miniCodeProps: a Benchmark for Proving Code Properties

It is nearly inevitable that bugs will appear in a codebase during software development. To catch these bugs before they lead to real-world consequences, the formal verification community has developed a wide variety of tools for ensuring code correctness. These tools fall into two main classes: Automated Reasoning and Interactive Theorem Proving. Unfortunately, proving code properties with either of these approaches tends to require significant effort from human experts. In this blog post, we describe early steps towards using the emerging capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) to automate the labor intensive portions of the Interactive Theorem Proving paradigm. In particular, we introduce miniCodeProps , a benchmark for automated Interactive Theorem Proving on code properties.

Background

Verification with Automated Reasoning

Automated Reasoning tools such as boolean satisfiability solvers (a.k.a. SAT solvers) take formulas in a form of propositional logic as input and use “ brute reasoning ” to search for a variable assignment such that the input formula evaluates to True. If no such assignment exists, a proof of this fact is returned. If we want to verify that the outputs of a function \(y = f(x)\) satisfy property \(p(y)\), we can encode \(\exists x, \lnot p(f(x)) \) into CNF and run a SAT solver. If \(f\) fails to satisfy \(p\) on any input(s), the solver will return one such input as a satisfying assignment to the formula. Otherwise, the returned proof that the formula is unsatisfiable is equivalent to a proof that \(\forall x, p(f(x))\), i.e. \(f\) satisfies \(p\) on all possible inputs.

For example, \(f\) may be a function that takes an unsorted list of numbers \(x\) as input and returns \(y\), a new sorted list. If \(p(y)\) mathematically encodes the statement “the list \(y\) is ordered from least to greatest”, then solving the aforementioned \(\exists x, \lnot p(f(x)) \) is effectively asking the SAT solver to search for input lists that cause \(f\) to not return a sorted list. In practice, verifying a sorting algorithm requires proving other properties as well. If \(f\) always sets \(y\) to an empty list, \(p(y)\) will always be True! We follow up with this example in a later section .

Satisfiability Modulo Theory (SMT) solvers allow more complicated variable types such as integers and arrays, as well as clauses that use for-all quantifiers. These extensions make encoding correctness properties simpler, but make producing proofs of unsatisfiability much more difficult . While this formulation succeeds in many practical settings, solving SAT and SMT formulas is an NP-hard problem. In practice, when an input formula takes prohibitively long to solve, a human expert must modify the problem encoding by adding extra information such as an inductive invariant hint to reduce the search space. Although not the focus of this post, recent work has shown that OpenAI’s GPT-4 LLM can be used to reliably produce SMT encodings of some problems.

Verification with Interactive Theorem Proving

In contrast to the Automated Reasoning approach, Interactive Theorem Provers (ITPs) were explicitly designed to include a human expert in the proving process. Well known ITP environments such as Isabelle , Coq , and Lean require that the user specify the program and the property to be proved in mathematical languages unique to each ITP, which are about as expressive as the SMT language while maintaining more human readability. The user is then presented with the current state of the proof, containing the goal(s) and other relevant information. The user then adds lines to a growing proof of the property in which each line modifies the goal(s) in a mathematically valid way that is verified by the ITP until all goals are proven. At first glance, this paradigm seems far inferior to Automated Reasoning in terms of scaling potential because a human expert is an integral part of the proving process. However, recent advances in LLM capabilities provide hope that Artificial Intelligence (AI) will soon be able to automate proof writing in ITP environments.

