Oblivious Maps for Trusted Execution Environments

\[ \gdef\lf{\left \lfloor} \gdef\rf{\right \rfloor} \]

Imagine using a popular messaging app that includes a contact discovery feature to find which of your phone contacts are already using the service and to get information on how to communicate with them. While convenient, this process raises significant privacy concerns: how can you discover mutual contacts without revealing your entire contact list to the messaging app's server?

In a standard implementation, the app might upload your entire contact list to the server to perform the matching, potentially exposing sensitive information to unauthorized access. To address this issue, we need a solution that allows for secure contact discovery without compromising user privacy.

One approach is to leverage Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs), like Intel SGX, to perform these operations securely on the server. TEEs create isolated environments where code and data can be processed without being accessible to the rest of the system. This means that even if the server's operating system is compromised, the information inside the TEE remains protected.

By implementing an oblivious map inside a TEE, we can ensure that neither the app's server nor potential attackers learn anything about your contact list or which queries you performed. Being oblivious means that no information is revealed from the CPU's memory access patterns, making it an ideal solution for privacy-preserving applications.

This blog post explores our research on ENIGMAP [6] , an efficient external-memory oblivious map designed for secure enclaves, offering significant performance improvements over previous work. ENIGMAP enables privacy-preserving contact discovery and other applications by protecting sensitive data and queries from unauthorized access even from the operating system of the machine where ENIGMAP is running.

Background

Before we can dive into the details of ENIGMAP, we first need to understand a few basic concepts, including sorted maps, background on TEEs, external-memory and oblivious algorithms.

Sorted Map

In ENIGMAP, our goal is to implement an oblivious sorted map. A sorted map of size \(N\) is a data structure that can store up to \(N\) key-value pairs and efficiently supports the following operations:

- Get(key) -> value: Returns the value associated with the key, or None if the key was not set before.

- Set(key, value): Sets or updates the value of the key.

- Delete(key): Removes the key from the map.

- RangeQuery(keyMin, keyMax) -> [(key, value)]: Returns all the key-value pairs in the specified range.

A search tree, such as a B+ tree or an AVL tree, is typically used to implement a sorted map. Following previous work [5] , we chose to use an AVL tree. 1

AVL tree

An AVL tree of size \(N\) is a binary search tree with at most \(N\) nodes, and the following properties:

-

binary tree - a tree where each node has a key, a value, and at most 2 children.

-

search tree - the key of every node is larger than the key of every node on its left subtree and smaller than the key of every node on its right subtree.

-

AVL invariant - the height of the two child subtrees of any node differs by at most one.

The maximum height of an AVL tree of size \(N\) is \( 1.44 \log_2 N\), and

Search(key)

,

Insert(key,value)

and

Delete(key)

operations – with their standard semantic meaning – can be implemented

2

to only access \( O(\log N) \) nodes by doing a binary search for

key

on the tree.

3

Figure 2

-

An example AVL tree. Each node is represented only by its key. To search for the key 26, we would touch the nodes on the path from the root: 42, 20, 27 and 26.

Figure 2

-

An example AVL tree. Each node is represented only by its key. To search for the key 26, we would touch the nodes on the path from the root: 42, 20, 27 and 26.

To implement a map using an AVL tree,

Get

,

Set

and

Delete

get translated to the equivalent operations on a binary search tree (

Search

,

Insert

and

Delete

), while

RangeQuery

can be implemented by Searching for

KeyMin

and iterating over the next values on the map until we hit

KeyMax

.

Ok. So we know AVL trees can be used to implement a map efficiently. Great! But, how can we hide the content of our queries from an attacker who runs the machine where the map is now?

Well, this is where Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) come into play. Rather than trusting standard cryptographic assumptions like Computational Diffie-Hellman or the existence of one-way functions, we instead trust… Intel.

TEEs and External Memory

Trusted Execution Environments

(TEEs), like Intel SGX, provide isolated execution environments for sensitive computations. They ensure that data and code running inside of a secure memory region called an

enclave

are protected from external tampering and observation, even if the operating system is compromised. However, TEEs come with limited secure memory, which poses a challenge for applications to handle large datasets securely.

The “Enclave Assumption” – code inside an enclave runs under the crash-fault model (it either runs the correct computation or crashes, without unexpected behaviors); all of its memory contents are encrypted and cannot be accessed by any other applications running on the same machine; and the speed of code execution is similar to if it was not inside of an enclave.

To manage datasets that don't fit in the TEE, data must frequently be swapped between the secure enclave memory - called the Enclave Page Cache (EPC) - and insecure external memory (RAM or disk). This swapping process, known as page swapping, can significantly impact performance due to the overhead of moving data in and out of the enclave, context switching, and the need to encrypt and decrypt data during these transfers. In fact, we manually measured the cost of external memory accesses (Figure 2) - in SGXv2 copying a page from external memory to the EPC is about 47x-80x slower than copying the same amount of data inside of the EPC.

Optimizing the number of external memory page swaps is crucial for enhancing the performance of applications running in TEEs.

Figure 2

-

Cost of PageSwap operation of 4KB relative to a MOV of 4KB inside of enclave protected memory. A page swap is about 47

times more expensive than moving 4KB in memory within the enclave.

The costs are color-coded which shows the cost breakdown, blue is the cost of EWB/OCall.

