Maximal Extractable Value in Ethereum

In 2008, a groundbreaking development in the world of finance occurred: the birth of Bitcoin, the first decentralized digital currency. This innovation, introduced by blockchain technology, enables value transfer between parties without the need for traditional intermediaries like banks.

Fast forward to 2015, the blockchain landscape evolved further, giving rise to decentralized finance (DeFi). This advancement allowed for a more complex financial ecosystem where various assets could be exchanged, used as collateral, and borrowed—all without centralized authorities. As the DeFi world flourished, new profit-making opportunities emerged, with one of the most intriguing being Maximal Extractable Value (MEV). In 2021, MEV generated an impressive $540M in profits over 32 months.

MEV represents a unique form of potential profit available to a specific group within blockchain networks. In Proof of Work systems, this group consists of miners, while in Proof of Stake systems, they’re known as block proposers. These participants have privileged access to unconfirmed transactions, allowing them to potentially extract risk-free profits.

This blog will explore the fascinating world of MEV through the following sections:

- Blockchain Fundamentals: We’ll start with a high-level, intuitive explanation of blockchain technology, providing the necessary context for understanding MEV.

- MEV in Action: We’ll examine several common MEV strategies, offering concrete examples of how these profits are harvested in practice.

- Deep Dive: Ethereum Consensus Mechanism: We’ll focus on the Ethereum ecosystem post-transition to Proof of Stake, explaining why MEV opportunities are primarily accessible to block proposers in this context.

- The MEV Dilemma: Finally, we’ll discuss the broader implications of MEV activities, including potential problems they pose for blockchain networks and current solutions.

What is a blockchain

A blockchain is a public ledger, similar to a digital notebook, that keeps track of transactions (e.g., sending money to someone). Imagine each page of the notebook is a block, and each block lists a bunch of these trades. Once a page is full, it gets added to the notebook, linking it to the previous page. This linking creates a chain of pages, or blocks, hence the name “blockchain.”

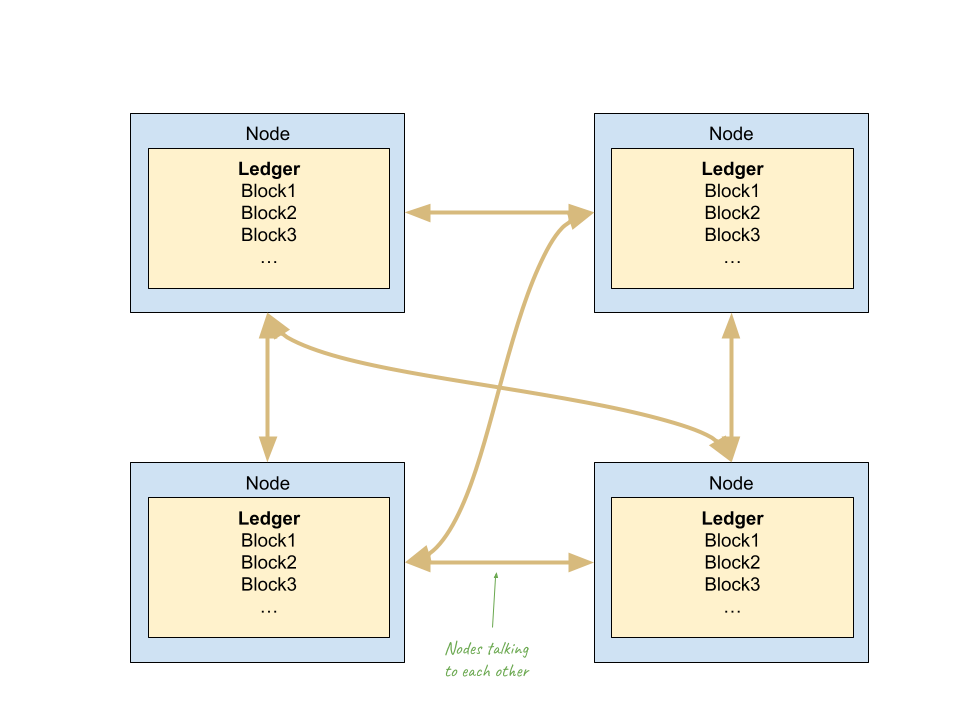

This public ledger is stored on multiple computers called “nodes,” which form a blockchain network. These nodes communicate with each other to maintain the integrity and consistency of the ledger. Figure 1 is an illustration of a blockchain network with four nodes.

