Better streaming algorithms for Maximum Directed Cut via 'snapshots'

\[ \gdef\bias{\mathrm{bias}} \gdef\deg{\mathrm{deg}} \gdef\indeg{\mathrm{indeg}} \gdef\outdeg{\mathrm{outdeg}} \gdef\Snap{\mathrm{Snap}} \gdef\RSnap{\mathrm{RefSnap}} \]

In this blog post, I’ll discuss a new algorithm based on two joint papers of mine with Raghuvansh Saxena, Madhu Sudan, and Santhoshini Velusamy (appearing in SODA’23 and FOCS’23). The goal of this algorithm is to “approximate” the value of a graph optimization problem called “maximum directed cut”, or Max-DICUT for short, and the algorithm operates in the so-called “streaming model”. After defining these terms, I will describe how we reduce the problem of approximating the Max-DICUT value of a directed graph to the problem of estimating a certain matrix, which we call the “snapshot”, associated to a directed graph; finally, I will present some ideas behind streaming algorithms for estimating these snapshot matrices.

Introduction

To start, we will define the particular algorithmic model (streaming algorithms) and computational problem ( Max-DICUT ) that we are interested in.

Streaming algorithms

Motivated by applications to “big data”, in the last two decades, theoretical models of computing on massive inputs have been widely studied. In these models, the algorithm is given limited , partial access to some input object, and is required to produce an output fulfilling some guarantee related to that object. Some classes of models include:

- Property testing , where an algorithm must decide whether a large object either has some property \(P\) or “really doesn’t have \(P\)” 1 given only a few queries to the object. Depending on the specific model, the algorithm may be able to choose these queries adaptively, or, more restrictively, the queries might just be randomly and independently sampled according to some distribution.

- Online algorithms , where an algorithm is forced to make progressive decisions about an object while it is revealed piece by piece.

- Streaming algorithms , where an algorithm is allowed to make a decision about an object after seeing it revealed progressively in a “stream”, but there is a limit on the amount of information that can be stored in memory.

This blog post is concerned with streaming algorithms. In this setting, memory space is the most important limited resource. Sometimes, there are even algorithms that pass over a data stream of length \(n\) but maintain their internal state using only \(O(\log n)\) or even fewer bits of memory! One exciting aspect of the streaming model of computation is that space restrictions can often be studied mathematically from the standpoint of information theory, opening an avenue for proving impossibility results. 2

Numerous algorithmic problems have been studied in the context of streaming algorithms. These include statistical problems, such as finding frequent elements in a list (so-called “heavy hitters”) or estimating properties of the distribution of element frequencies in lists (like so-called “frequency moments”), as well as questions about graphs, such as testing for connectivity, or computing the maximum matching size, where the stream consists of the list of edges. The common denominator between all these problems is that the “usual” algorithms might not be good streaming algorithms, whether because they require too much space or because they require “on-demand” access to the input data.

Constraint satisfaction problems

Many “classical” computational problems can be recast into questions in the streaming model. Here, we are interested in one class of problems that have been particularly well-studied classically, namely constraint satisfaction problems (CSPs). These occur often in practice and include many problems one might encounter in introductory algorithms courses, such as Max-3SAT , Max-CUT , and Max-\(q\)Coloring .

CSPs are defined by variables and local constraints over a finite alphabet. More formally, a CSP is defined by:

- A finite set \(\Sigma\), called an alphabet ; in the typical “Boolean” case, \(\Sigma=\{0,1\}\).

- A number of variables , \(n\).

-

A number of local

constraints

, \(m\), and a list of constraints \(C_1,\ldots,C_m\). Each constraint \(C_j\) is defined by four objects:

- A number \(k_j \geq 1 \in \mathbb{N}\), called the arity , that determines the number of variables \(C_j\) involves.

- A choice of \(k_j\) distinct variables \(i_{j,1},\ldots,i_{j,k_j} \in \{1,\ldots,n\}\).

- A predicate (or “goal” function) \(f_j : \Sigma^{k_j} \to \{0,1\}\) for those variables.

- A weight \(w_j \geq 0\).

The CSP asks us to optimize over potential assignments , which are functions \(x : \{1,\ldots,n\} \to \Sigma\) mapping each variable to an element of \(C_j\). In particular, the objective is to maximize 3 the number of “satisfied” (or “happy”, if you’d like) constraints, where a constraint \(C_j\) is “satisfied” if the alphabet symbols assigned by \(x\) on the variables \(i_{j,1},\ldots,i_{j,k_j}\) satisfy the predicate \(f_j\). The maximum number of constraints satisfied by any assignment is called the value of the CSP.

Some examples of CSPs are:

- In Max-CUT (a.k.a. “Maximum Cut”), the alphabet is Boolean (\(\Sigma = \{0,1\}\)), and all constraints are binary and use the same predicate: \(f(x,y) = x \oplus y\) (where \(\oplus\) denotes the Boolean XOR operation). I.e., if we apply a constraint to the variables \((i_1,i_2)\), then the constraint is satisfied iff \(x(i_1) \neq x(i_2)\). Max-\(q\)Coloring is similar, over a larger alphabet of size \(q\), with the predicate \(f(x,y)=1 \iff x \neq y\).

- In Max-DICUT (a.k.a. “Maximum Directed Cut”), the alphabet is again Boolean, and the predicate is now \(f(x,y) = x \wedge \neg y\), so that a constraint \((i_1,i_2)\) is satisfied iff \(x(i_1) = 1 \wedge x(i_2) = 0\).

- In Max-3SAT , the alphabet is also Boolean, all constraints are ternary, and the assorted predicates are all possible disjunctions on literals, such as \(f(x,y,z) = x \vee \neg y \vee z\) or \(f(x,y,z) = \neg x \vee \neg y \vee \neg z\).