EWB

- enclave write back (the mechanism used by the operating system to swap enclave pages),

OCall

-

using SGX

's

OCall mechanism so the enclave application manually swaps pages

.

Figure 2

-

Cost of PageSwap operation of 4KB relative to a MOV of 4KB inside of enclave protected memory. A page swap is about 47

times more expensive than moving 4KB in memory within the enclave.

The costs are color-coded which shows the cost breakdown, blue is the cost of EWB/OCall.

EWB

- enclave write back (the mechanism used by the operating system to swap enclave pages),

OCall

-

using SGX

's

OCall mechanism so the enclave application manually swaps pages

.

Additionally, all the accesses to the external memory can be seen by the operating system and thus by an attacker running the server. Therefore, these accesses should not reveal any information about the client's queries. This is where oblivious algorithms come into play.

Oblivious Algorithms

An oblivious algorithm is an algorithm that doesn't leak any information about its inputs to an attacker that has access to a trace of the algorithm's execution.

In the context of TEEs there are 3 traces to consider:

-

The addresses of external memory accesses - when we need to access disk, the operating system can always see which disk pages we accessed without any physical attacks [3] .

-

The addresses of every RAM access inside of the TEE protected memory - in SGX, it is still the operating system that manages memory pages; therefore the operating system can know at the page level which addresses were accessed [3,4] .

-

The instruction trace - the list of executed instructions, since the way CPU fetches instructions is by reading RAM addresses [4] .

Algorithms that are oblivious with respect to only 1) are typically called

weakly oblivious

or

external memory oblivious

; while algorithms that are oblivious with respect to 1), 2) and 3) are called

strongly oblivious

or simply

oblivious algorithms

.

In this blogpost we will focus on

strongly oblivious algorithms

. In this notion:

-

All the traces above are public. Only the traces of the CPU registers and CPU caches are private.

-

The limited enclave-protected memory is encrypted and accessible to the enclave, even though its memory access trace is public 4 .

-

The external memory is public, and therefore the enclave needs to encrypt data before moving it there.

Oblivious Algorithms in practice

So, how do oblivious algorithms look like in practice? Lets consider the following function:

const int PASSWORD_SIZE;

char CORRECT[PASSWORD_SIZE];

bool check_password_nonoblivious(char input[PASSWORD_SIZE]) {

for (int i=0; i<PASSWORD_SIZE; i++) {

if (CORRECT[i] != input[i]) return false;

}

return true;

}

Listing 1 - A non-oblivious version of the check_password function - based on the number of instructions executed an attacker can learn the size of the common prefix between CORRECT and input

In

Listing 1

, the attacker can infer how many initial characters of the input are correct based on the number of memory accesses that

check_password

used - therefore it is not an oblivious algorithm. To make it oblivious we can make the number of memory accesses independent of the input:

bool check_password_oblivious(char input[PASSWORD_SIZE]) {

bool ret = true;

for (int i=0; i<PASSWORD_SIZE; i++) {

bool condition = CORRECT[i] != input[i];

ret = ret * condition; // if (!condition) ret = false;

}

return ret;

}

Listing 2 - An oblivious version of the check_password function - the memory access trace is now constant. 5

If you are familiar with constant-time cryptography you probably noticed that this oblivious algorithm is in fact also a constant-time algorithm . These two notions are closely related - if an attacker knows the number of memory addresses accessed, then the attacker has the information needed for timing attacks.

However, compared to constant-time algorithms - where we only need to care about the computation time being constant - the oblivious notion is stronger - we also need to make sure every single address we access does not leak any information. Even accessing a single array index can leak information about the data being processed:

int access_array_nonoblivious(int Array[MAX_SIZE], int i) {

return Array[i];

}

Listing 3 - A non-oblivious array access

When we call

access_array_nonoblivious

, we will access the memory address

(A+i)

. If an the attacker can see every address we use, then the attacker can learn if two calls to this function have the same arguments. To protect against this, we could again rely on a constant time algorithm - by scanning the entire array every time we need to access a single index,making use of the Conditional Mov x86 instruction -

CMOV(cond, target, value)

.

The

CMOV(cond, target, value)instruction assignsvaluetotargetifconditionis true, but always fetchestargetandvaluefrom memory, resulting in a constant memory trace.

int access_array_linear_scan(int Array[MAX_SIZE], int index) {

int ret = 0;

for (int j=0; j<MAX_SIZE; j++) {

CMOV(j==i, ret, Array[i]);

}

return Array[i];

}

Listing 4 - An oblivious array access via linear scan - this takes time 6 \( O( \) MAX_SIZE \() \)

While using a linear scan for each array access ensures obliviousness, it is highly inefficient - we need to transverse the whole array every time we want to access a single element. However, this kind of linear scan solution is used in practice, for instance, Signal used it along with other techniques to offer Private Contact Discovery .

To address this inefficiency, more sophisticated methods to hide which index of an array is accessed have been developed that no longer have a constant memory access trace, but instead a random-looking one, like PathORAM.

PathORAM

Path Oblivious RAM (PathORAM) [1] is an efficient protocol designed to hide the access patterns to an array of size \(N\). The key insight for PathORAM is that rather than doing a linear scan to create a constant trace, we keep dynamically moving data in unprotected memory, so that the memory access trace is indistinguishable from that of accessing random positions in the array - so nothing can be inferred about which indexes we are accessing from the memory access trace.