Anyone can become a node, meaning they would have a full copy of the blockchain. To add a new transaction, you only need to interact with one node to make your transaction public in the blockchain network. The nodes then work together to group transactions into blocks and add them to the blockchain.

With this public ledger and cryptographic tools, values like Bitcoin(BTC), Ether(ETH), and USD Coin(USDC) can be recorded and owned. Additionally, some blockchains, like Ethereum, have the capability of running smart contracts, which are self-executing programs that automatically enforce and execute the code. These smart contracts operate on a Turing-complete machine, meaning they can perform any computation given enough resources. This allows blockchains to support complex financial services, such as exchanges, options, and lending, directly on the network.

To put it simply, think of a blockchain as a secure, decentralized ledger that records all transactions across a network of computers. This ledger is visible to everyone and can’t be easily changed.

Common MEV Examples

Numerous MEV opportunities abound within finance services (called Decentralized Finance protocols on the blockchain) mentioned above, particularly exchanges and lending platforms. MEV refers to the profit made by reordering, including, or excluding transactions when they are added to a block on the blockchain.

Let’s use a simplified model to help understand. Assume that there are only two players in the MEV ecosystem: ordinary users and MEV searchers. Ordinary users like you and me perform regular transactions, such as buying or selling cryptocurrencies. MEV searchers, on the other hand, are specialized actors who try to exploit the way transactions are ordered in a block to make a profit. These searchers can see ordinary users’ transactions before they are included in blocks.

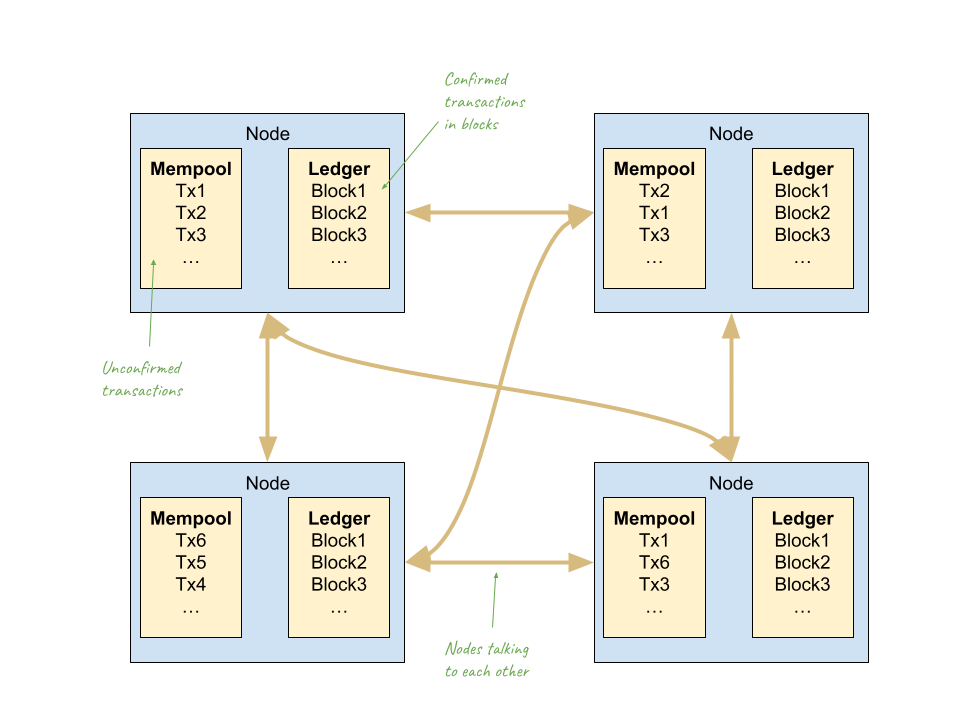

For example, an ordinary user wants to buy a cryptocurrency on a decentralized exchange. When they submit their transaction, it doesn’t get processed immediately; instead, it waits in a queue called the “mempool,” as shown in Figure 2. Each node’s mempool may differ because of network delays, and nodes could be connected to different ordinary users.

MEV searchers can monitor this mempool and see the transaction. If they notice an opportunity to profit by placing their own transaction before or after the user’s transaction, they will do so. This could involve placing a transaction just before the user’s transaction (to benefit from the price increase the user’s transaction will cause) and/or placing a transaction immediately after the user’s transaction (to benefit from the price increase the user’s transaction has caused already). Details are explained below.