Both Max-CUT and Max-DICUT can be described interchangeably in the language of graphs , which might be more familiar. For Max-CUT , given an instance on \(n\) variables, we can form a corresponding undirected graph on \(n\) vertices, and add an edge \(i_1 \leftrightarrow i_2\) for each constraint \((i_1,i_2)\) in the instance (with the same weight). Now an assigns each vertex to either \(0\) or \(1\), and an edge is satisfied iff its endpoints are on different sides of the cut. (We can think of an assignment as a “cut” which partitions the vertex-set into two sets: one side corresponding to the variables \(\{i : x(i)=0\}\) and one for \(\{i : x(i)=1\}\).) For Max-DICUT , because of the asymmetry, we have to create a directed graph. We add an edge \(i_1 \to i_2\) for each constraint \((i_1,i_2)\), and an edge \(i_1 \to i_2\) is satisfied iff \(i_1\) is assigned to \(1\) and \(i_2\) to \(0\). (Similarly, an assignment is an “ordered” partition of the vertex into two sets, i.e., we have a designated “source” set and “target” set and they are not interchangeable.)

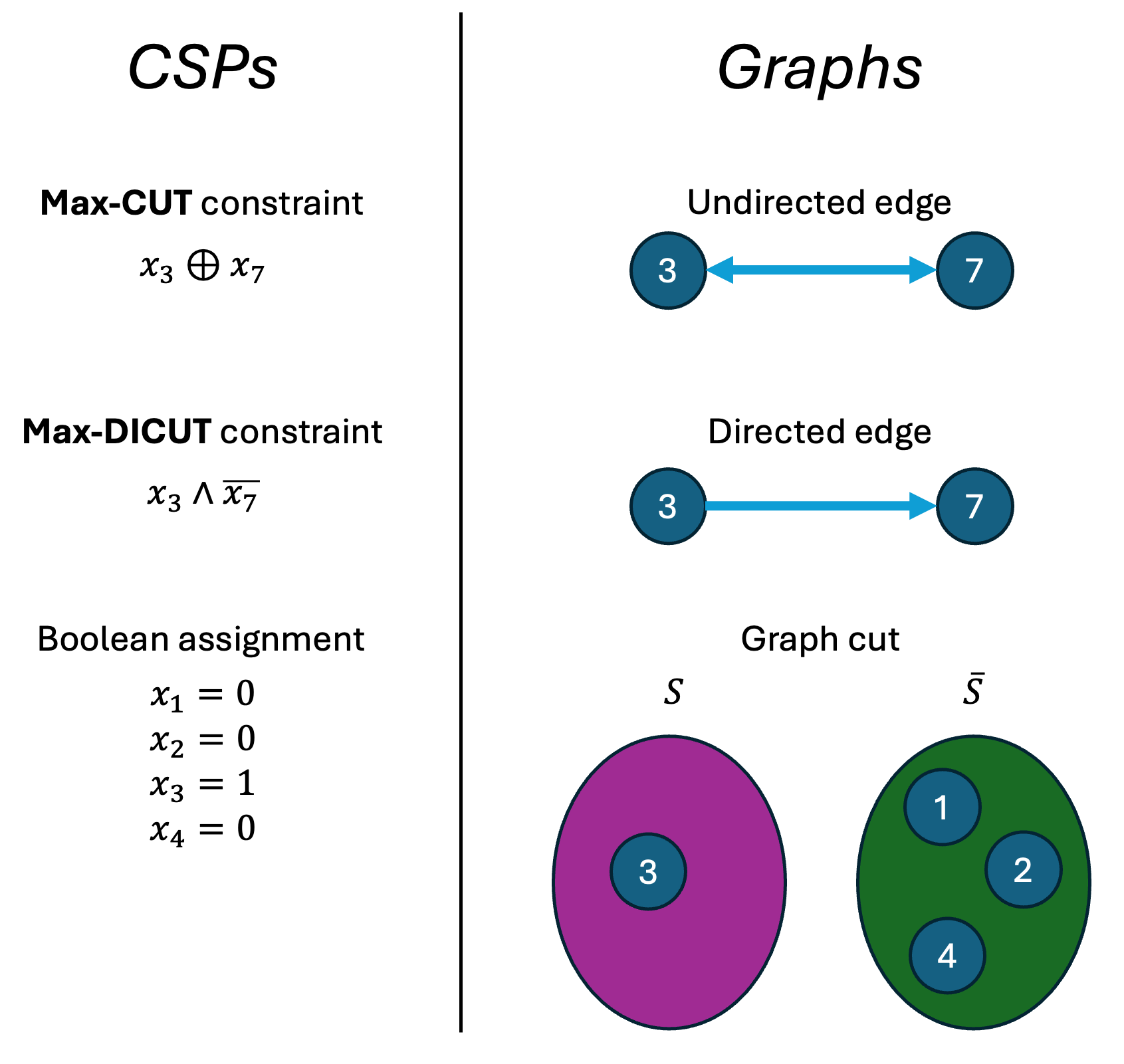

Figure.

A “dictionary” between the CSP and graph versions of

Max-CUT

and

Max-DICUT

. Each variable becomes a vertex, each constraint becomes an edge (directed in

Max-DICUT

, undirected in

Max-CUT

), and a Boolean assignment \(x\) becomes a “cut” of the vertices in the graph.

Figure.

A “dictionary” between the CSP and graph versions of

Max-CUT

and

Max-DICUT

. Each variable becomes a vertex, each constraint becomes an edge (directed in

Max-DICUT

, undirected in

Max-CUT

), and a Boolean assignment \(x\) becomes a “cut” of the vertices in the graph.

Note that in these examples, the arity is a small constant (i.e., either \(2\) or \(3\)). What makes CSPs so interesting is that we can “build up” complicated global instances on arbitrarily many variables by applying predicates to “local” sets of a few variables at a time.

