Integrating Static and Data-Driven Resource Analyses for Programs

Resource analysis of programs aims to infer their worst-case cost bounds. It has a number of practical use cases. For example, when executing a client’s program in cloud computing, a cloud-service provider (e.g., Amazon Web Services or Microsoft Azure) would like to to avoid both over-provisioning resources (which would reduce profits) and under-provisioning resources (which would violate the service-level agreement). So the provider would like to to estimate the resource usage of the client’s program in advance, thereby optimizing resource allocation.

There are two approaches to resource analysis: static analysis and data-driven analysis . Static analysis infers a cost bound by examining the source code and reasoning about all theoretically possible behaviors of a program, including its worst-case behavior. Data-driven analysis first runs the program on many inputs and records the execution costs. It then analyzes the cost measurements to infer a cost bound.

Static and data-driven analyses have complementary strengths and weaknesses. Static analysis is sound : if it returns some candidate cost bound, it is guaranteed to be a valid upper bound on the actual execution cost. However, resource analysis for a Turing-complete language is generally undecidable. Consequently, static analysis is incomplete : no matter how clever the static analysis is, there always exists a program that the static analysis cannot handle. In contrast to static analysis, data-driven analysis can infer a cost bound for any program. However, because data-driven analysis cannot rigorously reason about the program’s worst-case behavior, data-driven analysis offers no soundness guarantees of its inferred cost bounds.

In this blog post, we describe how to integrate static and data-driven resource analyses into hybrid resource analysis . By combining the two complementary analysis techniques, hybrid resource analysis partially retains their respective strengths while mitigating their weaknesses. We first introduce static resource analysis, followed by data-driven resource analysis. We then describe hybrid resource analysis and demonstrate its advantages over static and data-driven analyses using an example of a linear-time selection algorithm.

Formulation of Resource Analysis

Given a program , the goal of resource analysis is to infer its worst-case cost bound. Concretely, it is a function parametric in an input (or its size ) to the program such that, for any input , the value is a correct upper bound of the execution cost of . The execution cost of the program is defined by a resource metric such as running time, memory, or energy.

To specify a resource metric of interest, a user inserts an instruction

tick q

throughout their code, where

q

is a (positive or negative) number. The

instruction indicates that

q

many resources are consumed. For example, if we

are interested in the amount of memory (in bits) consumed by a program, whenever

a 64-bit memory cell is allocated in the source code, we indicate it by

inserting an instruction

tick 64

.

Static Analysis

To automate resource analysis, static resource analysis automatically analyzes the source code of a program. In this blog post, we focus on Automatic Amortized Resource Analysis (AARA) as a concrete example of state-of-the-art static resource analysis. Taking as input a functional program , AARA tries to automatically infer a polynomial cost bound of the program .

AARA

AARA builds on the potential method from

amortized

analysis

. Every data structure

during program execution is equipped with

potential

, which we can consider as

fuel for computation. To perform computation, data structures must come with

enough potential to pay for the cost of computation. For example, if we are to

run an instruction

tick 64

, we must have at least 64 units of potential

available. The remaining potential can be later used to pay for subsequent

computation. In the potential method, our goal is to figure out an appropriate

amount of potential to store in data structures such that, whenever they go

through computation, they have enough potential to pay for it. The overall cost

is then bounded above by the initial potential minus the final potential stored

in the data structures. So the difference between the initial and final

potential serves as a cost bound.

AARA uses types to express the amount of potential stored in data structures. For illustration, consider a variable of the integer-list type . If we want the list to come with one unit of potential per list element, we write where the superscript 1 indicates the amount of potential stored in each list element. The type is called a resource-annotated type , and the superscript 1 is called a resource annotation .

Let’s look at a slightly more complicated example. Consider function

split

that splits an input list into two equal halves. The function traverses

the input and processes each list element. If the cost of processing

each element is one, the total computational cost is equal to the input list

length . We express the resource usage of the function

split

by

On the left-hand side of the turnstile (i.e., ), we have , which means the input carries one unit of

potential per element. On the right-hand side of the turnstile, we have

,

which means the two output lists of function

split

each carry zero units of

potential per element. This assignment of potential makes sense. In the input

list , each element initially carries one unit of potential. This

potential is used to pay for the cost of function

split

, and the

remaining zero units of potential are stored in the two output lists after

splitting. The difference between the input potential (i.e., ) and output potential (i.e., zero) immediately translates to the cost

bound of function

split

.