Arbitrage

The first kind of MEV opportunities we introduce is arbitrage. Arbitrage happens in Decentralized exchanges (DEX) platforms when MEV searchers make a buying and a selling transactions right after an ordinary user’s transaction.

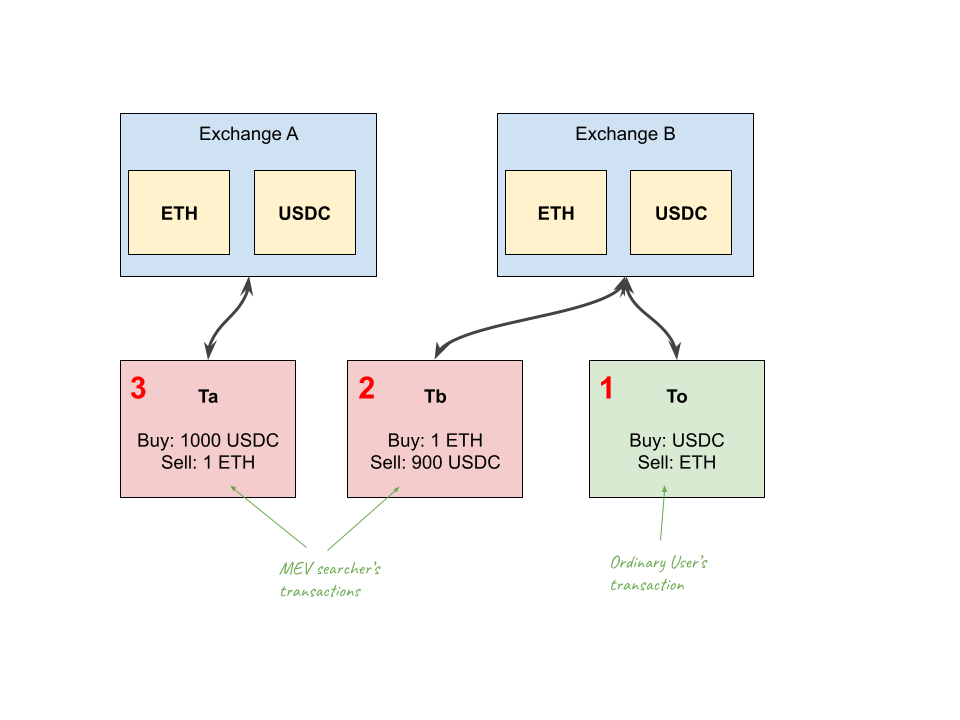

Decentralized exchanges (DEX) allow users to exchange between two kinds of tokens (e.g., ETH and USDC). However, if two exchanges are supporting the same pair of tokens and offer different prices, there are profits.

For example, the price for USDC/ETH is 1000 in both DEX A and Dex B. Right after an ordinary user exchanges in Dex B, call it , the price for USDC/ETH becomes 900 in Dex B. A searcher could

- Put a USDC to ETH transaction in DEX B: selling 900 USDC and get 1 ETH

- Put a ETH to USDC transaction in DEX A: selling 1 ETH and get 1000 USDC

and together would result in a 100 USDC net income. This example is demonstrated in Figure 3 below.

For an arbitrage to succeed, there’re two conditions, the first is that a price difference occurs in the DEX after someone exchanges, the second is that MEV searcher’s transactions are right after the ordinary user’s. The first condition is guaranteed because DEXs are self-executing programs that automatically enforce and execute the code, which means that everyone could calculate the price after the ordinary user’s transaction. The second condition is met if the MEV searcher is in charge of ordering transactions in a block.

Because searchers can see ordinary users’ transactions before they are included in blocks, when a searcher sees in the ‘mempool’, they will calculate the price in DEX B. If arbitrage is profitable, the searcher will generate and and create a block with transactions in the order to secure their profit.

Liquidation

Lending Protocols, like Aave, allow a user to collateralize assets of one type and borrow assets of another. If one wants to exchange from one asset to another without suffering from the price change in DEX, they may choose lending protocols. For example, Alice may use 1500 USDC as collateral, put that in a lending protocol, and borrow 1 ETH.

However, the prices of cryptocurrencies change all the time. When Alice (an ordinary user) initially stakes their USDC, 1 ETH may only be worth 1000 USDC. As the price of ETH increases, 1500 USDC may be worth less than 1 ETH. In this case, to avoid bad debt, the protocol will sell Alice’s collateral before the price of ETH reaches 1500 USDC. The selling point is the liquidation threshold, which is the percentage of the total value of debt borrowed. Selling/buying someone’s collateral to avoid bad debt is called liquidation. For Aave specifically, the protocol will sell Alice’s collateral when the price of ETH reaches 1237.5, corresponding to a liquidation threshold of 82.5%.