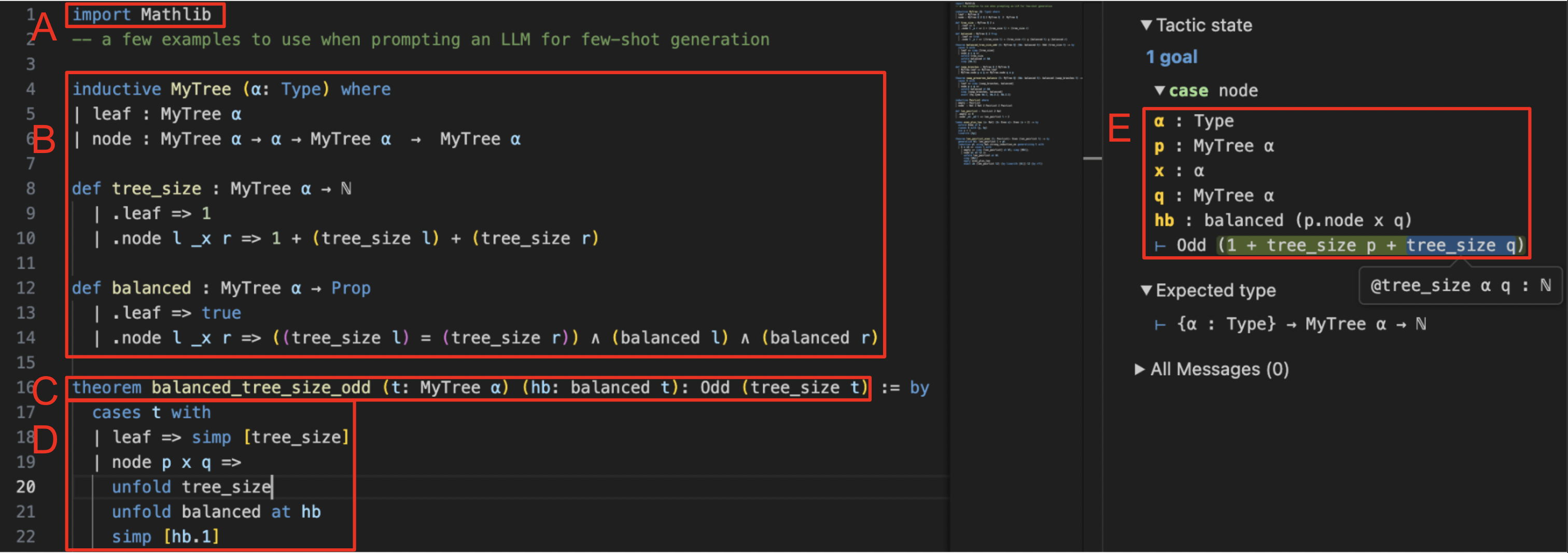

Our work uses Lean 4 to state and prove theorems about code. The image below is a sample Lean file containing two functions involving

binary trees

:

tree_size

and

balanced

(section B). Section C contains a property of these functions written

in Lean, namely that when

balanced

returns true on any tree

t

,

tree_size(t)

returns an odd number.

The definition of

Odd

is part of mathlib (Lean’s library of mathematical statements and theorems), which is imported in section A.

Section D contains the proof of this property. The proof state (section E) displays Lean’s internal proof environment at the location of the cursor, which in this case is

line 20 in section D. The yellow items in section E describe objects available for use in the proof, i.e.

p

and

q

are the left and right branches of the input tree.

The proof state also contains facts available for use in the proof, i.e.

hb

stores the fact that a tree with

x

as the root and

p

and

q

as branches is balanced.

The final line of section E is the “goal” of the proof, which by line 20 has been simplified to showing that adding 1 to the tree sizes of

p

and

q

results in an odd number.

New Applications of LLMs

Mathematical theorem proving

Mathematics research currently relies on extensive peer review to spot errors in new publications. This process can be difficult and time consuming, without any guarantees on review quality. To address this problem, several well-known mathematicians have begun to formalize parts of their work in Lean . From a computer scientist’s point of view, this context provides several possible avenues of research, such as generating new formal and informal proofs and translating between the two types. In this post, we focus on formal proof generation. Recently, LLMs fine-tuned on medium size formal math datasets such as Lean Mathlib have shown state of the art performance on the formal mathematical proof benchmark miniF2F (see lego-prover , llemma , Draft-Sketch-Prove , HTPS , DeepSeek-Prover , and this improved data sampling method ).

Code Generation

Code generation, modification, and repair have been active areas of research for decades. Recent work has shown significant progress on influential benchmarks such as HumanEval and MBPP . In principle, the advances in this area are directly applicable to formal theorem proving. Lean 4 is both a programming language and an ITP, so generating Lean proofs can also be viewed as generating code in the Lean programming language. Additionally, several code generation models can generate accompanying natural language explanations of generated code. If a language model can explain how code works, it may also be able to generate proofs of properties of said code.

Challenges and Mitigations

Although LLMs can prove formal mathematical theorems and explain generated code, the niche of proving program properties with LLMs is underexplored due to several technical challenges.

Incorporating Context

Until recently, input size constraints have been a well-known problem for LLMs. In particular, early LLMs could only process between hundreds and thousands of words at a time due to various architecture choices and constraints. Recent advances have significantly increased the effective allowed input size: see this post for an introduction to the topic. In early work on using LLMs for interactive theorem proving, only the proof state (see section E in the image above ) was used as input due to input size constraints. Increases in allowed input length have allowed prompts about code to also include code dependencies and file context, which are both useful to humans when reasoning about ITP proofs.