Although the function

split

stores zero potential in the output, we will need

a positive amount of potential in the output if it later undergoes computation

that demands potential. In such a case, we can increase the potential stored in

the input and output of the function

split

. For example, another valid

assignment of potential is

where the input carries three units of potential per list element and the output

carries two unit of potential, which can be used to pay for subsequent

computation.

Given a program , how do we infer its resource-annotated type? First, we assign numeric variables to all inputs and outputs that appear in ’s source code. These variables stand for (yet-to-be-determined) resource annotations, which encode the amounts of potential. For example, in the program , the input and output of the whole program are assigned variables :

We then walk through the source code, collecting linear constraints that relate

the variables assigned to the inputs and outputs. For example, if the program

contains instruction

tick 64

, AARA’s type system imposes a linear

constraint that the input potential must be at least 64 plus the leftover

potential after running

tick 64

. In the example of ,

we obtain two linear constraints

Finally, we solve the linear constraints using a linear-program (LP) solver. If we obtain a solution, we can extract a resource-annotated type of the program .

Incompleteness

The static resource analysis technique AARA is sound but incomplete. Soundness means that, if AARA returns a candidate cost bound, it is guaranteed to be a valid worst-case cost bound. However, AARA is incomplete: even if a program has a polynomial cost bound, AARA can fail to infer it. This happens when the linear constraints collected during type inference are unsolvable. In fact, this limitation is not unique to AARA. All static resource analysis techniques suffer incompleteness because resource analysis is undecidable in general.

To illustrate AARA’s incompleteness, let us consider the median-of-medians-based linear-time selection algorithm. Given an input list and an input integer , the selection algorithm returns the -th smallest element in the list .

In this algorithm, we split input list into blocks of five elements and compute each block’s median (e.g., by brute force). We then recursively call the algorithm on these medians to compute their median . The median of medians (hence the name of the algorithm) is used to partition the input list into two lists, and . To prove the linear time complexity of this algorithm, we must show that the sublists and are each at most of the list . Intuitively, the median of medians partitions the list evenly (up to some factor) even in the worst case.

However, AARA cannot reason about the mathematical properties of medians. As a result, it cannot conclude that the median of medians splits the list evenly. Instead, AARA deduces that, in the worst case, the list is split unevenly into a singleton list (i.e., containing only one element) and the remaining sublist. If the list were split this way, the worst-case time complexity would be exponential. Hence, AARA is unable to infer a polynomial cost bound for this algorithm even though it has a linear cost bound. Furthermore, we are not aware of static analysis techniques that can correctly infer linear cost bounds for the linear-time selection algorithm.

Data-Driven Analysis

The second approach to automatic resource analysis is data-driven resource analysis . It starts with collecting cost measurements of the program . Given inputs , we run for each and record its output and execution cost . This yields a runtime cost dataset defined as The dataset records output as well as input since we need to know output sizes to calculate a cost bound (i.e., the difference between the input and output potential). We then infer a cost bound of the program by analyzing the dataset . We have a variety of choices for data-analysis techniques, ranging from linear regression to deep learning.

Bayesian Resource Analysis

This blog post introduces Bayesian resource analysis , where we apply Bayesian inference to resource analysis. In abstract, the goal of Bayesian inference is to infer latent variables (i.e., variables that we want to know but cannot observe) from observed variables (i.e., variables whose concrete values are available) using Bayes’ rule from probability theory. In Bayesian resource analysis, latent variables are resource annotations (i.e., cost bounds), and observed variables are the runtime cost dataset of the program.

To conduct Bayesian resource analysis, the user first provides a probabilistic model , which specifies a joint probability distribution of resource annotations and dataset . Next, by Bayes’ rule, the posterior distribution of the cost bound conditioned on a concrete dataset is given by This equation suggests that we can compute the posterior distribution by taking the ratio between the joint distribution and the denominator . However, because the denominator is an integral over the space of the resource annotations , which may have many dimensions, it is often intractable to compute the denominator. As a result, we cannot precisely compute the posterior distribution by directly applying Bayes’ rule.