In this case, any buyer (MEV searcher) buying 1500 USDC with 1 ETH when the market price of ETH is only 1237.5 USDC has a net profit of 262.5 USDC. This 262.5 USDC is a risk-free profit because the buyer could buy 1500 USDC with 1 ETH and sell that 1 ETH in the same transaction using smart contracts.

Sandwich Trading

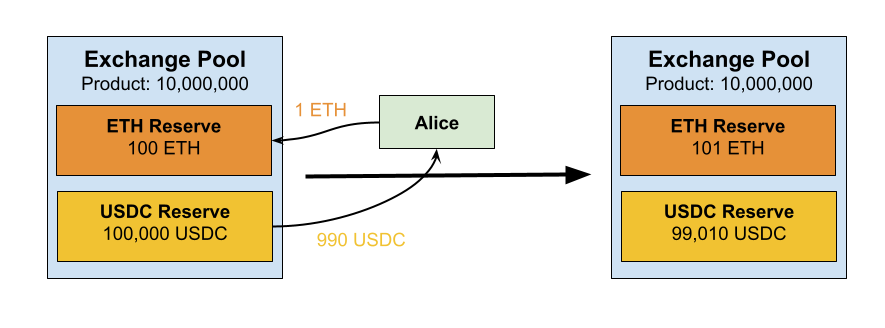

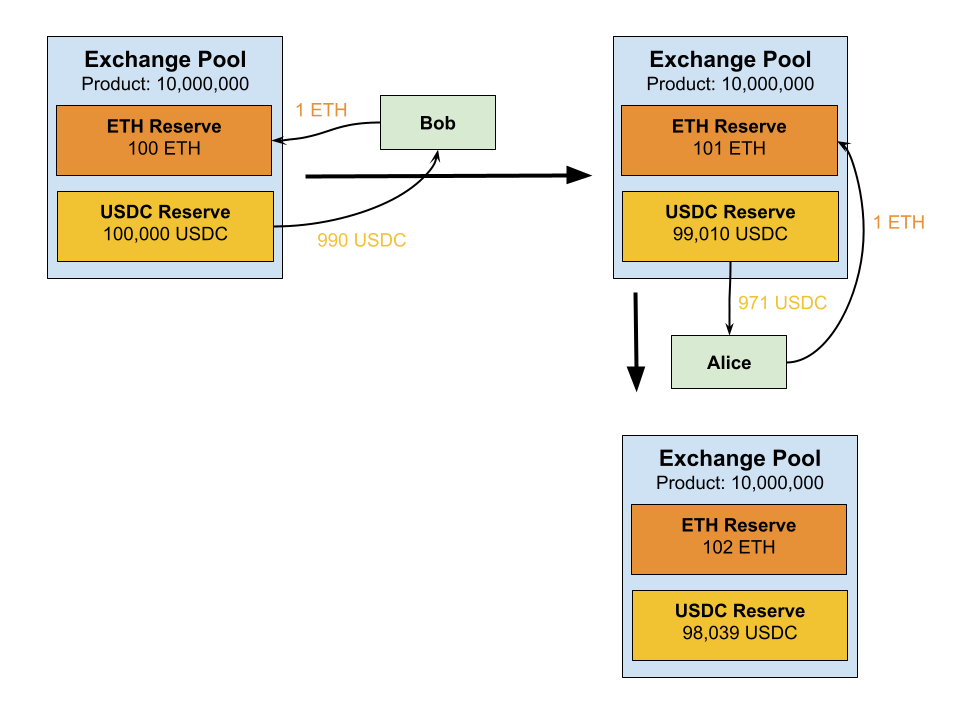

Another well-known MEV opportunity is sandwich trading. As we mentioned above, when we exchange from one asset to another in DEX, the price of the assets depends on the number of assets in the liquidity pool. For example, in Figure 4.a, Alice (an ordinary user) would like to trade 1 ETH to USDC. When Alice signs the transaction, the DEX has 100 ETH and 100,000 USDC; she would expect 990 USDC if the DEX is a constant product market maker, meaning that the product of two assets always stays the same.