Interface for PathORAM

PathORAM provides a straightforward interface:

void Access(bool readOrWrite, int addr, int& pos, int& data)

Performs a read or write operation (

readOrWrite) on the specified addressaddrreading or writing todata. The positionposhas information about where the specified address is stored and is updated foraddrafter each call to access. It is up to the callee to keep track ofposfor each address 7 .

In PathORAM each address is assigned a random position in {0..N} that identifies where that address is stored in public memory (we will see how soon). This position is leaked after each access call; therefore after each access call, a new random position is generated for that address. (We will explain how to keep track of all the positions for a binary search tree in the next section - Oblivious Data Structures - for now, just assume there is a way to keep track of the position for each address)

How PathORAM works

In PathORAM, each array index is stored as a block:

template <typename T>

struct Block{

int address;

int position; // only used if the block is in the stash

T data;

}

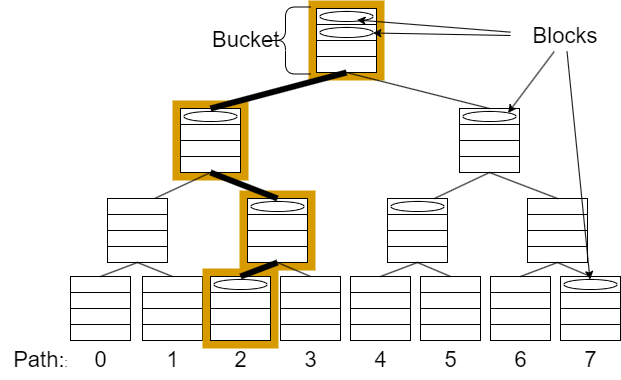

PathORAM has two major structures:

-

Stash - where we keep recently accessed blocks. The stash has a constant maximum size and is accessed using linear scans.

-

ORAM Tree (Figure 3) - an almost 8 complete binary tree with \(N\) leaves where each node is called a Bucket and can have up to

Z(typicallyZ=4) blocks of data. Whenever we access this tree, we will leak which nodes are being accessed in the trace.

The

position

mentioned in the PathORAM interface identifies a unique path from the root to a leaf in this tree. If an address has a given position, then its block can be stored in any bucket on the path corresponding to that position.

Figure 3

-

A visualization of PathORAM tree with

Figure 3

-

A visualization of PathORAM tree with

Z=4

where path 2 - the path with all the buckets that could contain position 2 is highlighted.

When we construct the ORAM, every address is assigned a random

position

, and is placed in some bucket in the corresponding path

7

. When the access operation is called, the PathORAM algorithm does the following steps:

-

Read Path - Move, from the ORAM tree to the stash, all the blocks on the path identified by the original position of the address.

-

Generate new position - Generate a new random position for the address we just accessed.

-

Stash Operation - Do a linear scan over the stash to do the read/write operation on the address we want, and update its position.

-

Stash Eviction - Pick a random path, and try to obliviously move blocks from the stash to this path - without revealing how many blocks were moved and the locations they were moved to. After this operation, the remaining number of blocks in the stash is below a small constant with very high probability 9 .

Provided we can keep track of the positions in some way (see section Oblivious Data Structures ), we can do the access operation in an ORAM of size \(N\) in \( O(\log N \log\log^2 N) \) (non-private) memory accesses. 7

Let's see now how can we keep track of the node positions for a binary search tree.

Oblivious Data Structures

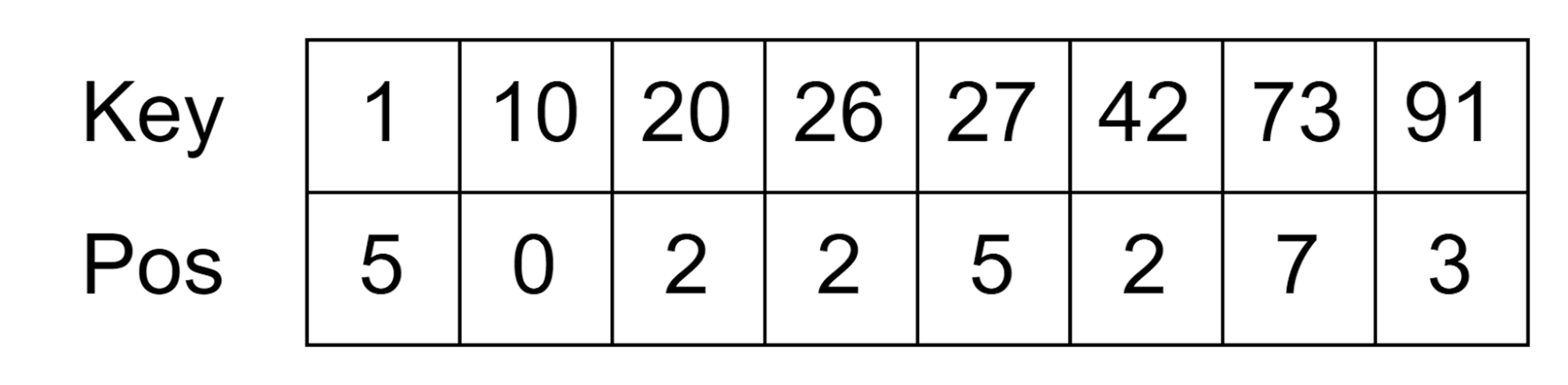

In order to keep track of the positions of all the nodes in a binary search tree, we can use an insight from the Oblivious Data Structures (ODS) paper [2] :

We only need to store the position of the root node - since every operation in a binary search tree always accesses the nodes starting from the root of the binary search tree, we can store in each node the position of its two children directly (See Figure 4).

