single bit in \(s\) by querying \(O(1)\) cut values of \(G\). Our lower bound (Lemma 3) then follows from the communication complexity lower bound of the Index problem (Lemma 1), because Alice can run a for-each cut sketching algorithm and send the cut sketch to Bob, and Bob can successfully recover the \(O(1)\) cut values with high constant probability from the cut sketch.

Proof of Lemma 3.

We reduce from the Index problem. Let \(s \in \{-1, 1\}^{\beta(\frac{1}{\epsilon}-1)^2}\) denote Alice’s random string.

Construction of \(G\). We construct a directed complete bipartite graph \(G\) to encode \(s\). Let \(L\) and \(R\) denote the left and right nodes of \(G\), where \(|L| = |R| = \sqrt{\beta}/\epsilon\). We partition \(L\) into \(\sqrt{\beta}\) disjoint blocks \(L_1, \ldots, L_{\sqrt{\beta}}\) of equal size, and similarly partition \(R\) into \(R_1, \ldots, R_{\sqrt{\beta}}\). We divide \(s\) into \(\beta\) disjoint strings \(s_{i,j} \in \{-1, 1\}^{(\frac{1}{\epsilon}-1)^2}\) of the same length. We will encode \(s_{i,j}\) using the edges from \(L_i\) to \(R_j\). Note that the encoding of each \(s_{i,j}\) is independent since \(E(L_i, R_j) \cap E(L_{i’}, R_{j’}) = \varnothing\) for \((i, j) \neq (i’, j’)\).

We fix \(i\) and \(j\) and focus on the encoding of \(s_{i,j}\). Note that \(|L_i| = |R_j| = 1/\epsilon\). We refer to the edges from \(L_i\) to \(R_j\) as forward edges and the edges from \(R_j\) to \(L_i\) as backward edges. Let \(w \in \mathbb{R}^{1/\epsilon^2}\) denote the weights of the forward edges, which we will choose soon. Every backward edge has weight \(1/\beta\).

Let \(z = s_{i,j} \in \{-1, 1\}^{(\frac{1}{\epsilon}-1)^2}\). Assume w.l.o.g. that \(1/\epsilon = 2^t\) for some integer \(t\). Consider the vector \(x = \sum_{t=1}^{(\frac{1}{\epsilon}-1)^2} z_t M_t \in \mathbb{R}^{1/\epsilon^2}\) where \(M\) is the matrix in Lemma 2 with \(2^k = 1/\epsilon\). Because \(z_t \in \{-1, 1\}\) is uniformly random, each coordinate of \(x\) is a sum of \(O(1/\epsilon^2)\) i.i.d. random variables of value \(\pm 1\). By the Chernoff bound and the union bound, we know that with probability at least \(99/100\), \(|x|_{\infty} \le c_1 \ln(1/\epsilon)/\epsilon\) for some constant \(c_1 > 0\). If this happens, we set \(w = \epsilon x + 2 c_1 \ln(1/\epsilon) \mathbf{1}\), so that each entry of \(w\) is between \(c_1 \ln(1/\epsilon)\) and \(3 c_1 \ln(1/\epsilon)\). Otherwise, we set \(w = 2 c_1 \ln(1/\epsilon) \mathbf{1}\) to indicate that the encoding failed.

We first verify that \(G\) is \(O(\beta \log(1/\epsilon))\)-balanced. This is because every edge has a reverse edge with similar weight: For every \(u \in L\) and \(v \in R\), the edge \((u, v)\) has weight \(\Theta(\log(1/\epsilon))\), while the edge \((v, u)\) has weight \(1/\beta\).

Recovering a Bit in \(s\) from a For-Each Cut Sketch of \(G\) . Suppose Bob wants to recover a specific bit of \(s\), which belongs to the substring \(z = s_{i,j}\) and has an index \(t\) in \(z\). We assume that \(z\) is successfully encoded by the subgraph between \(L_i\) and \(R_j\).