However, as shown in Figure 4.b, if Bob sells 1 ETH before Alice, the liquidity pool would have 99,010 USDC and 101 ETH, and by the time Alice sells her 1 ETH, she could only receive 971 USDC. Alice cannot be sure when her transaction will be included in a block. There might be pending transactions in the mempool, or Bob may simply pay a higher priority fee.

Alice typically specifies the minimum price she is willing to accept, such as “I want to receive at least 950 USDC for my 1 ETH!” She avoids setting a high minimum price like “I want to receive at least 1000 (or higher) USDC for my 1 ETH!” to prevent potential delays or transaction failures due to infeasible prices. The former ensures a smoother transaction process, while the latter could lead to frustration.

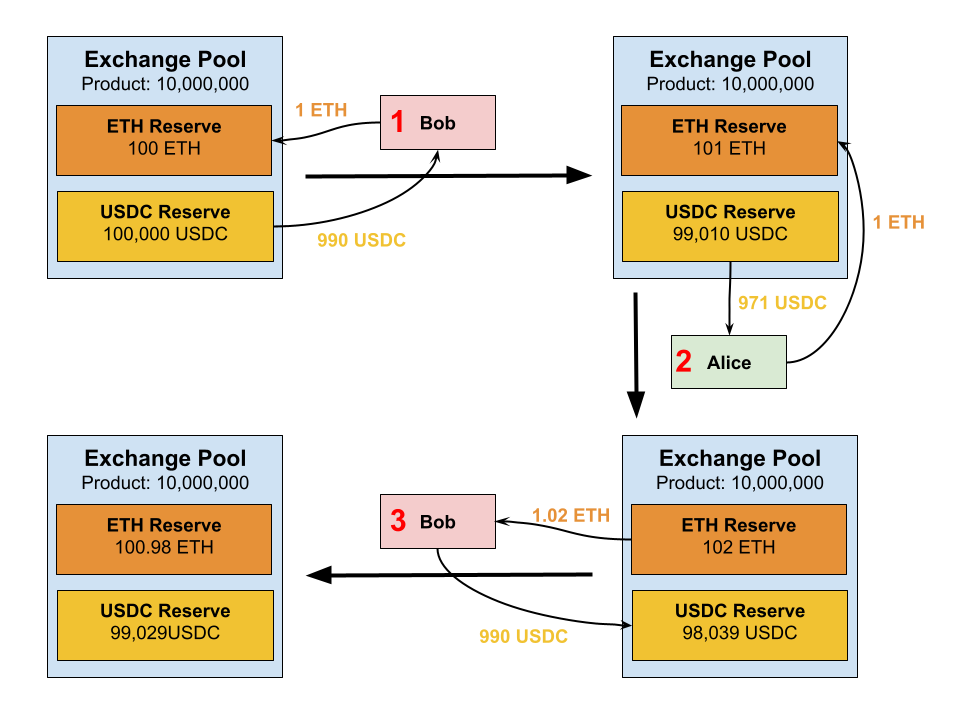

If Alice sets her minimum acceptable price at 971 USDC for her 1 ETH, Bob could exploit this as an MEV searcher. In Figure 4.c, by selling ETH before Alice, Bob could drive the price down to Alice’s minimum and then buy ETH after Alice’s transaction. The example below shows a net profit of 0.02 ETH from a 1 ETH transaction at a price of 1000 USDC/ETH. Once again, this is a risk-free profit, as all three transactions could occur in a single block, and if any one of them fails, all three transactions are reverted.

Ethereum Consensus Mechanism

In the previous section, we considered a simple model with only two players: ordinary users and MEV searchers. Now, we will introduce another player: proposers/miners.

Before 2022, Ethereum is using a proof of work consensus mechanism, the same as Bitcoin. Ethereum switched to a much more energy efficient consensus mechanism: Proof of Stake in 2022. The main idea related to MEV stays the same in both consensus mechanims.

In a blockchain system like Ethereum, the process begins when users (both ordinary users and MEV searchers) create and send transactions (actions they want to perform, like buying or selling tokens) to proposers/miners. When sending a transaction to proposers/miners, users specify the fees they’re willing to pay for block inclusion. Part of the fee goes to the Ethereum protocol and is destroyed; the rest goes to proposers.

These proposers collect a batch of transactions, organize them into a group called a block, and add this block to the blockchain. Once the block is added, the transactions within it are considered confirmed, meaning they are officially recorded and cannot be easily altered.