This works, since when we want to access the children of a node, we can generate ahead of time the new random position for its children and store it in the parent before actually accessing the children.

Figure 4

-

A visualization of the logical AVL tree and how it is mapped to the PathORAM tree. We only need to keep track that node 42 is in position 2. Its children (node 20 and 73) have their position information (2 and 7 respectively) stored inside node 42.

Figure 4

-

A visualization of the logical AVL tree and how it is mapped to the PathORAM tree. We only need to keep track that node 42 is in position 2. Its children (node 20 and 73) have their position information (2 and 7 respectively) stored inside node 42.

This insight from ODS was previously implemented by P. Mishra et al. in Oblix [5] , where an oblivious AVL tree was used to develop an oblivious map. In ENIGMAP, we build on the insight from ODS to develop an oblivious AVL tree, with practical optimizations related to TEEs.

ENIGMAP

Our main contributions with ENIGMAP are:

-

Identifying external memory accesses as an important cost of oblivious algorithms in TEEs (Figure 2).

-

An asymptotically and concretely faster strongly oblivious sorted map both in number of instructions executed as well as external memory accesses (section Main Query Optimizations ).

-

A faster initialization algorithm for oblivious maps, making it practical for large database sizes (section Fast Initialization Algorithm ).

So, let's take a look at a few of the optimizations done in ENIGMAP!

Main Query Optimizations

Optimization 1 - Locality Friendly Layout for the ORAM tree

To improve the locality of data accesses, ENIGMAP leverages concepts from cache-oblivious algorithms and van Emde Boas (vEB) layout [8] . By organizing the ORAM tree in a cache-efficient manner, we reduce the number of page swaps needed to access a path, significantly improving access times 10 .

When we want to access an AVL tree node, we need to call

Access

on the ORAM to get that AVL tree node (recall from Figure 4 that each AVL node is stored in the ORAM), and therefore we will have to read all the Buckets in the path where that AVL tree node is stored. In the external-memory these buckets will be stored in pages, which are read atomically, but typically can include \(B\) buckets.

If we were to store the buckets in heap layout - this is level by level left to right - we would have to read \( log{N} \) pages, since apart from the first few levels, all the buckets would end up in different pages (see Heap Layout in Figure 5).

Instead, ENIGMAP uses a locality friendly layout 11 - we find out the size of the largest ORAM subtree that fits in a page (its height is \( \lf log_2{B} \rf \) ) and store subtrees of that size together in the disk page (see Our Layout in Figure 5) . This optimization allows to only have to read \( log{\frac{N}{B}} \) pages per ORAM access.

Figure 5

-

Comparison of Heap Layout with the Layout used in ENIGMAP considering B=3. Each triangle/rectangle represents a disk page. Red - pages read while accessing the same certain path. To read a given path ENIGMAP reads an optimal number of pages (3 in the example), while the Heap layout will read one page per bucket (5 in the example).

Figure 5

-

Comparison of Heap Layout with the Layout used in ENIGMAP considering B=3. Each triangle/rectangle represents a disk page. Red - pages read while accessing the same certain path. To read a given path ENIGMAP reads an optimal number of pages (3 in the example), while the Heap layout will read one page per bucket (5 in the example).

Optimization 2 - Ensuring integrity and freshness with low cost

Another key optimization that comes from the locality friendly layout is that we can ensure integrity and freshness of data in external memory with almost no extra cost. Since we always access ORAM pages in a path from the root and each friendly-layout subtree corresponds to a disk page, we can build a Merkle tree of the friendly-layout subtrees. Each subtree is encrypted with AES-GCM, and stores the nonce of its children subtrees encryptions. The main application only needs to keep the nonce of the root subtree to ensure integrity and freshness.

Figure 6

-

Achieving integrity protection efficiently in external memory on a tree can be done with a Merkle-tree. The fact we have subtrees packed together allows us to have good nonce-size to data-size ratio.

Figure 6

-

Achieving integrity protection efficiently in external memory on a tree can be done with a Merkle-tree. The fact we have subtrees packed together allows us to have good nonce-size to data-size ratio.

Optimization 3 - Multi-level caching + batching

ENIGMAP employs a multi-level caching scheme to optimize data access:

-

Page-Level Cache : Outside the enclave, this cache reduces the frequency of page swaps from disk. 12

-

Bucket-Level Cache : Inside the enclave, it caches frequently accessed data to minimize external-memory calls, specifically we cache the top levels of the ORAM tree to always be inside the enclave.

-

AVL-Tree node Cache : This cache is specifically designed to optimize searches within the AVL tree. It is implemented by temporarily marking AVL nodes as sticky - these nodes should stay in the stash during eviction, until we mark them as non-sticky. If a node is sticky, we can just access it directly via a linear scan from the stash, without paying the ORAM overhead. We use this optimization in two ways:

- AVL tree top caching - the first few AVL levels during search can just be accessed via linear scan.