For simplicity, we index the nodes in \(L_i\) as \(1, \ldots, (1/\epsilon)\) and similarly for \(R_j\). We index the forward edges \((u, v)\) in alphabetical order, first by \(u \in L_i\) and then by \(v \in R_j\). Under this notation, \(\langle w, \mathbf{1}_{A} \otimes \mathbf{1}_{B} \rangle\) gives the total weight \(w(A, B)\) of forward edges from \(A\) to \(B\), where \(\mathbf{1}_{A}, \mathbf{1}_{B} \in \{0,1\}^{1/\epsilon}\) are the indicator vectors of \(A \subset L_i\) and \(B \subset R_j\).The crucial observation is that, given a cut sketch of \(G\), Bob can approximate \(\langle w, M_t\rangle\) using \(4\) cut queries. By Lemma 2, \(M_t = h_A \otimes h_B\) for some \(h_A, h_B \in \{-1, 1\}^{1/\epsilon}\). Let \(A \subset L_i\) be the set of nodes \(u \in L_i\) with \(h_A(u) = 1\). Let \(B \subset R_i\) be the set of nodes \(v \in R_j\) with \(h_B(v) = 1\). Let \(\bar{A} = L_i \setminus A\) and \(\bar{B} = R_j \setminus B\).

\[ \langle w, M_t\rangle = \langle w, h_A \otimes h_B\rangle = \langle w, (\mathbf{1}_{A} - \mathbf{1}_{\bar{A}}) \otimes (\mathbf{1}_{B} - \mathbf{1}_{\bar{B}})\rangle = w(A, B) - w(\bar{A}, B) - w(A, \bar{B}) + w(\bar{A}, \bar{B}) \]

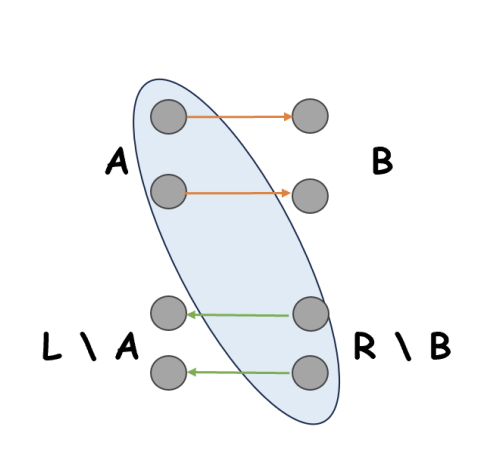

To approximate the value of \(w(A, B)\) (and similarly \(w(\bar{A}, B)\), \(w(A, \bar{B})\), \(w(\bar{A}, \bar{B})\)), Bob can query \(w(S, V \setminus S)\) for \(S = A \cup (R \setminus B)\). The edges from \(S\) to \(V \setminus S\) consist of forward edges from \(A\) to \(B\) and backward edges from \(R \setminus B\) to \(L \setminus A\). See Figure 2 as an example.

Figure 2: For \(S = A \cup(R \setminus B)\), the (directed) edges from \(S\) to \( V \setminus S \) consist of the following: the forward edges from \(A\) to \(B\), each with weight \(\Theta(\log(1/\epsilon))\), and the backward edges from \(R \setminus B\) to \(L \setminus A\), each with weight \(1/\beta\).

Figure 2: For \(S = A \cup(R \setminus B)\), the (directed) edges from \(S\) to \( V \setminus S \) consist of the following: the forward edges from \(A\) to \(B\), each with weight \(\Theta(\log(1/\epsilon))\), and the backward edges from \(R \setminus B\) to \(L \setminus A\), each with weight \(1/\beta\).

By Lemma 2, \(\langle h_A, \mathbf{1}\rangle = \langle h_B, \mathbf{1}\rangle = 0\), so \(|A| = |B| = \frac{|L_i|}{2} = \frac{|R_j|}{2} = \frac{1}{2\epsilon}\). The total weight of the forward edges is \(\Theta(\log(1/\epsilon) / \epsilon^2)\), and the total weight of the backward edges is \(\bigl(\frac{\sqrt{\beta}}{\epsilon}-\frac{1}{2\epsilon}\bigr)^2\frac{1}{\beta} = \Theta(1/\epsilon^2)\), so the cut value \(w(S, V \setminus S)\) is \(\Theta(\log(1/\epsilon)/\epsilon^2)\). Given a \((1 \pm \frac{c_2 \epsilon}{\ln(1/\epsilon)})\) for-each cut sketch, Bob can obtain a \((1 \pm \frac{c_2\epsilon}{\log(1/\epsilon)})\) multiplicative approximation of \(w(S, V \setminus S)\), which has \(O(c_2/\epsilon)\) additive error. After subtracting the total weight of backward edges, which is fixed, Bob has an estimate of \(w(A, B)\) with \(O(c_2/\epsilon)\) additive error. Consequently, Bob can approximate \(\langle w, M_t\rangle\) with \(O(c_2/\epsilon)\) additive error using \(4\) cut queries.