Hallucinations

As people use Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT more often and for an increasing variety of tasks, LLM hallucinations have garnered significant attention. Essentially, LLMs sometimes fabricate information that appears plausible but does not hold up under scrutiny. For example, an LLM might produce a proof that contains logical errors or uses nonexistent lemmas. Many partial solutions exist for handling hallucinations; some examples include self-consistency and Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) .

ITPs provide a somewhat unique context where hallucinations are caught immediately by the ITP’s internal verifier. When an LLM produces an invalid proof step, the error message produced by the ITP can also be used to prompt the LLM for an alternate proof step (see DeepSeek-Prover-V1.5 ), similarly to how humans interact with an ITP.

Benchmark Availability

In large part, progress on tasks such as code generation and (in)formal math proofs is driven by reporting progress on widely accepted benchmarks such as HumanEval , MATH , and miniF2F . At the time of writing, no such benchmark exists for proofs of code properties. The main contribution of our work in this field is the creation of miniCodeProps , a new benchmark containing a variety of programs and corresponding properties to be proven in Lean 4. We intend that miniCodeProps be used to benchmark the capabilities of LLMs to produce correct proofs of code properties.

Benchmark: miniCodeProps

miniCodeProps is intended to mirror the utility of miniF2F (a formal mathematical theorem proving benchmark) in the space of proving properties of code. We describe the way the benchmark was created and our baseline experiments with several techniques from code generation and theorem proving literature.

Benchmark Collection

The programs and associated properties in miniCodeProps were all sourced from the Tons of Inductive Problems (TIP) dataset. We selected files from TIP with properties describing functions defined in TIP, then translated those properties and functions from Haskell to Lean 4. During the translation process, we were required to prove several lemmas in Lean regarding the termination of the recursive functions being defined. These lemmas are also properties of the functions translated from TIP, and are also included in the benchmark. Each example in our benchmark contains the text of sections A, B, C, and E in the example above, where section E is the initial proof state. An automated ITP system succeeds on a given example by producing a correct section D, where correctness is verified by Lean. The next section explores the common methods such ITP systems use to produce proofs.

Methods

In this section we will address the following questions:

- How do you programmatically check generated proofs?

- What are current and potential future techniques used to generate proofs using LLMs?

There are two main classes of proof generation techniques in current automated ITP literature:

- Next-Step tactic prediction: one line is generated at a time until the proof is complete

- Full-Proof generation: entire candidate proofs are generated until a proof is found In practice, researchers designate a computational budget (for example, 8 attempts at Full-Proof generation) and terminate the proof search process once this budget is reached without a successful proof. We evaluate both approaches on miniCodeProps.

Interaction with Lean

Interaction with the Lean 4 kernel is necessary for most Next-Step tactic generation and self-refinement Full-Proof generation methods. Our work uses the Lean REPL , a tool that facilitates backtracking and continuing from specific steps in the proof. Each time Lean code is generated, Lean REPL checks the validity of the line in the context of the definitions and earlier proof lines. The REPL returns error messages if any invalid steps were taken, or the new proof state containing the list of remaining goals (statements to prove) otherwise. When the list of goals in the proof state is empty, the original theorem has been proven correct.

Next-Step Tactic Generation

At the beginning of a proof and after each valid line, the Lean kernel generates a proof state, i.e. a collection of the variables and hypotheses defined in the current context

(section E of

the earlier example

).

As Lean is also a programming language, the proof state can also be thought of as a debug trace of the current context (theorems are effectively functions that produce certificates that a property holds! See

Curry-Howard

). Tactics are functions that modify the proof state. Common examples include

simp

, a

broadly useful simplification tactic that attempts a wide array of other common tactics, and

rw

, which attempts to use specific lemmas provided by the user to modify the goal.

The most basic variant of Next-step tactic generation is a function from proof state to a set of possible next tactics. There are many ways to extend this idea. For example,

expanding the input to include other relevant Lean code and lemmas or expanding output to give each possible next tactic a “confidence” score describing the likelihood that the proof

can be completed using the generation as the next tactic. In the earlier example, a successful Next-Step tactic prediction given the proof state in section E would be the line

after the cursor in section D, i.e.

unfold balanced at hb

. To produce a full proof, the system starts from the initial proof state and repeatedly generates possible next tactics

until the proof state has an empty list of goals.

Full-Proof Generation

Researchers have discovered that LLMs in some cases exhibit In-Context Learning : the ability to generalize patterns from a small number of examples provided in the prompt. Additionally, the data that massive LLMs such as GPT-4 are trained on contains examples of proofs in Lean 3, as well as in other proof assistants such as Isabelle and Coq. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that LLMs could generate full proofs of a given theorem statement given example pairs of theorem statement and proof. Concretely, the “theorem statement” used is generally sections A, B, C, and optionally E in the earlier example , while the expected output is an entire valid proof (section D). In our experiments we ignored initial proof state (section E) as it was mostly redundant with the theorem definition (section C) in our examples.