- AVL batched operations - when we do an AVL tree insertion, we need to do two passes over the same AVL path. In the first pass, we mark all the nodes we will have to access as sticky, so that on the second pass we can access them faster via a linear scan of the stash.

We encourage you to read about about further optimizations and how each of these optimizations impacts performance in our paper [6] .

Fast Initialization Algorithm

Imagine we have a array of \(N\) key-value pairs, and want to initialize an oblivious map with them. The simplest solution (Naive Solution), would be to start with an empty map, and call

Set(key, value)

once for each key-value pair - this would cost us \(N\) AVL Tree insertions. We can do better!

Instead of doing \(N\) insertions, we construct the AVL tree with all the values all at once.

This works in two phases:

-

Phase 1 - we build the logical AVL tree nodes with the correct random positions assigned.

-

Phase 2 - we place the nodes into the ORAM tree obliviously, using a PathORAM initialization algorithm.

In order to better understand our algorithm, we will go over it step by step with an example. For the sake of simplicity, we will represent each key-value pair in the initial array by its key:

Phase 1 - AVL Tree Construction

In the first phase, our goal is to build the AVL tree, by assigning random positions to all the nodes, and correctly assigning children and storing the children's position on each node such that the AVL tree properties are preserved.

We start by obliviously sorting

13

the array and assigning random positions to each node

14

:

Notice that any sorted array represents an implicit binary search tree with the AVL property - doing a binary search on the array corresponds to traversing a binary search tree. So now, we need to correctly store the children positions on each node:

To do so, we use the

Propagate

procedure -

Listing 5

. For our example, the propagate algorithm for our array should be called as

Propagate(arr, 0, 7)

.

struct AddrPos {

int addr;

int pos;

};

struct Node {

int key;

AddrPos left, right;

AddrPos ap; // exists only during the construction algorithm.

};

AddrPos Propagate(vectorExternalMemory<Node>& nodes, int left, int right) {

int curr = (left + right) / 2;

int size = right - left + 1;

if (size == 1) return nodes[curr].ap;

nodes.MarkSticky(curr);

nodes.left = Propagate(nodes, left, mid-1);

nodes.right = Propagate(nodes, mid+1, right);

nodes.MarkNotSticky(curr);

}

Listing 5 - Propagate procedure pseudocode

Propagate

will be called once for each node. Every time we access a node, we mark it as sticky it so it won't be swapped into external memory and then recurse on each child to get its position and keep updating the indices. This means each node will be transferred at most once from external memory, and at any given time we will only have at most \(\log N\) nodes marked as sticky - since that is the maximum tree depth. Therefore, this algorithm will incur at most \(N\) external memory transfers.

Notice that the memory access pattern is oblivious since it depends only on the length of the array, and not on the content of the key-value pairs themselves.

Apart from the initial sorting, each Phase 1 stage does a linear number of external memory accesses and computation steps.

Phase 2 - PathORAM Initialization

The second phase of the algorithm is an ORAM initialization algorithm - we have the content of all the block, as well as randomly assigned positions for each block, and now we want to place them in the ORAM tree without leaking where each block is stored. We encourage you to read about it in our paper [6] .

For now, let's take a look at the performance of ENIGMAP.

Results

In order to evaluate ENIGMAP, we compare the performance of each map operation against two implementations:

-

Signal's Linear Scan Solution - It does a linear scan of the whole database for a batch of \( \beta \) queries, indexing each entry of the database on an hashtable built obliviously from the batch of queries.

-

Oblix [5] - The previous state of the art. It also uses an ODS-based AVL tree.

Experimental Setup

- Database Size (N): We tested with varying sizes, up to 256 million entries.

- Batch Size (\( \beta \)): Because Signal's solution is optimized to work with batches of queries, we introduce the parameter \( \beta \) to define the number of queries in a batch. We used batch sizes of 1, 10, 100, and 1000 queries.

- SGX Setting: In this blogpost we report results for a large EPC size (192GB) 15 , on a machine with 256GB of non-EPC RAM. Please refer to our paper for other settings, such as a small EPC size (128mb).

- Key size: All the keys in the experiments have 8 bytes each.

Get

Latency

We analyzed the performance of doing batches of \( \beta \)

Get

operations on each map implementation, in terms of latency and throughput.

At a database size of \(2^{26}\), ENIGMAP achieves a throughput speedup of 2x on

Getqueries, while maintaining a latency perGetof 0.45ms compared to Signal's 930ms and Oblix's 11ms.