Proposers have significant control over which transactions to include in each block and the order in which they appear. This power allows them to potentially maximize their profits by prioritizing transactions in ways that are financially advantageous to them. For instance, they might choose to include transactions that offer higher transaction fees first.

To become a miner, one needs to start “mining” on your computer by running a program. To become a proposer, one needs to stake 32ETH to become a validator and every slot (12 seconds), a proposer is selected randomly among all validators by the Ethereum protocol.

Priority Gas Auction

In many cases, more than one MEV searcher may find the same MEV opportunities and compete for the block inclusion because only the first searcher could make profits from the same MEV opportunity; for example, if the liquidation has happened, the second searcher’s attempt will fail as the protocol has nothing to sell.

As we mentioned above, when miners/proposers bundle transactions into a block, they pick the transactions with the highest priority fee to maximize their profit.

MEV searchers, in this case, would run auctions publicly in the network for miners to include their transactions. For example, if searchers A and B found the same MEV opportunity with 1 ETH profit. A and B would each broadcast a series of transactions with the same content but an incremental gas fee. We call these transactions “bids” resembling bids in auctions. This auction process is termed priority gas auction (PGA). PGA was brought up initially before 2022 thus we’re using miners when explaining PGA.

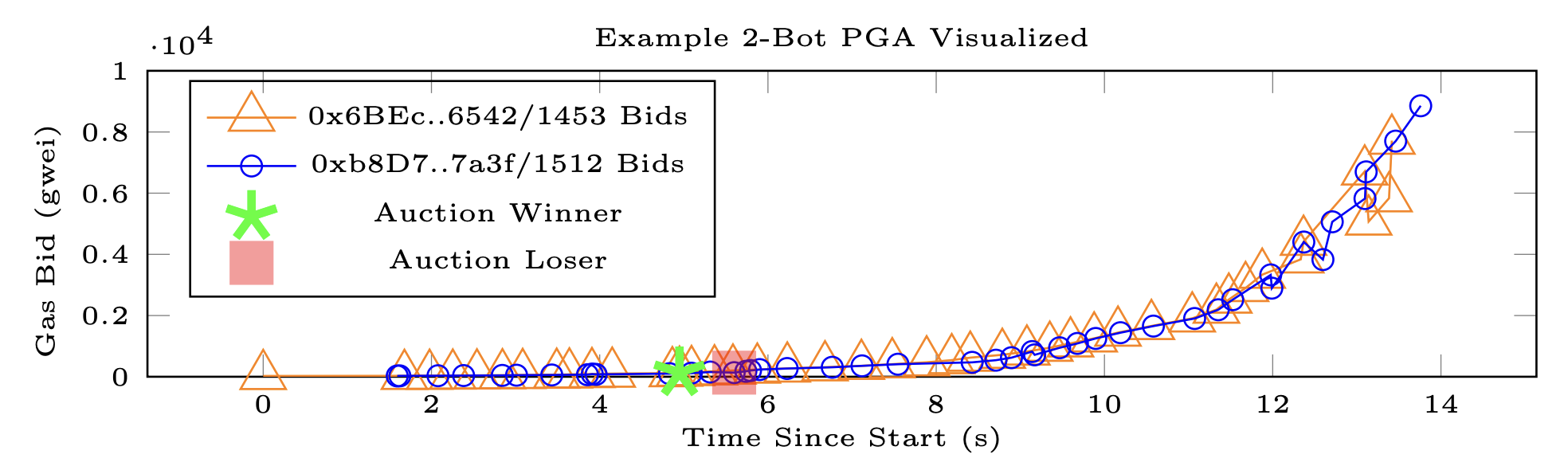

We use an example from Flash Boy 2.0 to illustrate this. Figure 4 below shows two searchers, 0x6B…6542 and 0xb8…7a3f, bidding for the arbitrage opportunity. We use triangles to represent a series of bids with different gas fees placed by 0x6B…6542 and circles for 0xb8…7a3f. The auction lasted 14 seconds, with both searchers gradually increasing the bid from gwei to roughly gwei. The green star and red rectangular are the two transactions included into the block.

PGA resembles a first-price-all-pay auction since when two players compete for the same MEV opportunities, and the second player’s transactions fail, they still need to pay a percentage of the gas fee for block inclusion.

In our example, the auction winner and loser are the two transactions with and gwei, respectively. Due to network delay, searchers were still updating gas fees after miners had included the transactions.