Deciding inputs and outputs is a good first step, but it is generally suboptimal to just send the LLM a list of input-output pairs. The nascent field of Prompt Engineering provides a variety of approaches to constructing high-performing prompts for language models. One such technique is to tell the language model it is an expert, i,e, begin with “You are an expert in producing Lean 4 proofs tasked with…”. A second common approach is “few-shot prompting,” the approach of providing several examples of input and desired output in the prompt. Another common approach is self-refinement , i.e. using any available output describing the results of the previous LLM output as an input to the next prompt.

miniCodeProps Baselines

We tested several models using Next-Step tactic generation, and GPT-4 for Full-Proof generation. Results can be found in the table below. LLMStep is a framework for getting Next-Step proof suggestions from arbitrary LLMs in VScode. We modified it to communicate with Lean REPL directly and output confidence scores for each generated next step. We applied the following proof search approach:

- Given proof state, generate 10 (next tactic, confidence score) pairs.

- Deduplicate and pick the 5 highest confidence tactics.

-

Send each tactic to Lean REPL using the current state. For each valid proof state returned:

- If the proof state is invalid (i.e. the tactic caused Lean REPL to error), ignore it.

- If there are no goals remaining, return the list of steps taken.

- If the max proof search depth has not been reached, repeat steps 1-3 on the new proof state. The LLMs we used were all fine-tuned to produce Lean tactics from proof state. ntp-context-1.3b in particular was also fine-tuned to use surrounding file context. Due to computational constraints, we used a proof search depth of 3 in our experiments.

For our Full-Proof generation approach, we constructed a base prompt containing three examples of program property proofs similar to those in miniCodeProps. For each property in miniCodeProps, we appended the property and accompanying context (function definitions and lemmas) to the base prompt and requested a full proof. We requested 8 responses from GPT-4 and reported success if any succeeded.

| Method | LLM | Medley (Easy) | Termination (Med) | Sorting (Hard) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Step | Pythia2.8b | 44/86 | 1/28 | 0/63 |

| Next-Step | Llemma7b | 46/86 | 2/28 | 0/63 |

| Next-Step | ntp-context-1.3b | 38/86 | 0/28 | 0/63 |

| Full-Proof | GPT-4-turbo | 44/86 | 1/28 | 0/63 |

Our results indicate that proving properties of programs is nontrivial for simple applications of fine-tuned language models and basic few-shot prompting of GPT-4. Further analysis of the failure modes of these models (see Sorting Discussion ), as well as more sophisticated (and higher computational budget) approaches to proof search will likely improve these results in the near future. In the following section, we analyze the Sorting component of miniCodeProps and a sample incorrect proof generated by GPT-4.

Discussion: Sorting

The Sorting section of miniCodeProps contains a variety of sorting algorithms with associated properties. In particular, after defining 11 sorting algorithms on lists of natural numbers, TIP defines the following properties for each algorithm:

- the algorithm returns an ordered list

- the list returned by the algorithm has the same number of elements as the input list

- the list returned by the algorithm is a permutation of the original list

- the algorithm is equivalent to another sorting algorithm (insertion sort)

Properties 1 and 4 are deeply connected; there is a unique way to order a list of natural numbers. However, this fact itself is a property of the

ordered

function used!

The best way to prove property 4 for most algorithms may very well be proving property 1 and that single fact about lists of natural numbers, but I argue that any

theorem prover that does so has demonstrated a valuable skill. The property 2 is also strictly easier than property 3. This allows for interesting analysis of future

theorem provers: will they succeed on proving property 2 but struggle on property 3? Or, will they prove property 3 directly and use its corollary to immediately prove property 2?

Unfortunately, the approaches we have tested so far have not succeeded at proving any properties of sorting algorithms. However, the ways in which they fail are informative. Below we

have a sample output of GPT-4 attempting to prove that heapsort (

hsort

below) returns an ordered list. The proof

looks

mostly reasonable to a Lean user, a common characteristic

of LLM-produced output. Notable problems occur on lines 25, 31, and 40.