Instead, in practice, we run a sampling-based Bayesian inference algorithm, drawing a large number of samples from the posterior distribution. We then use these samples, which serve as an approximation of the posterior distribution, to estimate various properties (e.g., mean, median, variance, etc.) of the posterior distribution.

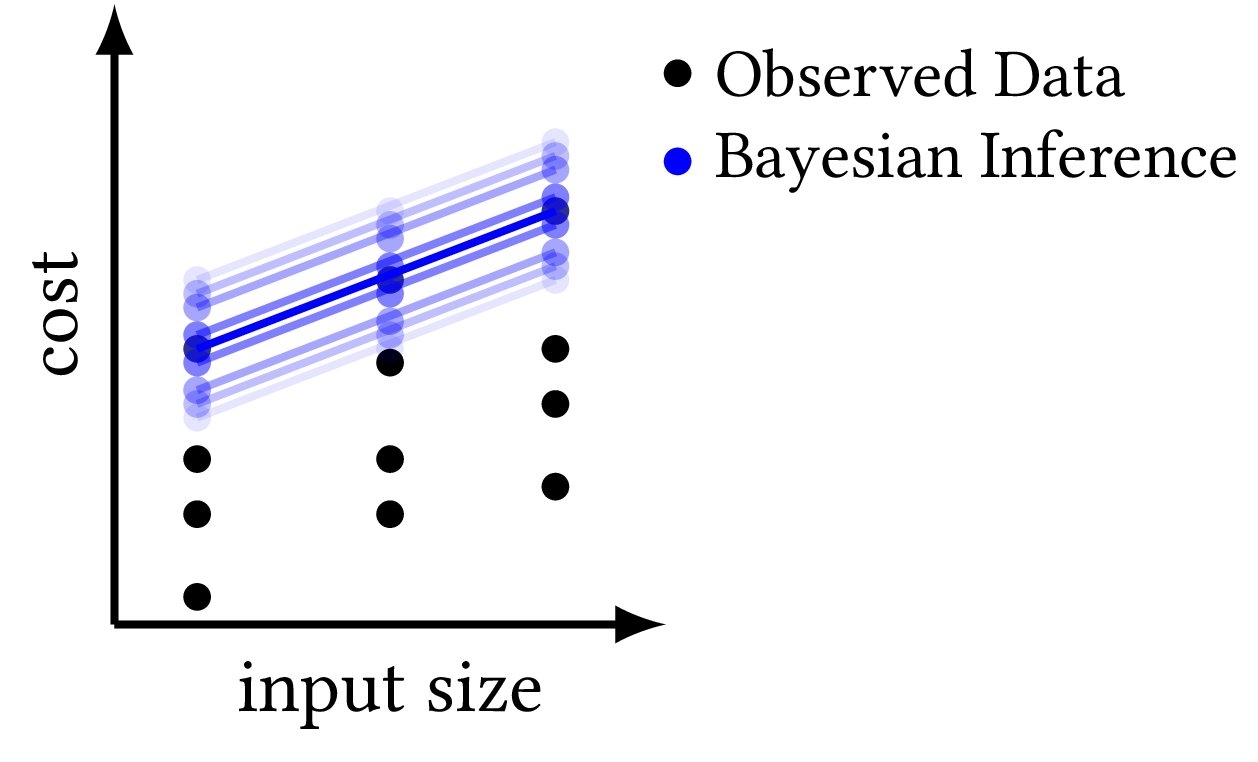

Figure 1 displays a schematic diagram of Bayesian resource analysis. We perform Bayesian inference to infer a posterior distribution of cost bounds (blue lines) from the runtime cost measurements (black dots).

To illustrate Bayesian resource analysis, consider the function

split

that was

introduced

earlier

. Its resource-annotated type has the form

where the resource annotations are

to be inferred by Bayesian inference.

Let a dataset of runtime cost measurements be where is an input list, is a pair of two output lists, and is the cost of running .

The user constructs a probabilistic model based on whatever

domain knowledge

1

they have. For example, a probabilistic

model for

split

can be

The first line states that the resource annotations follow a

normal distribution truncated to the non-negative region. In the second line,

the predicted costs are defined as ,

which is the difference between input and output potential. The third line

states that the observed costs from the dataset

follow a normal distribution truncated to the interval . The distribution is truncated because the prediction of a

worst-case

cost bound must be larger than or equal to the observed cost.