Problems caused by MEV and Current Solutions

Indeed, not all MEV transactions involve attacks. Even for sandwich trading, where a 2% loss occurs in each transaction, it can still be advantageous compared to traditional financial systems, where banks often charge between 0.5% to 5%. However, to extract past MEV, miners/proposers may re-org the chain history. This is an existential threat to Ethereum’s consensus security. Less severely, with searchers competing for block space in the open network, Ethereum suffers network congestion and chain congestion.

Problems: Network Congestion, Chain Congestion, and Time-bandit attack

The first problem brought by MEV is network congestion. When two searchers compete for the MEV opportunities to be included in the block, each will repeatedly reissue the transaction with a higher gas fee. This could be because of the bot’s bidding strategy or simply because the searcher noticed a higher bid in the peer-to-peer network. In our example above, 0x6B…6542 and 0xb8…7a3f issued 42 and 43 bids, respectively—this significantly increased network congestion.

In addition to that, chain congestion is also a problem. As we explained in our example, the miner would include both searcher A’s and B’s transactions because even if the transaction failed, the searcher still needs to pay a percentage of the gas fee simply for block inclusion.Failed transactions waste block space, artificially increasing block scarcity and resulting in a higher gas fee for ordinary users.

A more severe problem on Ethereum related to MEV is a time-bandit attack. Proposers could re-propose a subchain to extract the MEV profits. For example, the current block height is 100. Instead of proposing block 101, proposers could propose blocks 51 to 100 again so they could extract MEV profits in these 50 blocks.

Solution 1: Off-chain auctions between builders and searchers

To solve network congestion and chain congestion brought by MEV, Flashbots built an off-chain, first price, sealed bid auction system between builders and searchers called MEV-geth. Instead of doing PGA in the open network, searchers would privately send bundles to miners/proposers through MEV-geth.

Bundles are one or more transactions grouped and executed in a given sequence. Searchers are encouraged to set the gas price to 0 and pay builders for the block inclusion fee by using a special transfer function in the bundle. Miners/proposers would select the bundles with the highest bid and place this bundle at the top of the block—the winning bundle will be the first to be executed in a block, thus guaranteeing the success of the execution.

Searchers could guarantee the atomic execution of the bundle by using smart contracts, which is the same way they make profits risk-free. Thus, searchers will only pay the miners/proposers if their bundles are executed successfully.

What MEV-geth mitigates

MEV-geth resolves the network congestion because no communication between searchers and miners/proposers will happen in the peer-to-peer network. Meanwhile, MEV-geth resolves the chain congestion because miners/proposers will not include failed transactions as searchers set the gas price to 0. Including a failed transaction will give no reward to miners/proposers. MEV-geth is also preferred for searchers because they only pay miners/proposers if their MEV extraction is successful.

Drawbacks & Problem 4: unfair profits for solo validator

First, MEV-geth didn’t address the time-bandit attack. Miners/Proposers still have incentives to re-org the subchain to extract MEV. Second, after Ethereum switched to Proof of Stake in 2022, people started to notice that with searchers communicating with proposers off-chain, solo validators are making much less profit from MEV compared with the staking pool.

In Ethereum Proof of Stake, validators could be solo validators or join a staking pool with other validators. Consider a solo validator with 32ETH staked and a validity pool with 320ETH staked. While the pool has ten times more opportunities to extract MEV profits because they’re selected as proposers ten more times than solo validators, the pool is much more sophisticated in exploiting MEV opportunities compared to solo validators because they could spend much more effort on optimizing profits for each time they’re selected as proposer.

To help solo validators benefit from MEV, Vitalik proposed a system that outsources block building to a group of specialized players called builders, called Proposer Builder Separation.

Solution 2: Proposer Builder Separation (PBS)

In our previous model, we had three players: searchers, ordinary users, and proposers. In this section, we will introduce builders responsible for preparing full blocks that proposers will propose.

As we mentioned above, in Ethereum Proof of Stake, proposers are responsible for generating a full block by selecting transactions or bundles from those they received. In PBS, the full block is prepared by builders, and proposers only need to select the full block with the highest bid.

Anyone could be a builder. A builder is expected to build a block with the highest profit, including MEV profit and priority gas fees. Builders would bid for block proposing by broadcasting a block header, which contains the commitment to a block body and specifies the amount of reward they are willing to pay the proposers. The proposer then commits to proposing a specific block by signing the block header. After seeing the signature from the proposer, builders reveal the full block.