Now consider \(\langle w, M_t\rangle\). By Lemma 2, \(\langle M_t, \mathbf{1}\rangle = 0\) and the rows of \(M\) are orthogonal:

\[ \langle w, M_t\rangle = \langle \epsilon x, M_t\rangle = \epsilon \langle \sum_{t’} z_{t’} M_{t’}, M_t\rangle = \epsilon \left(\sum_{t’} z_{t’} \langle M_t, M_{t’}\rangle\right) = \epsilon z_t |M_t|_2^2 = \frac{z_t}{\epsilon} \]

We can see that, for a sufficiently small universal constant \(c_2\), Bob can distinguish whether \(z_t = 1\) or \(z_t = -1\) based on an \(O(c_2/\epsilon)\) additive approximation of \(\langle w, M_t\rangle\). Bob’s success probability is at least \(0.95\), because the encoding of \(z\) fails with probability at most \(0.01\), and each of the \(4\) cut queries fails with probability at most \(0.01\). (Note that the success probability of a cut query given a for-each cut sketch (Definition 1) can be boosted from \(2/3\) to \(99/100\), e.g., by running the sketching and recovering algorithms \(O(1)\) times and taking the median. This increases the length of Alice’s message by a constant factor, which does not affect our asymptotic lower bound.) \(\ \ \square\)

We next consider the case with general values of \(n\), \(\beta\), and \(\epsilon\), and prove Theorem 1.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Let \(k = \sqrt{\beta} / \epsilon\). We assume w.l.o.g. that \(k\) is an integer, \(n\) is a multiple of \(k\), and \((1/\epsilon)\) is a power of \(2\). Suppose Alice has a random string \(s \in \{-1, 1\}^{\Omega(nk)}\). We will show that \(s\) can be encoded into a graph \(G\) such that:

- \(G\) has \(n\) nodes and is \(O(\beta \log(1/\epsilon))\)-balanced, and

- Given a \((1 \pm \frac{c_2\epsilon} {\ln(1/\epsilon)})\) for-each cut sketch of \(G\) and an index \(q\), where \(c_2 > 0\) is a sufficiently small universal constant, Bob can recover \(s_q\) with probability at least \(2/3\).

Consequently, by Lemma 1, any for-each cut sketching algorithm must output \(\Omega(nk) = \Omega(n \sqrt{\beta}/\epsilon) = \tilde{\Omega}(n \sqrt{\beta’}/\epsilon’)\) bits for \(\beta’ = O(\beta \log(1/\epsilon))\) and \(\epsilon’ = c_2 \epsilon / \ln(1/\epsilon)\).

We first describe the construction of \(G\). We partition the \(n\) nodes into \(\ell = n / k \ge 2\) disjoint sets \(V_1, \ldots, V_\ell\), each containing \(k\) nodes. Let \(s\) be Alice’s random string with length \(\beta (\frac{1}{\epsilon} - 1)^2 (\ell-1) = \Omega(k^2 \ell)= \Omega(nk)\). We partition \(s\) into \((\ell - 1)\) strings \((s_i)_{i=1}^{\ell - 1}\), with \(k^2\) bits in each substring. We then follow the same procedure as in Lemma 3 to encode \(s_i\) into a complete bipartite graph between \(V_i\) and \(V_{i+1}\). Notice that we have \(|s_i| = \beta (\frac{1}{\epsilon} - 1)^2 \) and \(|V_i| = |V_{i+1}| = \sqrt{\beta}/\epsilon\), which is the same setting as in Lemma 3.