At a database size of \(2^{32}\), ENIGMAP achieves a throughput speedup of 130x on

Getqueries, while maintaining a latency perGetof 2ms compared to Signal's 133000ms. 16

Asymptotics

| Scheme | Page Swaps | Compute |

|---|---|---|

| Signal | \( O\left(\frac{N}{B}\right) \) | \( O(N + \beta^2) \) |

| Oblix | \( O\left(\beta \log^2 N\right) \) | \( O\left(\beta \log^3 N\right) \) |

| ENIGMAP | \( O\left(\beta \log_B N \log N\right) \) | \( O\left(\beta \log^2 N \log \log N\right) \) |

Table 1 - Cost of a batch of \( \beta \)

Get

queries, on a map with N elements, page size B (key-value pairs) and EPC of size M (key-value pairs)

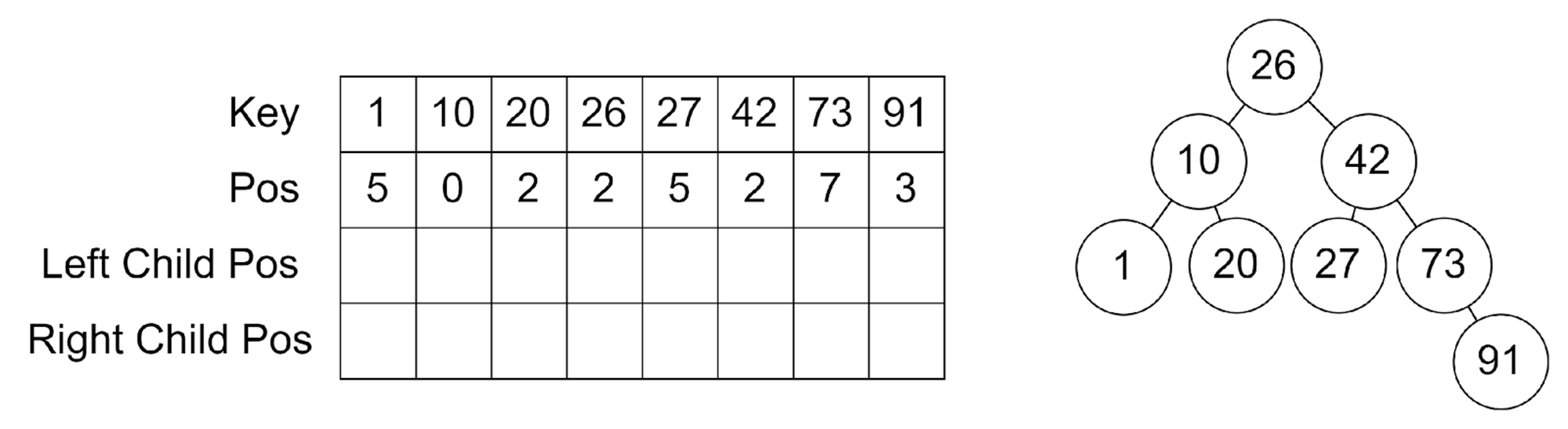

Experimental Latency

Figure 7

-

Comparison of ENIGMAP and Signal on

SGXv2. Enclave memory size is 192GB, RAM size is

256GB. The vertical lines mark when ENIGMAP and Signal

start to incur RAM and disk swaps, respectively. Comparison with Oblix in our paper is done through relative comparison to Signal (refer to Figure 9 in

[5]

)

Figure 7

-

Comparison of ENIGMAP and Signal on

SGXv2. Enclave memory size is 192GB, RAM size is

256GB. The vertical lines mark when ENIGMAP and Signal

start to incur RAM and disk swaps, respectively. Comparison with Oblix in our paper is done through relative comparison to Signal (refer to Figure 9 in

[5]

)

Figure 7 shows that:

- In terms of latency (measured at \(\beta=1\)), ENIGMAP always outperforms Signal (and Oblix).

- In terms of throughput, for batch sizes of 10, 100 and 1000, ENIGMAP starts to outperform Signal at a database sizes of \(2^{17}\), \(2^{22}\), and \(2^{25}\), respectively. Signal's quadratic computation term on the batch size makes it perform worse with batches larger than the ones tested.

In our paper, we also analyze the query performance of Insertions and Deletions, as well as analyzing the same experiments with different EPC and external memory constraints.

The key takeaway is that for medium and large database sizes (larger than \(2^{25}\) entries), ENIGMAP's throughput always outperforms the linear scan solution, making clear the superiority of ODS for TEEs.

Initialization

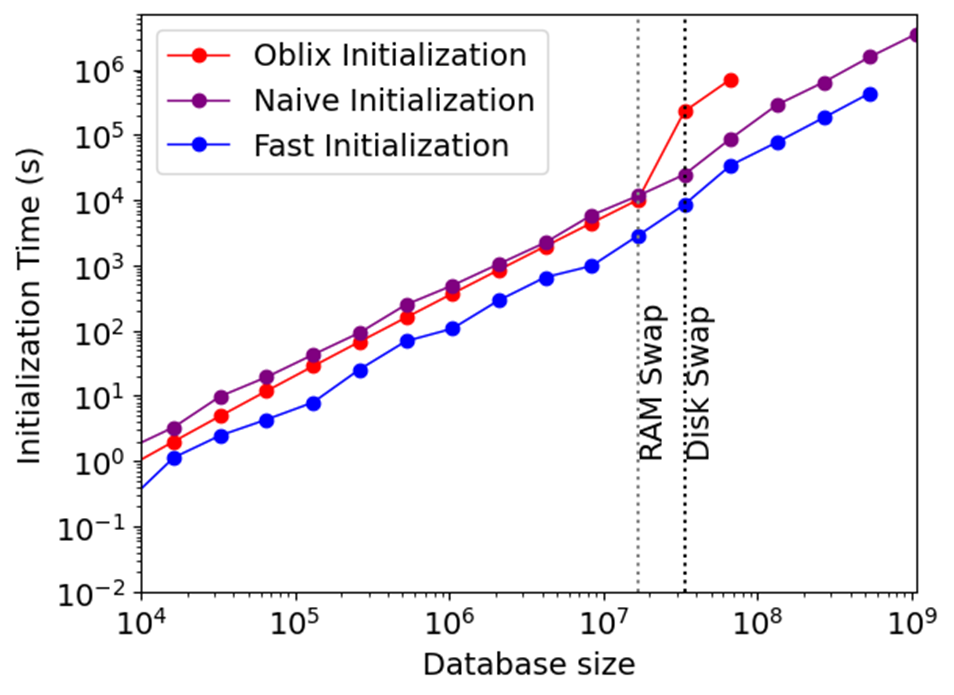

We analyzed how long it takes to initialize an oblivious map of \(N\) entries.