For various reasons, we are interested in studying the feasibility of approximating the values of CSPs (and not exactly determining this value). Firstly, the approximability of CSPs by “classical” (i.e., polynomial-time) algorithms is a subject of intense interest, stemming from connections to probabilistically checkable proofs and semidefinite programming. But the theory of classical CSP approximations relies on unproven assumptions like \(\mathbf{P} \neq \mathbf{NP}\). Space-bounded streaming algorithms generally seem very weak compared to polynomial-time algorithms, but this gives us the satisfaction of proving unconditional hardness results — and some CSPs still admit nontrivial streaming approximation algorithms. Secondly, it turns out that exact computation of CSP value is very hard in the streaming setting. Further, exact computation is hardest for dense instances, which is typical for many streaming problems, while approximation is, interestingly, hardest for sparse instances, i.e., for instances with \(O(n)\) constraints. This is because of the following well-known “sparsification lemma”, which reduces computing the value (approximately) for arbitrary instances to computing the value (approximately) for sparse instances:

Lemma (sparsification, informal) . Let \(\Psi\) be an instance of a CSP with \(n\) variables and \(m\) constraints. Suppose we construct a new instance \(\Psi’\), also on \(n\) variables, but with \(m = \Theta(n)\) constraints, by randomly sampling constraints from \(\Psi\). Then with high probability, the values of \(\Psi\) and \(\Psi’\) will be roughly the same.

(To make this lemma formal: For \(\epsilon > 0\), if \(m’ = \Theta(n/\epsilon^2)\), then we get high probability of the values being within an additive \(\pm\epsilon\). In the unweighted case, “randomly sampling constraints” literally means that each constraint is randomly sampled from \(\Psi\)’s constraints. It is possible to generalize to the weighted case assuming the ratio of maximum to minimum weights is bounded.)

Because of this sparsification lemma, in the remainder of this post, we will assume for simplicity that all CSP instances on \(n\) variables have \(\Theta(n)\) constraints. (Note we are assuming they also have \(\Omega(n)\) constraints. The algorithms we describe below will also work for \(o(n)\) constraints, but this case can sometimes be messier.)

Streaming algorithms meet CSPs: Max-CUT and Max-DICUT

It is natural to ask whether streaming algorithms can use the local constraints defining an instance to deduce something about the quality of the best global assignment:

Key question: How much space does a streaming algorithm need to approximate the value of (the best global assignment to) a CSP given a pass over its list of local constraints?

This question was first posed at the 2011 Bertinoro workshop on sublinear algorithms (see

the

sublinear.info

wiki

). In this section, we examine this question through the lens of

Max-CUT

and

Max-DICUT

, which are two of the simplest and most widely studied Boolean, binary CSPs.

Streaming CSPs and Max-CUT

For the rest of this blog post, we adopt the “graph” language for describing Max-CUT and Max-DICUT . Thus, in the streaming setting, we are interested in algorithms for Max-CUT and Max-DICUT where the input is a stream of undirected edges ( Max-CUT ) or directed edges ( Max-DICUT ) from a graph, and the goal is to output an approximation to the value of the graph.

Now, we turn to some prior results about streaming algorithms for Max-CUT and Max-DICUT . Recall that streaming algorithms are characterized by the amount of space they use. We will be interested in three “regimes” of space. We define these regimes using “\(O\)-tilde” notation: \(g(n) = \tilde{O}(f(n))\) if \(g(n) = O(f(n) \cdot \log^C n)\) for some constant \(C>0\). The regimes are as follows.

Large space

We use “large space” to refer to space between \(\Omega(n)\) and \(\tilde{O}(n)\). This space regime is sufficient to store entire input instances in memory! Thus, we can exactly calculate the value of instances once we see all their constraints, simply by enumerating all possible \(2^n\) global assignments. (Recall that the streaming model places no restrictions on the time usage of algorithms!)

Kapralov and Krachun (STOC’19) showed that for Max-CUT , this algorithm is the best possible: no algorithms using less-than-large space can get a \((1/2+\epsilon)\)-approximation for any \(\epsilon>0\). (\(1/2\)-approximation is “trivial” since every Max-CUT instance has value at least \(1/2\); indeed, a random assignment has expected value \(1/2\) in any instance.) However, the picture for Max-DICUT is much more complicated.

Medium space

We use “medium space” to refer to space between \(\Omega(\sqrt n)\) and \(\tilde{O}(\sqrt n)\). This space regime is important because the “birthday paradox” phenomenon kicks in:

Key fact: Medium space is sufficient to store a set \(S\) of variables large enough that we expect that there are constraints involving at least two variables in \(S\).

Indeed, suppose we have an instance \(\Psi\) on \(n\) variables, we pick a random subset \(S \subseteq [n]\) of \(\Theta(\sqrt n)\) variables, and we look at all constraints which involve at least two variables in \(S\). Each constraint has this property with probability roughly \(\Theta((1/\sqrt n)^2) = \Theta(1/n)\), so by linearity of expectation, we expect roughly \(\Theta(1)\) constraints to have this property.

This key fact implied the breakdown of certain lower bound techniques for problems like Max-DICUT which worked in less-than-medium space, and it is also the starting point for unlocking improved approximation algorithms for Max-DICUT once medium space is available, as we’ll discuss below.

Small space

Finally, we use “small space” to refer to space which is \(\tilde{O}(1)\). Surprisingly, a result of Guruswami, Velingker, and Velusamy (APPROX’17, based out of CMU!) showed that even in small space, there are nontrivial algorithms for Max-DICUT . Chou, Golovnev, and Velusamy (FOCS’20) gave a variant of this algorithm with better approximation guarantees, which they also showed is optimal in less-than-medium space. 4 These algorithms achieve nontrivial approximations in small space by using an important tool from the literature on streaming algorithms: the small-space streaming algorithm, from the seminal work of Indyk (2006), for estimating vector norms.

Max-DICUT and bias

The work of Chou et al. left wide open the gap between medium and large space for approximating Max-DICUT . That is: Are there medium-space (or even less-than-large-space) algorithms which get better approximations than is possible in less-than-medium space? In the next section, I present our affirmative answer to this question, but first, I will introduce a further quantity we will need, which first showed up in this context in the work of Guruswami et al.