Unsoundness

Data-driven analysis can infer a cost bound for any program , provided that it terminates. When we construct a dataset of the program ’s runtime cost measurements, the program must terminate on all inputs; otherwise, we will never finish collecting runtime cost measurements. Once we finish data collection, we statistically infer a polynomial cost bound from the dataset . As the dataset is finite, for any degree , we always have some degree- polynomial bound that lies above all runtime cost measurements of . Therefore, data-driven analysis always returns an inference result.

However, data-driven analysis lacks the soundness guarantee 2 of inference results. Data-driven analysis examines runtime cost data of the input program , rather than its source code. Consequently, data-driven analysis cannot reason about the theoretically worst-case behavior of the program , failing to provide a soundness guarantee.

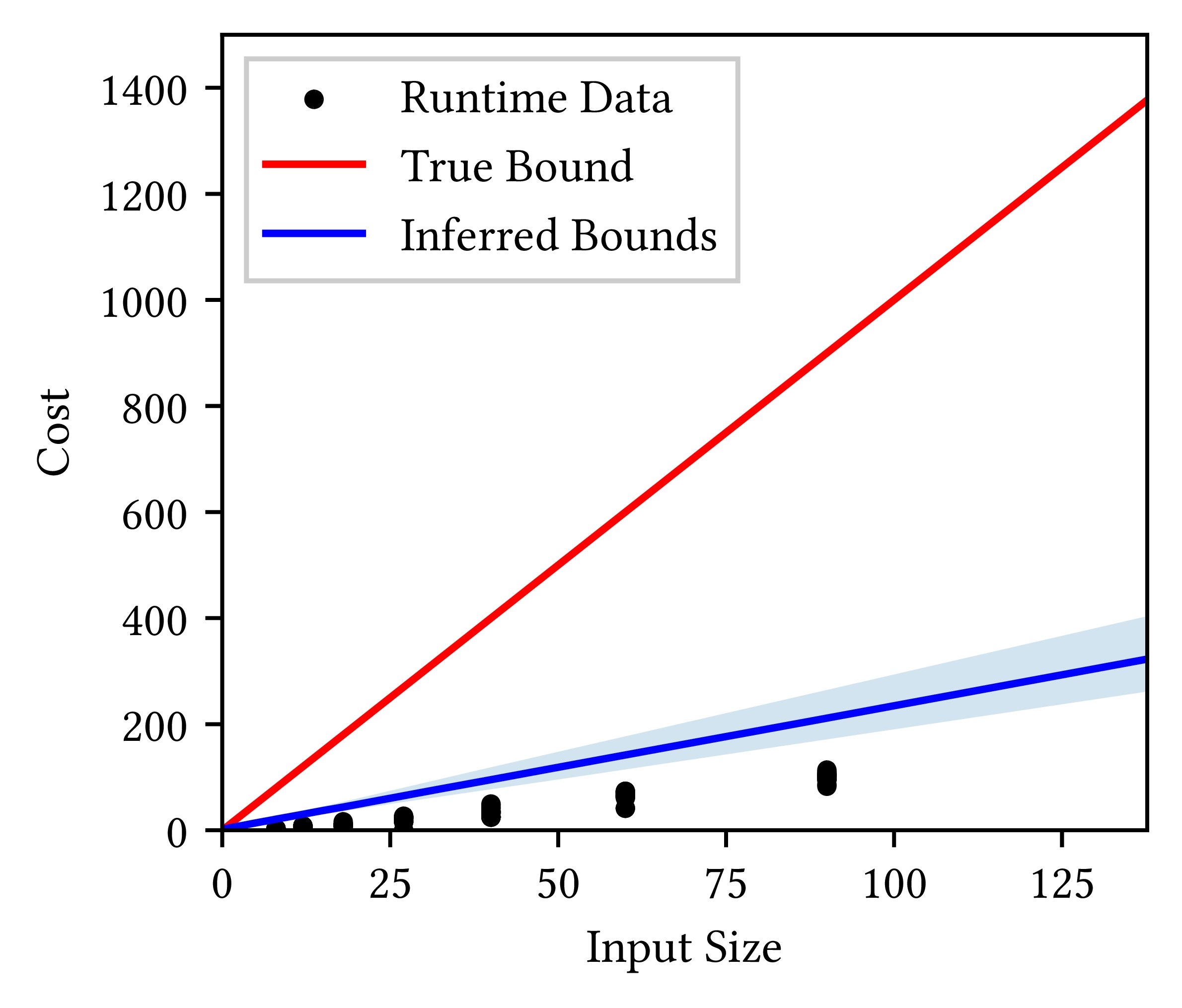

For illustration, we ran Bayesian resource analysis on the median-of-medians-based linear-time selection algorithm. To collect cost measurements, we randomly generated input lists. Figure 2 plots the inferred posterior distribution of cost bounds. Black dots are runtime cost measurements. The light-blue shade is the 10-90th percentile range of the posterior distribution, and the blue line is the median cost bound. The red line is the true worst-case cost bound.

Although the inferred cost bounds (light-blue shade) all lie above the observed costs (black dots), they are unsound worst-case cost bounds since they lie below the true worst-case cost bound (red line). The true cost bound (red line) is significantly larger than observed costs (black dots) because, when inputs are randomly generated, the worst-case behavior of the selection algorithm rarely arises.

Certainly, we can fix this problem by adjusting the probabilistic model such that it adds more buffer on top of the maximum observed costs in the dataset . However, it is difficult to tell a priori how much buffer we should add. On the other hand, static analysis is better suited for reasoning about the worst-case behavior than data-driven analysis. But if we perform static analysis on the entire source code of the linear-time selection algorithm, the analysis fails as described earlier . Can we perform static analysis on a fragment of the source code and data-driven analysis on the rest?

Hybrid Analysis

To overcome the limitations of purely static analysis (e.g., conventional AARA) and purely data-driven analysis (e.g., Bayesian resource analysis), we integrate them into a framework called hybrid AARA.

Hybrid AARA

First, a user indicates which part of the source code should be analyzed by