We need to update the underlying consensus mechanism to implement PBS on Ethereum. Currently, there are only two cases in a given slot: either the proposer broadcasts a block or not. However, with the PBS proposal as mentioned above, three cases could happen:

- Proposer didn’t commit on any block header

- Proposer commits on a block header, but the builder didn’t reveal the full block

- Proposer commits on a block header, and the full block is revealed

Therefore, a temporary solution is to implement an off-chain auction system between builders and proposers, where they could communicate off-chain on which block the proposer will propose. In this way, we keep the underlying Ethereum consensus mechanism unchanged.

MEV-boost: current off-chain implementation of PBS

Flashbot provided an OFF-CHAIN proposer builder separation API called MEV-boost that outsources block building to builders. Since the auction system between builders and proposers happens off-chain, a doubly trusted third party, relay, is needed here.

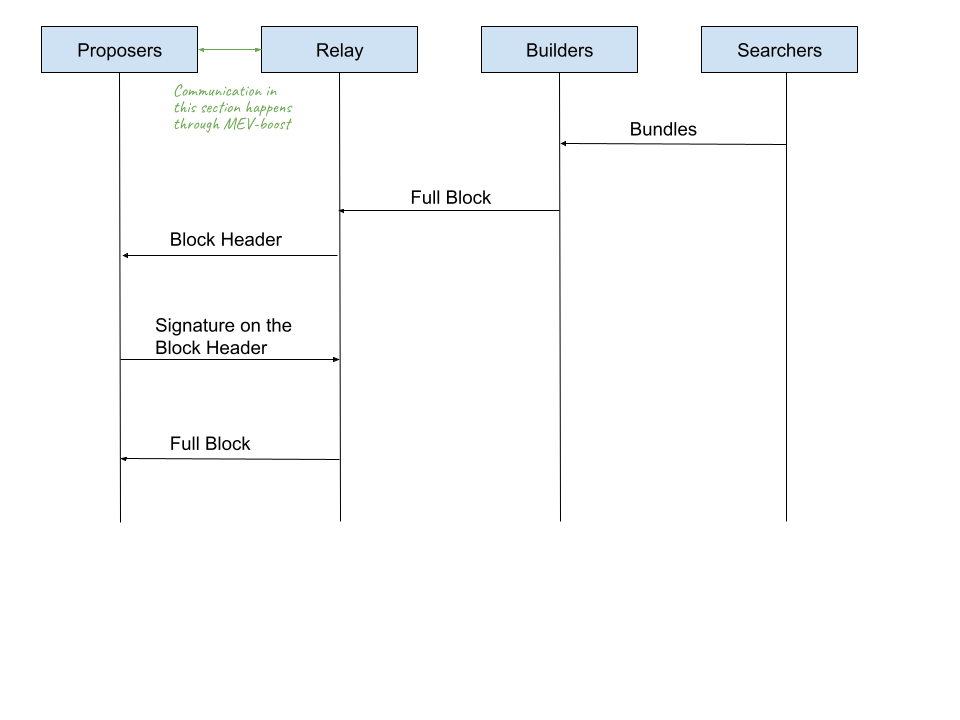

MEV-boost works as explained in Figure 5. In a given slot,

- Builders send the full block to a relay. In the last transaction in the block, the builder transfers some amount of ETH to the proposer; this is the bid to the proposer.

- Relay hides the details of the block, especially the last transaction, and sends just the block header and the bid amount to the proposer.

- The Proposer commits to proposing the block by signing the block header.

- Upon seeing the signature from the proposer, the relay reveals the full block to the proposer.

- Proposer proposes the block to other validators for voting.

In the current system, builders cannot send the full block directly to proposers without using a relay. This is because proposers could propose only the block’s last transaction. If the proposer needs to sign the header, there is no guarantee that the full block revealed by the builder includes the promised profit. The relay acts as a middleman that verifies the builders’ blocks and ensures that builders only get paid when the block is proposed. This is similar to how eBay acts as a trusted intermediary between buyers and sellers.

Problem 5: Timing Game

A big problem with MEV-boost is the existence of a doubly-trusted third party: relayers. Another issue in PBS (both with and without relays) is that proposers and builders may delay the block revealing time so they have more time for MEV extraction. A known consequence of this behavior is a missed slot.

In an honest case, a block should be proposed at the beginning of the slot, and selected validators would vote on the block within 4 seconds. However, a proposer could delay the release of the block so that just over 40% of selected validators voted on the block. With more time, they could collect more transactions and harvest the MEV profits on these additional transactions. This is called timing game. Timing game is possible and profitable, but not exploited yet. Time is Money