1 inductive MyHeap where

2 | nil : MyHeap

3 | node : MyHeap → Nat → MyHeap → MyHeap

4

5 def numElem : MyHeap → Nat

6 | MyHeap.nil => 0

7 | MyHeap.node p _x q => 1 + numElem p + numElem q

8

9 lemma numElem_merge_branches_lt (p q: MyHeap) (x: Nat): numElem (hmerge p q) < numElem (MyHeap.node p x q) := by

10 rw [←merge_elems _ _];

11 have h': numElem (MyHeap.node p x q) = 1 + numElem p + numElem q; rfl

12 rw [h']

13 linarith;

14

15 def ordered : List Nat -> Bool

16 | [] => True

17 | [_x] => True

18 | x::y::xs => x <= y && ordered (y::xs)

19

20 -- hsort (heapsort) omitted for brevity

21

22 theorem prop_HSortSorts' (xs: List Nat) : ordered (hsort xs) == True := by

23 unfold hsort

24 unfold ordered

25 induction xs generalizing MyHeap with

26 | nil => unfold toHeap; unfold toList; simp

27 | cons x xs' ih =>

28 unfold toHeap

29 unfold toList

30 unfold hmerge

31 have h := numElem_merge_branches_lt ... -- Placeholder for specific heaps if needed

32 have m := merge_elems ... -- Placeholder for specific heaps if needed

33 specialize ih (xs'.map (fun x => MyHeap.node MyHeap.nil x MyHeap.nil))

34 induction (toList (toHeap xs')) generalizing (toList (toHeap (x :: xs')))

35 | nil =>

36 apply ih

37 | cons y ys' ysih =>

38 unfold toList at ih

39 unfold toHeap at ih

40 unfold ordered at ih ⊢

41 unfold hsort at ih

42 have h := numElem_merge_branches_lt ... -- Placeholder for specific values if needed

43 have m := merge_elems ... -- Placeholder for specific values if needed

44 case h_1 =>

45 unfold ordered

46 simp [List.map]

47 simp [toList]

48 case h_2 =>

49 unfold toHeap

50 unfold ordered

51 simp [toList]

52 rfl

On line 25, GPT-4 attempts to generalize

MyHeap

, a type of object defined earlier. Induction with generalization

is a common idea in many proofs of recursive programs, but the object generalized is always some object in the proof context, not a type. Generalizing a type of object is semantically

meaningless, and indeed the lean kernel throws its first error on this line.

On line 31, GPT-4 again demonstrates interesting but incorrect behavior.

numElem_merge_branches_lt

is a lemma stating that merging two heaps results in a heap with fewer elements

than a heap with a new value at the root and the two original heaps as children. GPT-4 invokes this lemma, but does not provide any arguments instead using

...

(not valid Lean syntax),

seemingly trying to tell the user “I don’t know what should go here, so you fill it in.” However, the

h

that GPT-4 names this invocation is not used in the proof. I interpret this as follows: GPT-4’s model of correct Lean proofs includes invoking lemmas defined in the context, but does not include the logic necessary to effectively use such lemmas.

Conclusion

Our baselines for miniCodeProps demonstrate that despite recent advances in LLM-powered mathematical theorem proving in ITPs, proving complex code properties remains difficult. While future work on benchmarking this capability will likely expand outside of TIP to include properties of the wide range of non-inductive functions and data, miniCodeProps represents a challenging first step. When models are capable of automatically producing proofs in the Sorting category, theorem proving technology will have taken a large step towards the elusive goal of automatic generation of provably correct code. We hope the theorem proving community finds miniCodeProps useful for improving the capabilities of automated ITP systems.

Reference List

- miniCodeProps on Arxiv

- miniCodeProps benchmark

- What is an LLM blog post

- CNF explanation

- Brute Reasoning explanation

- SAT solver unsatisfiability proofs

- SMT solver proofs

- Clover: Closed-Loop Verifiable Code Generation

- GPT-4 Technical Report

- Lean homepage

- Binary Tree explanation

- Terrence Tao formalizing parts of his work in Lean

- Enhancing Neural Theorem Proving through Data Augmentation and Dynamic Sampling Method

- Large Language Models Meet NL2Code: A Survey

- MBPP Dataset

- Natural Language Generation and Understanding of Big Code for AI-Assisted Programming: A Review

- Context Length blog post

- LLM Hallucinations blog post

- SelfCheckGPT: Zero-Resource Black-Box Hallucination Detection for Generative Large Language Models

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks

- DeepSeek-Prover-V1.5: Harnessing Proof Assistant Feedback for Reinforcement Learning and Monte-Carlo Tree Search

- miniF2F dataset

- Tons of Inductive Problems (TIP) dataset

- Lean REPL

- Curry-Howard Correspondence

- a Survey on In-Context Learning

- Self-Refine: Iterative Refinement with Self-Feedback

- LLMStep

- Pythia2.8b fine-tuning

- Llemma7b fine-tuning

- ntp-context-1.3b fine-tuning

- OpenAI documentation for GPT-4-turbo