At a database size of \(2^{26}\), ENIGMAP's initialization takes 9.5h, a speedup of 18x compared to Oblix, but much slower than the few minutes Signal's needs to create an enclave and write the key-value pairs to enclave memory.

Initialization - Assymptotics

| Scheme | Page Swaps | Compute |

|---|---|---|

| Signal | \( O\left(\frac{N}{B}\right) \) | \( O(N) \) |

| Oblix | \( O\left(\frac{N}{B} \log^2 N\right) \) | \( O(N \log N) \) |

| ENIGMAP | \( O\left(\frac{N}{B} \log_{\frac{M}{B}} \frac{N}{B}\right) \) | \( O(N \log N) \) |

Table 2 - Cost of initializing a map with N elements, page size B (key-value pairs) and EPC of size M (key-value pairs)

Initialization - Experimental

Figure 8

-

Initialization cost of ENIGMAP (Fast), compared to our implementation of Oblix's initialization and to the Naive Initialization - doing \(N\) insertions on the database

Figure 8

-

Initialization cost of ENIGMAP (Fast), compared to our implementation of Oblix's initialization and to the Naive Initialization - doing \(N\) insertions on the database

Figure 8 shows that ENIGMAP's initialization outperforms Oblix's by 2-18x depending on the database size. This improvement in initialization time is crucial for making ODS practical for larger database sizes. However, at 9.5h for \(N=2^{26}\), ENIGMAP's initialization is still much slower than Signal's linear scan initialization, which only takes a few minutes since it only needs to create a large enclave and copy the key-value pairs there. 17

Results Summary

ENIGMAP shows significant improvements in query performance, achieving faster throughput and lower latency compared to Signal's linear scan solution and Oblix's ODS-based AVL tree. Specifically:

-

Query Throughput : ENIGMAP consistently outperforms both Signal and Oblix. At larger database sizes, ENIGMAP achieves up to 130x speedup over Signal for

Getqueries. This makes it highly efficient for handling large volumes of queries in practical applications. -

Query Latency : ENIGMAP maintains low latency per query, making it suitable for real-time applications. For example, at a database size of \(2^{26}\), ENIGMAP's latency per

Getis 0.45ms compared to Signal's 930ms and Oblix's 11ms. This significant reduction in latency ensures quick response times for individual queries.

While ENIGMAP excels in query performance, its initialization time is slower compared to Signal's solution. This tradeoff highlights that while ENIGMAP's initialization is slower, its higher throughput and low latency make it highly practical for applications where query performance is more critical than initialization time.

Applications, Limitations and Open Problems

ENIGMAP's Oblivious Sorted Map has a broad range of applications:

- Secure Databases : A sorted map can be used to build databases that protect the privacy of user queries. This is especially relevant for sensitive data such as medical records, financial transactions, and personal communication logs.

- Private Contact Discovery : Similar to the use case implemented by Signal, ENIGMAP can help in securely finding mutual contacts without revealing the contact list to the server.

- Cloud Computing : With the increasing reliance on cloud services, ensuring data privacy and security is paramount. ENIGMAP allows users to securely store and query data on untrusted cloud servers while maintaining the confidentiality of their access patterns. In this setting the external memory is no longer RAM or Disk, but the remote cloud server itself.

- Multi-party computations (MPC) : MPC and Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) provide encrypted computations similar to Intel SGX, but rely on strong cryptographic primitives rather than trusting hardware vendors like Intel. In MPC, it is crucial for algorithms to be oblivious to prevent information leakage through data access patterns. Traditionally, maps in MPC have been implemented using linear scans or an online phase of Private Information Retrieval (PIR) or Oblivious RAM (ORAM). ENIGMAP can serve as an efficient implementation of online ORAM in MPC, offering significant performance enhancements.

While ENIGMAP presents significant advancements, it also comes with certain limitations to address in future work:

Initialization Time : The initialization time for ENIGMAP is slower compared to simpler solutions like Signal's linear scan. For large databases, this initialization time can be a bottleneck. Future work should explore how to minimize the initialization time of ORAMs/ODSs in the TEE setting; there is still room for improvement. In [7] we developed a TEE external-memory optimized oblivious sorting algorithm that significantly improves ORAM initialization time; however, even with this optimization, ENIGMAP's initialization is still significantly slower than Signal. Exploring using other types of BSTs instead of AVL, or improving the ORAM initialization can also help improve initialization time.

Memory Overheads : The use of oblivious algorithms and PathORAM requires additional memory to store metadata, such as positions and encrypted blocks, as well a linear amount of fake metadata used to store fake blocks, which may be a constraint in memory-limited environments.