data-driven analysis. For example, if we want expression

e

to be analyzed by

data-driven analysis, we enclose

e

with the annotation

statistics

, resulting

in

statistics(e)

. The rest of the source code will be analyzed by static

analysis. To construct a dataset of runtime cost measurements,

we run the program on many inputs (to ) and record the inputs,

outputs, and costs of the expression

e

inside

statistics(e)

. Here, the input

to the expression

e

is its evaluation context (i.e., the values of free

variables appearing in

e

) during the program ’s execution.

The data-driven analysis of the expression

e

incorporates its contextual

information at runtime as the dataset captures this contextual

information. For example, suppose

statistics(e)

appears inside the if-branch

of a conditional expression

if ... then ... else ...

. If the if-branch

satisfies some invariant (e.g., inside the if-branch, variable

x

appearing

inside

e

is even), then all measurements recorded in the dataset

satisfy this invariant. Thus, data-driven analysis does not

analyze the expression

e

in isolation from its context.

Next, we infer a cost bound in hybrid AARA. Given a program containing

statistics(e)

for some expression

e

, we perform data-driven analysis on

e

and static analysis on the rest of the source code, and then combine their

inference results. Just like we did for the cost-bound inference of

conventional AARA

, we assign variables to inputs and outputs throughout

the source code of the program , where these variables stand for

yet-to-be-inferred resource annotations. In hybrid AARA, however, we do not

assign variables

inside

the expression

e

. That is, the expression

e

is

treated as a black box whose source code is invisible. Let be the

set of resource annotations in the input and output of the expression

statistics(e)

. Also, let be a set of all

variables in the program ’s entire source code.

A key challenge in hybrid AARA is the interface between conventional AARA and Bayesian resource analysis. Suppose conventional AARA generates a set of linear constraints over the variables . Any solution to the linear constraints is a valid cost bound. Conventional AARA optimizes the variables subject to the linear constraints . This optimization problem is solved by an LP solver. On the other hand, Bayesian resource analysis infers a posterior distribution of the variables by running a sampling-based Bayesian inference algorithm. Thus, conventional AARA and Bayesian resource analysis both involve the variables in common, but they each use different algorithms for inference. How do we design their interface?