Given an instance \(\Psi\) of Max-DICUT (a.k.a., a directed graph), and a vertex \(i \in \{1,\ldots,n\}\), let \(\outdeg_\Psi(i)\) denote the total weight of edges \(i \to i’\), \(\indeg_\Psi(i)\) the total weight of edges \(i’ \to i\), and \(\deg_\Psi(i) = \outdeg_\Psi(i) + \indeg_\Psi(i)\) the total weight of edges \(i_1\to i_2\) in which \(i \in \{i_1,i_2\}\). (These are called, respectively, the out-degree, in-degree, and total-degree of \(i\).) If \(\deg_\Psi(i) > 0\), then we define a scalar quantity called the bias of \(i\): \[ \bias_\Psi(i) := \frac{\outdeg_\Psi(i) - \indeg_\Psi(i)}{\deg_\Psi(i)}. \] Note that \(-1 \leq \bias_\Psi(i) \leq +1\). The quantity \(\bias_\Psi(i)\) captures whether the edges incident to \(i\) are mostly outgoing (\(\bias_\Psi(i) \approx +1\)), mostly incoming (\(\bias_\Psi(i) \approx -1\)), or mixed (\(\bias_\Psi(i) \approx 0\)).

Figure.

Visual depictions of three vertices in a directed graph with biases close to \(+1,0,-1\), respectively. Green edges are outgoing and red edges are incoming.

Figure.

Visual depictions of three vertices in a directed graph with biases close to \(+1,0,-1\), respectively. Green edges are outgoing and red edges are incoming.

This concept of bias, which relies crucially on the asymmetry of the predicate (and therefore has no analogue for Max-CUT ), is the key to unlocking nontrivial streaming approximation algorithms for Max-DICUT . Observe that if e.g. \(\bias_\Psi(i) = -1\), then all edges incident to \(i\) are incoming, and therefore, the optimal assignment for \(\Psi\) should assign \(i\) to \(0\). 5 Indeed, an instance is perfectly satisfiable iff all variables have bias either \(+1\) or \(-1\). What Guruswami et al. showed was that (i) this relationship is “robust”, in that instances with “many large-bias variables” have large value and vice versa, and (ii) whether an instance has “many large-bias variables” can be quantified using small-space streaming algorithms. Chou et al. gave an algorithm with better approximation ratios by strengthening the inequalities in (i).

Remark: While we will not require this below, we mention that the notion of “many large-bias variables” is formalized by a quantity called the total bias of \(\Psi\), which is simply the sum over \(i\), weighted by \(\deg_\Psi(i)\), of \(|\bias_\Psi(i)|\). By definition, the total bias is equal to \(\sum_{i=1}^n |\outdeg_\Psi(i)-\indeg_\Psi(i)|\), which is simply the \(1\)-norm of the vector associated to \(\Psi\) whose \(i\)-th entry is \(\outdeg_\Psi(i)-\indeg_\Psi(i)\)! So the Max-DICUT algorithms of Guruswami et al. and Chou et al. use the small-space \(1\)-norm sketching algorithm of Indyk as a black-box subroutine to estimate the total bias of the input graph.

Improved algorithms from snapshot estimation

Finally, we turn to the improved streaming algorithm for Max-DICUT from our recent papers in (SODA’23, FOCS’23). Our result is the following:

Theorem (Saxena, S., Sudan, Velusamy, FOCS’23). There is a medium-space streaming algorithm for Max-DICUT which achieves an approximation ratio \(\alpha\) strictly larger than the ratio \(\beta\) possible in less-than-medium space (and achievable in small space).

The various results on streaming approximations for Max-DICUT are collected in the following figure:

Figure.

A diagram of the known upper and lower bounds on streaming approximations for

Max-DICUT

. The exponents of \(0,1/2,1\) on the \(x\)-axis correspond to the small-, medium-, and large-space regimes; green dots are prior upper bounds, red dots are prior lower bounds, and the blue dot is our new upper bound. Of note, Chou, Golovnev, and Velusamy showed that \(4/9\)-approximations are achievable in small space and optimal in sub-medium space, while Kapralov and Krachun showed that \(1/2\)-approximations are optimal in sub-large space (where in fact arbitrarily good approximations are known). Our new algorithm gives a \(0.484\)-approximation, lying strictly between \(4/9\) and \(1/2\).

Figure.

A diagram of the known upper and lower bounds on streaming approximations for

Max-DICUT

. The exponents of \(0,1/2,1\) on the \(x\)-axis correspond to the small-, medium-, and large-space regimes; green dots are prior upper bounds, red dots are prior lower bounds, and the blue dot is our new upper bound. Of note, Chou, Golovnev, and Velusamy showed that \(4/9\)-approximations are achievable in small space and optimal in sub-medium space, while Kapralov and Krachun showed that \(1/2\)-approximations are optimal in sub-large space (where in fact arbitrarily good approximations are known). Our new algorithm gives a \(0.484\)-approximation, lying strictly between \(4/9\) and \(1/2\).

The snapshot matrix

To present our algorithm, we first need to define a matrix, which we call the snapshot , associated to any directed graph \(\Psi\). This matrix has the property that a certain linear combination of its entries gives a good approximation to the Max-DICUT value of \(\Psi\) (a better approximation than is possible with a less-than-medium space streaming algorithm). Then, the goal of our algorithm becomes simply estimating the snapshot.

The snapshot matrix is simply the following. Recall that the interval \([-1,+1]\) is the space of possible biases of a variable in a Max-DICUT instance. Fix a partition \(I_1,\ldots,I_B\) of this interval into a finite number of subintervals. Given this partition, we can partition the (positive-degree) variables in \(\Psi\) into “bias classes”: Each vertex \(i \in \{1,\ldots,n\}\) has bias \(\bias_\Psi(i)\) falling into a unique interval \(I_b\) for some \(b \in \{1,\ldots,B\}\). Edges also are partitioned into biases classes: To an edge \(i_1 \to i_2\) in \(\Psi\) we associate class \((b_1,b_2) \in \{1,\ldots,B\} \times \{1,\ldots,B\}\), where \(b_1\) and \(b_2\) are respectively the classes of \(i_1\) and \(i_2\). The snapshot matrix, which we denote \(\mathsf{Snap}_\Psi \in \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}^{B \times B}\), is simply the \(B \times B\) matrix which captures the weight of edges in each bias class, i.e., the \((b_1,b_2)\)-th entry is the total weight of edges \(i_1 \to i_2\) with \(\bias_\Psi(i_1) \in I_{b_1}\) and \(\bias_\Psi(i_2) \in I_{b_2}\).