Exploring other BST implementations : In non-oblivious databases, typically B+ trees, AVL trees, skip-lists, or variations of them are used for indices. It would be interesting to explore in depth the tradeoffs between each of these solutions.

Our code is available on github , as well as ongoing work on more efficient oblivious maps .

Footnotes:

In our research, we considered both AVL trees and B+ trees. We opted for AVL trees in ENIGMAP because previous work had successfully used them, and for the specific problems we were addressing, the key and value sizes were relatively small. If range queries were not required, a hash table could be a faster alternative to a search tree.

To learn how each of the operations are implemented, the wikipedia page on AVL trees is a great starting point.

Having a bounded height and number of nodes that are touched during an operation is needed so that the time it takes to do a query doesn't leak information about the query. Since the tree depth is at most \( 1.44 \log_2 N\), we can make every

Search

operation always touch \( 1.44 \log_2 N\) nodes, potentially accessing fake nodes after we found the

key

we were looking for.

We need to use

*

instead of

&&

because in C++ the

&&

operator short circuits.

The granularity of the public memory access trace for Intel SGX is typically at the page level (4KB pages).

Both number of CPU instructions as well as number of memory accesses whose trace is public.

An almost complete binary tree of size N is a binary tree with N leaves where all the levels except the last one are full. The last level should have the N leftmost leaves only.

The failure probability is negligible in the stash size - the probability of the stash becoming larger than K after an operation is \( o(2^{-K}) \) [1] .

I suggest reading the PathORAM paper [1] for more details on why the stack size is kept constant, how initialization works, and the recursive ORAM technique used to keep track of the positions of all the addresses.

This locality-friendly layout is useful also in the scenario where we don't have a disk, since it can also translate to RAM pages that don't need to be cached, or it can also make trees with smaller nodes fit in CPU cache lines directly.

This is not the Embe Boas layout - we don't need to be cache-agnostic, since we know the page size for disk and SGX - and can even experimentally measure it, as you can find in our paper.

This cache is not as useful in SGXv2/TDX, since all the RAM can be used as part of the enclave.

Oblivious Sorting can efficiently be done on an array of size N in time \(O(N \log^2 N)\) [7] .

If the key-value pairs are already sorted by key, we can instead just verify it using a linear scan.

These larger EPC sizes have weaker security guarantees - EPC memory in RAM no longer has a freshness check, therefore the hardware TCB is no longer just the CPU, but all of the machine hardware instead. There has been a shift in industry interest towards larger enclaves sizes recently as they become available on cloud datacenters. The assumption of trusting the hardware is addressed by a “proof of cloud” - a cloud provider signs they are running the enclave and, since there is pottentially a huge economical loss if the cloud providers lies, developers can trust the hardware is not being tampered with. Since this is now a utility-based model, in large EPCs, trusting an SGX enclave will follow the Crash-Fault model is now risk management rather than an expected guarantee.

The Oblix paper does not report results for database sizes over \(2^{30}\), but even using the time for \(2^{28}\), we achieve a speedup of at least 53x, which further increases with database size.

Not all hope is lost in terms of initialization time; from our ongoing experiments, we believe the initialization time for binary search trees can be further improved, if we move away from AVL trees.

Bibliography

-

E. Stefanov, M. Van Dijk, E. Shi, T.-H. H. Chan, C. Fletcher, L. Ren, X. Yu, and S. Devadas. “PathORAM: An Extremely Simple Oblivious RAM Protocol” Journal of the ACM (JACM) 65, 4, Article 18 (August 2018), 26 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3177872

-

X. S. Wang, K. Nayak, C. Liu, T.-H. H. Chan, E. Shi, E. Stefanov, and Y. Huang. “Oblivious Data Structures” Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS ’14) , Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2014, pp. 215-226. https://doi.org/10.1145/2660267.2660314

-

V. Costan and S. Devadas. “Intel SGX Explained” Cryptology ePrint Archive , Report 2016/086. https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/086.pdf

-

J. V. Bulck, F. Piessens, and R. Strackx. “SGX-Step: A Practical Attack Framework for Precise Enclave Execution Control” Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on System Software for Trusted Execution (SysTEX’17) , Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 4, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1145/3152701.3152706

-

P. Mishra, R. Poddar, J. Chen, A. Chiesa, and R. A. Popa. “Oblix: An Efficient Oblivious Search Index” 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP) , San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018, pp. 279-296. https://doi.org/10.1109/SP.2018.00045

-

A. Tinoco, S. Gao, and E. Shi. “EnigMap: External-Memory Oblivious Map for Secure Enclaves” 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23) , Anaheim, CA, August 2023, pp. 4033-4050. https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity23/presentation/tinoco

-

T. Gu, Y. Wang, B. Chen, A. Tinoco, E. Shi, K. Yi. “Efficient Oblivious Sorting and Shuffling for Hardware Enclaves” Cryptology ePrint Archive , Report 2023/1258. https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/1258

-

M. A. Bender, E. D. Demaine, and M. Farach-Colton. “Cache-oblivious b-trees” SIAM J. Comput. , 35(2):341–358, 2005. https://erikdemaine.org/papers/CacheObliviousBTrees_SICOMP/paper.pdf