One idea is to restrict the state space of the sampling algorithm to the feasible region of the linear constraints . We first construct a probabilistic model over all variables , which represent resource annotations in the program ’s source code. We then run a sampling-based Bayesian inference algorithm over these variables, subject to the linear constraints . Thanks to the constraints , any cost bound drawn from the posterior distribution is a valid cost bound according to conventional AARA.

To implement hybrid AARA, we rely on recent advances in the literature of sampling algorithms. In 2021, a C++ library volesti started to support sampling from a user-specified probability distribution subject to arbitrary linear constraints. This is the first (and so far, only) tool that supports such sampling. Popular programming languages for Bayesian inference, such as Stan , only support box constraints (i.e., upper and lower bounds) on random variables, but not arbitrary linear constraints that may involve multiple variables.

Evaluation

We ran Hybrid AARA on the linear-time selection algorithm. Inside the selection

algorithm’s source code, the code fragment

partition x m

, which partitions

list

x

around the median of medians

m

, is analyzed by data-driven analysis.

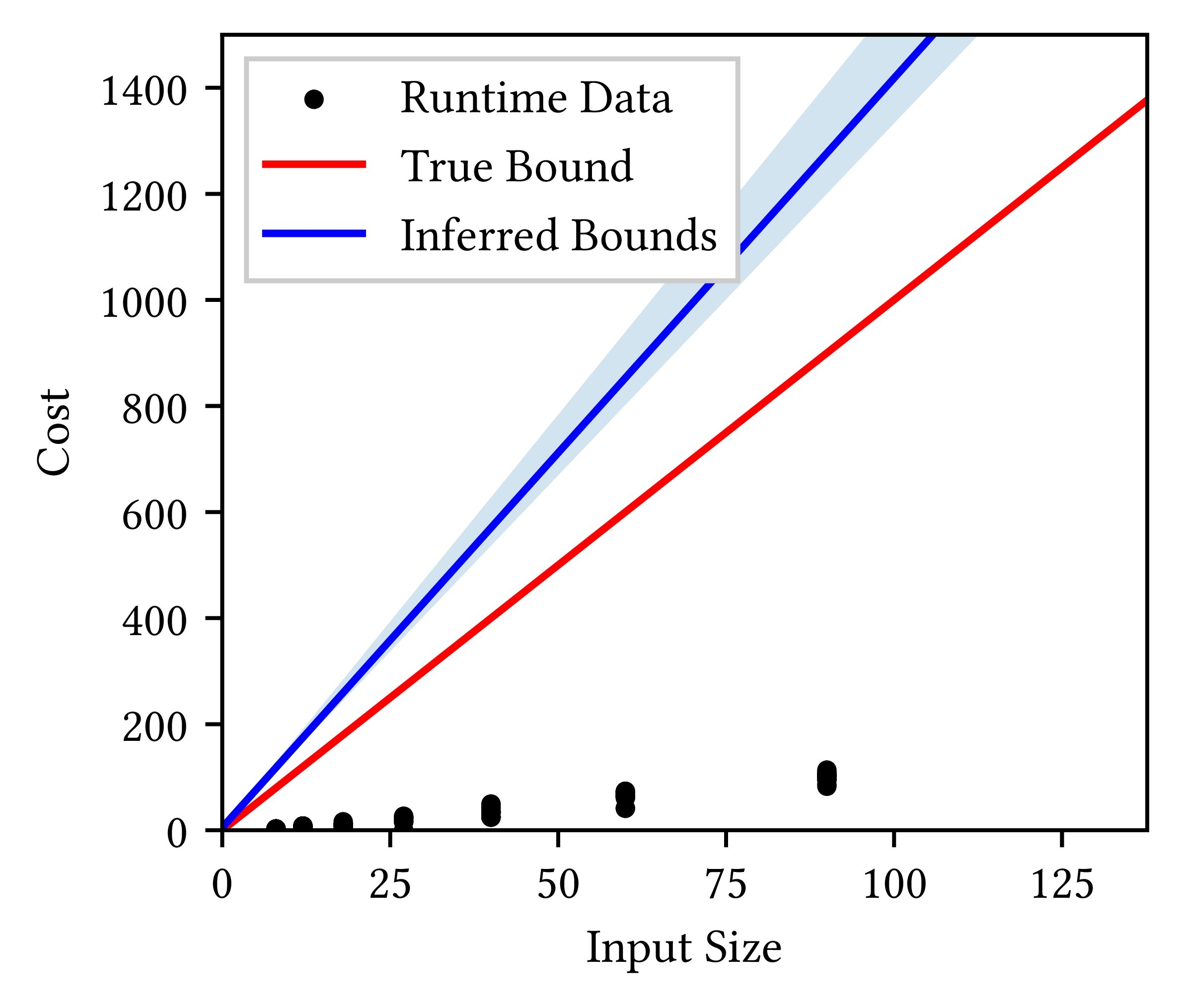

The rest of the source code is analyzed by static analysis. Figure 3 displays

the inference results.

In Figure 3, the 10-90th percentile ranges (light-blue shade) of inferred cost bounds now contain or lie above the ground truth (red line). This is a significant improvement over Bayesian resource analysis (Figure 2), where the inferred cost bounds are below the true worst-case bounds.

More generally, we have evaluated hybrid AARA on a suite of seven benchmarks:

MapAppend

,

Concat

,

InsertionSort2

,

QuickSort

,

QuickSelection

,

MedianOfMedians

(this is the linear-time selection algorithm we have seen in

this blog post), and

ZAlgorithm

. Conventional AARA fails in all benchmarks as

they each contain a code fragment that cannot be analyzed statically by

conventional AARA. Further, in all benchmarks, hybrid AARA infers cost bounds

closer to the true worst-case cost bounds than purely data-driven resource

analysis. Thus, our evaluation demonstrates the benefits of hybrid resource

analysis: hybrid analysis infers more accurate worst-case cost bounds than

purely data-driven analysis, while overcoming the incompleteness of purely

static analysis. The details of the evaluation can be found in out paper

Robust

Resource Bounds with Static Analysis and Bayesian Inference

.

Conclusion