Aside: Oblivious algorithms

At this point, we can “black-box” the notion of snapshot, since our algorithmic goal is now only to estimate the snapshot. However, to give intuition for the snapshot and show why it lets us achieve good approximations for Max-DICUT , we first take a detour into describing a simple class of “local” algorithms for Max-DICUT . These algorithms, called oblivious algorithms , were introduced by Feige and Jozeph (Algorithmica’17). Again, fix a partition of the space of possible biases \([-1,+1]\) into intervals \(I_1,\ldots,I_B\). For each interval \(I_b\), also fix a probability \(p_b\). Now an oblivious algorithm is one which, given an instance \(\Psi\), inspects each variable \(i\) independently and randomly sets it to \(1\) with probability \(p_b\), where \(b\) is the class of \(i\), and \(0\) otherwise. These algorithms are “oblivious” in the sense that they ignore everything about each variable except its bias.

As discussed in the previous section, in Max-DICUT , if a variable has bias \(+1\), we always “might as well” assign it to \(1\), and if it has bias \(-1\), we “might as well” assign it to \(0\). Oblivious algorithms flesh out this connection by choosing how to assign every variable based on its bias. For instance, if a variable has bias \(+0.99\), we should still want to assign it to \(1\) (at least with large probability).

Feige and Jozeph showed that for a specific choice of the partition \(I_b)\) and probabilities \(p_b)\), the oblivious algorithm gives a good approximation to the overall Max-DICUT value. In particular, we realized the ratio achieved by their oblivious algorithm is strictly better than what Chou et al. showed was possible with a less-than-medium space streaming algorithm. (In a paper of mine at APPROX’23, I generalized this definition and the corresponding algorithmic result to Max-\(k\)AND for all \(k \geq 2\).) Thus, to give improved streaming algorithms it suffices to “simulate” oblivious algorithms (and in particular the oblivious algorithm of Feige and Jozeph).

Figure.

The specific choice of bias partition \(I\) and probabilities \(\pi\) employed by Feige and Jozeph to achieve a \(0.483\)-approximation for

Max-DICUT

. Here, these two objects are presented together as a single step function, with bias on the horizontal axis and probability on the vertical axis. This choice deterministically rounds vertices with bias \(\geq +1/2\) to \(1\), \(\leq -1/2\) to \(0\), and it performs a (discretized version of a) linear interpolation between these extremes for vertices with bias closer to \(0\).

Figure.

The specific choice of bias partition \(I\) and probabilities \(\pi\) employed by Feige and Jozeph to achieve a \(0.483\)-approximation for

Max-DICUT

. Here, these two objects are presented together as a single step function, with bias on the horizontal axis and probability on the vertical axis. This choice deterministically rounds vertices with bias \(\geq +1/2\) to \(1\), \(\leq -1/2\) to \(0\), and it performs a (discretized version of a) linear interpolation between these extremes for vertices with bias closer to \(0\).

The key observation is then that to simulate an oblivious algorithm on an instance \(\Psi\), it suffices to only know (or estimate) the snapshot of \(\Psi\) . Indeed, every edge of class \(b_1, b_2\) is satisfied with probability \((\pi_{b_1})(1-\pi_{b_2})\) (the first factor is the probability that the first endpoint is assigned to \(1\), the second the probability that the second endpoint is assigned to \(0\), and these two events are independent). Thus, by linearity of expectation, the expected weight of the constraints satisfied by the oblivious algorithm is

\[ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}_{x \sim \mathcal{X}}\left[\mathsf{Obl}(\Psi) \right] = \sum_{b_1,b_2 = 1}^B (\pi_{b_1})(1-\pi_{b_2}) \cdot \Snap_\Psi(b_1,b_2). \]

The upshot of this for us is that to estimate the value of an instance \(\Psi\), it suffices to calculate some linear function of this snapshot matrix \(\Snap_\Psi\). Another important consequence of this formula is that it allowed Feige and Jozeph to determine the approximation ratio of any oblivious algorithm using a linear program which minimizes the weight of constraints satisfied over all valid snapshots. 6

A medium-space algorithm and “smoothing” the snapshot

At this point, our goal is to use streaming algorithms to estimate a linear function of the entries of the snapshot \(\Snap_\Psi\). To calculate this function up to a (normalized) \(\pm \epsilon\), it suffices to estimate each entry of the snapshot up to \(\pm \epsilon/B^2\). \(B\) is a constant and so, reparametrizing \(\epsilon\), we seek an algorithm to estimate a given entry of the snapshot up to \(\pm \epsilon\) error.

Recall that the \((b_1,b_2)\)-th entry of the snapshot of \(\Psi\) is the weight of edges in \(\Psi\) with bias class \((b_1,b_2)\), i.e., the weight of edges from bias class \(b_1\) to bias class \(b_2\). To estimate this, we would ideally sample a random set \(E\) of \(T = O(1)\) edges in \(\Psi\), measure the biases of their endpoints, and then use the fraction of edges in the sample with bias class \((b_1,b_2)\) as an estimate for the total fraction of edges with this bias class. But it is not clear how to use a streaming algorithm to randomly sample a small set of edges and measure the biases of their endpoints simultaneously. 7 Indeed, this cannot be possible in small space, since we know via Chou et al. ’s lower bound that medium space is necessary for improved Max-DICUT approximations, and therefore for snapshot estimation! In this final section, we describe how we are able to estimate the snapshot using medium space.

Algorithm for bounded-degree graphs

First, suppose we were promised that in \(\Psi\), every vertex has degree at most \(D\), and \(D = O(1)\). An algorithm to estimate the \((b_1,b_2)\)-th entry of the snapshot of \(\Psi\) in this case is the following:

- Before the stream , sample a set \(S \subseteq \{1,\ldots,n\}\) of \(k\) random vertices, where \(k\) is a parameter to be chosen later.

- During the stream , (i) store all edges whose endpoints are both in \(S\), and (ii) measure the biases of each vertex in \(S\).