We can verify that \(G\) is \(O(\beta\log(1/\epsilon))\)-balanced. This is because every edge \(e\) has a reverse edge whose weight is at most \(O(\beta\log(1/\epsilon))\) times the weight of \(e\). For every \(u \in V_i\) and \(v \in V_{i+1}\), the edge \((u, v)\) has weight \(\Theta(\log(1/\epsilon))\), while the edge \((v, u)\) has weight \(1/\beta\).

We next show that Bob can recover the \(q\)-th bit of \(s\). Suppose Bob’s index \(q\) belongs to the substring \(s_i\) which is encoded by the subgraph between \(V_{i}\) and \(V_{i+1}\). Similar to the proof of Lemma 3, Bob only needs to approximate \(w(A, B)\) for \(4\) pairs of \((A, B)\) with \(O(1/\epsilon)\) additive error, where \(A \subset V_i\), \(B \subset V_{i+1}\), and \(|A| = |B| = \frac{1}{2\epsilon}\). To achieve this, Bob can query the cut value \(w(S, V \setminus S)\) for \(S = A \cup \left(V_{i + 1} \setminus B\right) \bigcup_{j = i + 2}^{\ell} V_j\). The edges from \(S\) to \((V \setminus S)\) are:

- \(\frac{1}{4\epsilon^2}\) forward edges from \(A\) to \(B\), each with weight \(\Theta(\log(1/\epsilon))\).

- \(\bigl(\frac{\sqrt{\beta}}{\epsilon}-\frac{1}{2\epsilon}\bigr)^2\) backward edges from \((V_{i+1} \setminus B)\) to \((V_{i} \setminus A)\), each with weight \(\frac{1}{\beta}\).

- \(\frac{\sqrt{\beta}}{2\epsilon^2}\) backward edges from \(A\) to \(V_{i - 1}\) when \(i \ge 2\), each with weight \(\frac{1}{\beta}\).

The cut value \(w(S, V \setminus S)\) is \(\Theta(\log(1/\epsilon)/\epsilon^2)\). Consequently, given a \((1 \pm \frac{c_2\epsilon} {\ln(1/\epsilon)})\) for-each cut sketch, after subtracting the fixed weight of the backward edges, Bob can approximate \(w(A, B)\) with \(O(c_2/\epsilon)\) additive error. Similar to the proof of Lemma 3, for sufficiently small constant \(c_2 > 0\), repeating this process for \(4\) different pairs of \((A, B)\) will allow Bob to recover \(s_q \in \{-1, 1\}\). \(\square\)

References

[Benczúr and Karger, 1996]: András A. Benczúr and David R. Karger. Approximating s-t minimum cuts in \(\tilde{O}(n^2)\) time. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on the Theory of Computing (STOC), pages 47–55, 1996

[Spielman and Teng, 2011]: Daniel A. Spielman and Shang-Hua Teng. Spectral sparsification of graphs. SIAM J.Comput., 40(4):981–1025, 2011.

[BSS, 2012]: Joshua D. Batson, Daniel A. Spielman, and Nikhil Srivastava. Twice-Ramanujan sparsifiers. SIAM J. Comput., 41(6):1704–1721, 2012.

[ACK+, 2016]: Alexandr Andoni, Jiecao Chen, Robert Krauthgamer, Bo Qin, David P. Woodruff, and in Zhang. On sketching quadratic forms. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science (ITCS), pages 311–319, 2016.

[EMPS, 2016]: Alina Ene, Gary L. Miller, Jakub Pachocki, and Aaron Sidford. Routing under balance. In Proceedings of the 48th Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC), pages 598–611, 2016.

[IT, 2018]: Motoki Ikeda and Shin-ichi Tanigawa. Cut sparsifiers for balanced digraphs. In Approximation and Online Algorithms - 16th International Workshop (WAOA), volume 11312 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 277–294, 2018.

[CCPS, 2021]:Ruoxu Cen, Yu Cheng, Debmalya Panigrahi, and Kevin Sun. Sparsification of directed graphs via cut balance. In 48th International Colloquium on Automata, Languages, and Programming (ICALP), volume 198 of LIPIcs, pages 45:1–45:21, 2021.