Hybrid resource analysis combines purely static analysis, which offers soundness guarantees of worst-case cost bounds but is incomplete, and purely data-driven analysis, which is not sound but can infer a cost bound for any program. By combining these two complementary analysis techniques, hybrid resource analysis successfully infers cost bounds that neither purely static analysis nor purely data-driven analysis can infer. This is demonstrated by the experiment results of the linear-time selection algorithm.

Hybrid AARA has a limitation that its data-driven analysis only infers resource annotations, but not other quantities (e.g., depth of recursion). As a result, hybrid AARA cannot handle some programs such as bubble sort. In bubble sort, conventional AARA cannot infer the number of recursive calls, but it can still correctly infer a cost bound of each recursive call. Therefore, ideally, we would like to infer (i) the number of recursive calls by data-driven analysis and (ii) the cost of each recursive call by conventional AARA. This requires a different hybrid analysis technique from hybrid AARA presented in this blog post, and we plan to investigate it as future work.

Acknowledgement: hybrid AARA is joint work with Feras Saad and Jan Hoffmann . Our paper Robust Resource Bounds with Static Analysis and Bayesian Inference is currently under review, and hopefully we can share it soon.

Further reading: the original paper on AARA targets linear cost bounds. Subsequently, AARA has been extended to univariate polynomial cost bounds and multivariate polynomial cost bounds . Resource-aware ML is an implementation for AARA for analyzing OCaml programs. Papers on data-driven resource analysis include the trend profiler , algorithmic profiler , and input-sensitive profiler . They are all concerned with average-case cost bounds, rather than worst-case cost bounds as in this blog post. Also, these papers all use optimization instead of Bayesian inference.

In contrast to static analysis, data-driven analysis (including Bayesian resource analysis) always requires the user’s domain knowledge to construct a statistical model. This dependency on domain knowledge is inherent in statistics: the inference result depends on our choice of data-analysis methodologies (e.g., optimization or Bayesian inference), statistical models, and hyperparameters.

Here, by the lack of soundness guarantee, we mean that the cost bound inferred by data-driven analysis is not guaranteed to be a valid worst-case cost bound for all possible inputs to the program. Nonetheless, data-driven analysis is sound with respect to the probabilistic model and dataset used, as long as we use a correct inference algorithm.