- After the stream , take \(E\) to be the set of edges whose endpoints are both in \(S\). Observe that we know the biases of the endpoints of all edges in \(E\), and therefore the bias class of every edge in \(E\). Use the number of edges in \(E\) in bias class \((b_1,b_2)\) to estimate the total number of edges in \(\Psi\) in this bias class.

Observe that the expected number of edges in \(E\) is \(\sim m (k/n)^2\) where \(m\) is the number of edges in \(\Psi\). If \(m = O(n)\), then \(|E| = \Omega(1)\) (in expectation) as long as \(k = \Omega(\sqrt n)\), which is precisely why this algorithm “kicks in” once we have medium space! 8 Once \(S\) is this large, we can indeed show that \(E\) suffices to estimate the snapshot. The proof of correctness of the estimate relies on bounded dependence of \(E\), by which we mean that in the collection of events \(\{e \in E\}_{e \in \Psi}\), each event is independent of all but \(O(1)\) other events. Indeed, observe that since \(\Psi\) has maximum degree \(D\), every edge in \(\Psi\) is incident to \(\leq 2D-1\) other edges. (Two edges are incident if they share at least one endpoint.) And for any two edges \(e, e’ \in \Psi\), the events “\(e \in \Psi\)” and “\(e’ \in \Psi\)” are not independent iff \(e\) and \(e’\) are incident.

The general case

General instances \(\Psi\) need not have bounded maximum degree. This poses a serious challenge for the bounded-degree algorithm we just presented. Consider the case where \(\Psi\) is a “star”, where each edge connects a designated center vertex \(i^*\) to one of the remaining vertices. In this situation, not every vertex is created equal. Indeed, if \(i^* \not\in S\) (which happens asymptotically almost surely), \(E\) will be empty, and therefore we learn nothing about \(\Psi\)’s snapshot.

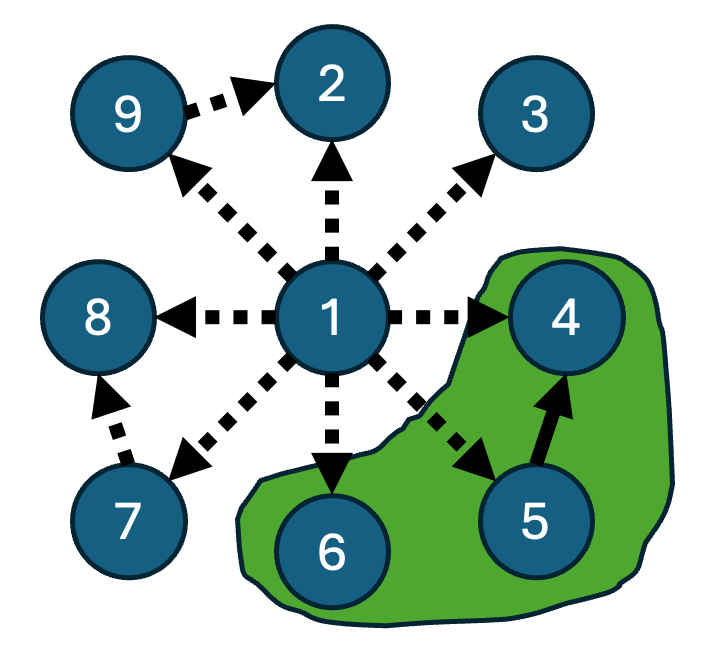

Figure.

An example graph with a highlighted subset of vertices \(S\) (green). Only edges with both endpoints in \(S\) are placed in \(E\) — in this case, there is only a single solid edge. All other edges are not in \(E\). There is a high-degree vertex (\(1\)) which we would ideally put in \(S\): since it is adjacent to so many other vertices, adding it to \(S\) would make \(E\) much larger.

Figure.

An example graph with a highlighted subset of vertices \(S\) (green). Only edges with both endpoints in \(S\) are placed in \(E\) — in this case, there is only a single solid edge. All other edges are not in \(E\). There is a high-degree vertex (\(1\)) which we would ideally put in \(S\): since it is adjacent to so many other vertices, adding it to \(S\) would make \(E\) much larger.

To deal with this issue, the algorithm must become substantially more complex. We design the new algorithm to treat vertices of different degrees differently, giving “higher priority” to storing high-degree vertices, and it also captures more information than the above algorithm — in particular, it stores edges that have one endpoint in the “sampled set”, as opposed to both.

Our new algorithm aims to estimate a more detailed object than the snapshot itself, which we call the refined snapshot of \(\Psi\). To define this object, we also choose a partition into intervals \(J_1,\ldots,J_D\) of the space \([0,O(n)]\) of possible degrees. (We only need that each interval has ratio \(O(1)\) between the minimum and maximum degrees it contains. For simplicity, we pick the intervals to be powers of two: \([1,2), [2,4), [4,8),\ldots\).) This lets us define a unique degree class in \(\{1,\ldots,D\}\) for every vertex, and a corresponding degree class in \(\{1,\ldots,D\}^2\) for every edge. Now the refined snapshot is a four-dimensional array \(\RSnap_\Psi \in \mathbb{R}^{D^2 \times B^2}\), whose \((d_1,d_2,b_1,b_2)\)-th entry is the number of edges in \(\Psi\) with degree class \((d_1,d_2)\) and bias class \((b_1,b_2)\).

Now, how do we estimate entries of this refined snapshot, i.e., estimate the number of edges in \(\Psi\) with degree class \((d_1,d_2)\) and bias class \((b_1,b_2)\)? First, we sample a subset \(\Phi_1 \subseteq \Psi\) of \(\Psi\)’s edges, which I’ll call a slice , in the following way:

- Sample a set \(S_1\) of vertices by including each vertex in \(\{1,\ldots,n\}\) independently w.p. \(p_1\).

- Sample a set \(H_1\) of edges in \(\Psi\) by including each edge in \(\Psi\) independently w.p. \(q_1\).

- \(\Phi_1\) consists of edges in \(H_1\) with at least one vertex in \(S_1\).

Here, \(p_1\) and \(q_1\) are two parameters that depend only on the degree class \(d_1\). We claim that a streaming algorithm can sample a slice (this follows from the definitions), and we observe that this slice can be stored in medium space assuming that \(p_1 q_1 = \tilde{O}(1/\sqrt n)\), since \(\Psi\) has \(O(n)\) edges and therefore \(\Phi_1\) has \(O(p_1q_1n)\) edges in expectation. We repeat the above process to produce a second slice \(\Phi_2\), with corresponding parameters \(p_2,q_2\), and then use the slices \(\Phi_1,\Phi_2\) to calculate our estimate of the snapshot.

The choices of \(p_1,q_1,p_2,q_2\) are delicate. Taking \(p_1,q_1\) as an example, if the highest degree in class \(J_{d_1}\) is constant, then we pick \(p_1=\Theta(1/\sqrt n)\) and \(q_1 = 1\), and our algorithm recovers the bounded-degree algorithm above. But in general, \(q_1\) is chosen so that vertices in degree-class \(J_{d_1}\) have expected constant degree in \(H_1\), which allows us to recover similar “bounded dependence” behavior to the bounded-degree algorithm and therefore get concentration in the estimate.

But still, how does the algorithm use the slices \(\Phi_1,\Phi_2\) to estimate the snapshot entry? Let \(W_1\) denote the set of “target” vertices in \(\Psi\) which actually have bias class \(b_1\) and degree class \(d_1\). Similarly, define \(W_2\) as the “target” vertices in bias class \(b_2\) and degree class \(d_2\). The \((d_1,d_2,b_1,b_2)\)-th entry of the snapshot is then simply \(|\Psi \cap (W_1 \times W_2)|\). Let \(V_1 = W_1 \cap S_1\) and \(V_2 = W_2 \cap S_2\). Suppose that the algorithm, in addition to the slices \(\Phi_1,\Phi_2\), received \(V_1,V_2\) as its input. Now note that for any edge \(e = (v_1,v_2) \in \Psi \cap (W_1 \times W_2)\), the event “\(e \in \Phi_1 \cap (V_1 \times V_2) \)” has probability \(p_1 p_2 q_1\), since the events “\(v_1 \in S_1\)”, “\(v_2 \in S_2\)”, and “\(e \in H_1\)” are all independent. We could therefore hope to use \(|\Phi_1 \cap (V_1 \times V_2)|\) to estimate the snapshot entry; 9 indeed, (assuming that \(d_1 < d_2\)) this turns out to be true, and the proof goes by first conditioning on \(H_1\), and then arguing that given \(H_1\), degrees are sufficiently small to imply bounded dependence of which edges are in \(\Phi_1\) over the choice of \(S_1,S_2\).

But unfortunately, the algorithm does not get to see the actual sets \(V_1\) and \(V_2\). Instead, we have to employ certain “proxy” sets \(\hat{V}_1,\hat{V}_2\). To define these sets, observe that in the graph \(H_1\), for every vertex \(v \in \{1,\ldots,n\}\), \[ \mathbb{E}_{H_1}[\deg_{H_1}(v)] = q_1 \cdot \deg_{\Psi}(v). \] Thus, by just looking at the slice \(\Phi_1\), we can estimate the degree of every vertex in \(S_1\). We can similarly estimate the bias, since \[ \mathbb{E}_{H_1}[\bias_{H_1}(v)] = \bias_\Psi(v). \] So, given \(\Phi_1\) we can define a set \(\hat{V}_1 \subseteq \{1,\ldots,n\}\) of vertices in \(S_1\) which appear to have bias class \(b_1\) and degree class \(d_1\), based on their estimated degrees and biases in the slice. \(\hat{V}_1\) is an “estimate” for \(V_1\), and similarly we can define \(\hat{V}_2\) “estimating” \(V_2\) using the second slice \(\Phi_2\).

Smoothing the snapshot

There is an additional complication caused by using “estimated” sets \(\hat{V}_1,\hat{V}_2\) instead of the actual sets \(V_1,V_2\): It is not improbable for there to be “extra” or “missing” vertices in the estimated sets. Suppose, for instance, there is a vertex \(v\) which is in degree class \(d_1+1\), but whose degree is close to the lower limit of the interval \(J_{d_1+1}\). Then \(v\) is by definition not in \(V_1\), but depending on the randomness of \(H_1\), it could end up in \(\hat{V}_1\) with decent probability. This means we actually cannot estimate any particular entry of the refined snapshot with good probability!

To deal with this issue, we slightly modify the underlying problem we are trying to solve: Instead of aiming to directly estimate the refined snapshot, we aim to estimate a “smoothed” version of this snapshot, where the entries “overlap”, in that each entry captures edges whose bias and degree classes fall into certain “windows”. More precisely, for some window-size parameter \(w\), the \((d_1,d_2,b_1,b_2)\)-th entry captures the number of edges whose degree class is in \(\{d_1-w,\ldots,d_1+w\} \times \{d_2-w,\ldots,d_2+w\}\) and bias class class is in \(\{b_1-w,\ldots,b_1+w\} \times \{b_2-w,\ldots,b_2+w\}\). Each particular vertex will fall into many (\(\sim w^4\)) of these windows, meaning that any errors from mistakenly shifting a vertex into adjacent bias or degree classes are “averaged out” for sufficiently large \(w\). Finally, we show that estimating the “smoothed” snapshot is still sufficient to estimate the Max-DICUT value using a continuity argument, essentially because slightly perturbing vertices’ biases cannot modify the Max-DICUT value too much.

Conclusion

Several interesting open questions remain after the above results on streaming algorithms for Max-DICUT . Firstly, it would be interesting to extend these results to other CSPs besides Max-DICUT . For instance, we know of analogues for oblivious algorithms for Max-\(k\)AND for all \(k \geq 2\), but whether there are snapshot estimation algorithms that “implement” these oblivious algorithms in less-than-large space is an open question. Also, there is a yawning gap between medium and large space. Proving any approximation impossibility result, or constructing better approximation algorithms, in the between-medium-and-large space regime would be very exciting. We do mention that the snapshot-based approach cannot give optimal (i.e., ratio-\(1/2\)) approximations for Max-DICUT because of another result of Feige and Jozeph, namely, a pair of graphs \(\Psi,\Phi\) which have the same snapshot, but the ratio of their Max-DICUT values is strictly less than \(1/2\).

Bibliography

J. Boyland, M. Hwang, T. Prasad, N. Singer, and S. Velusamy, “On sketching approximations for symmetric Boolean CSPs,” in Approximation, Randomization, and Combinatorial Optimization. Algorithms and Techniques , A. Chakrabarti and C. Swamy, Eds., in LIPIcs, vol. 245. Schloss Dagstuhl — Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, Jul. 2022, p. 38:1–38:23. doi: 10.4230/LIPIcs.APPROX/RANDOM.2022.38 .

C.-N. Chou, A. Golovnev, and S. Velusamy, “Optimal Streaming Approximations for all Boolean Max-2CSPs and Max-\(k\)SAT,” in IEEE 61st Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science , IEEE Computer Society, Nov. 2020, pp. 330–341. doi: 10.1109/FOCS46700.2020.00039 .

U. Feige and S. Jozeph, “Oblivious Algorithms for the Maximum Directed Cut Problem,” Algorithmica , vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 409–428, Feb. 2015, doi: 10.1007/s00453-013-9806-z .

V. Guruswami, A. Velingker, and S. Velusamy, “Streaming Complexity of Approximating Max 2CSP and Max Acyclic Subgraph,” in Approximation, randomization, and combinatorial optimization. Algorithms and techniques , K. Jansen, J. D. P. Rolim, D. Williamson, and S. S. Vempala, Eds., in LIPIcs, vol. 81. Schloss Dagstuhl — Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, Aug. 2017, p. 8:1-8:19. doi: 10.4230/LIPIcs.APPROX-RANDOM.2017.8 .

P. Indyk, “Stable distributions, pseudorandom generators, embeddings, and data stream computation,” J. ACM , vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 307–323, May 2006, doi: 10.1145/1147954.1147955

M. Kapralov, S. Khanna, and M. Sudan, “Streaming lower bounds for approximating MAX-CUT,” in Proceedings of the 26th Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms , Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Jan. 2015, pp. 1263–1282. doi: 10.1137/1.9781611973730.84 .

M. Kapralov and D. Krachun, “An optimal space lower bound for approximating MAX-CUT,” in Proceedings of the 51st Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing, Association for Computing Machinery, Jun. 2019, pp. 277–288. doi: 10.1145/3313276.3316364 .

N. G. Singer, “Oblivious algorithms for the Max-\(k\)AND problem,” in Approximation, Randomization, and Combinatorial Optimization. Algorithms and Techniques , N. Megow and A. D. Smith, Eds., in LIPIcs, vol. 275. May 2023. doi: 10.4230/LIPIcs.APPROX/RANDOM.2023.15 .

R. R. Saxena, N. G. Singer, M. Sudan, and S. Velusamy, “Streaming complexity of CSPs with randomly ordered constraints,” in Proceedings of the 2023 Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms , Jan. 2023. doi: 10.1137/1.9781611977554.ch156 .

R. R. Saxena, N. Singer, M. Sudan, and S. Velusamy, “Improved streaming algorithms for Maximum Directed Cut via smoothed snapshots,” in IEEE 63rd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science , IEEE Computing Society, 2023, pp. 855–870. doi: 10.1109/FOCS57990.2023.00055 .

More precisely, this typically means that the object is “far from” the set of objects having \(P\) in some mathematical sense. For instance, if the objects are graphs and the property \(P\) is the graph property of bipartiteness, “really not having \(P\)” might mean that many edges in the graph must be added or deleted in order to get \(P\) to hold.

This is in contrast to more traditional areas of theory, such as time complexity, where many impossibility results are “conditional” on conjectures like \(\mathbf{P} \neq \mathbf{NP}\).

It is also interesting to study minimization versions of CSPs (i.e., trying to minimize the number of unsatisfied constraints), but that is out of scope for this post.

Specifically, Chou et al. showed a sharp threshold in the space needed for \(4/9\)-approximations. The analysis of their algorithm was subsequently simplified in a joint work of mine with Boyland, Hwang, Prasad, and Velusamy in (APPROX’21).

More precisely, there exists an optimal assignment with this property.

This is an oversimplification: The goal is to minimize the approximation ratio (i.e., the value of the oblivious assignment over the value of the optimal assignment). However, Feige and Jozeph observe that under a symmetry assumption for \(\pi\), it suffices to only minimize over instances where (i) the (unnormalized) value of the instance is \(1\) and (ii) the all-\(1\)’s assignment is optimal. Given (i), the algorithm’s ratio on an instance is simply the (unnormalized) expected value of the assignment produced by the oblivious algorithm, and (i) and (ii) together can be implemented as an additional linear constraint in the LP.

This task is easier in some “nonstandard” streaming models. Firstly, suppose we were guaranteed that the edges showed up in the stream in a uniformly random order . Then since the first \(T\) edges in the stream are a random sample of \(\Psi\)’s edges, we could simply use these edges for our set \(E\), and then record the biases of their endpoints over the remainder of the stream. Alternatively, suppose we were allowed two passes over the stream of edges. We could then use the first pass to sample \(T\) random edges \(E\), and use the second pass to measure the biases of their endpoints. Both of these algorithms use small space, since we are only sampling a constant number of edges.

To avoid having to sample \(S\) upfront and store it, it turns out to be instead sufficient to use a \(4\)-wise independent hash function.

It turns out to be important for the concentration bounds that we use the slice with smaller degree, e.g., if \(d_1 < d_2\) then we count edges in \(\Phi_1\). In this case, if we instead counted edges in \(\Phi_2\), the expectation would be \(O(p_1 p_2 q_2 m)\), which could be smaller than \(1\) if \(d_2\) is very large.

More precisely, for all \(\epsilon>0\) these algorithms output some value \(\hat{v}\) satisfying \(\hat{v} \in (1\pm\epsilon) \|\mathbf{v}\|_p\) with high probability, and use \(O(\log n/\epsilon^{O(1)})\) space.

See 8 .