Next: VHPOP at IPC3 Up: VHPOP: Versatile Heuristic Partial Previous: Conflict-Driven Flaw Selection.

In classical planning, actions have no duration: the effects of an action are instantaneous. Many realistic planning domains, however, require actions that can overlap in time and have different duration. The version of the planning domain definition language (PDDL), PDDL2.1, that was used for IPC3 introduces the notion of durative actions. A durative action represents an interval of time, and conditions and effects can be associated with either endpoint of this interval. Durative actions can also have invariant conditions that must hold for the entire duration of the action.

We use the constraint-based interval approach to temporal POCL planning described by Smith et al. (2000), which in essence is the same approach as used by earlier temporal POCL planners such as DEVISER (Vere, 1983), ZENO (Penberthy & Weld, 1994), and IXTET (Ghallab & Laruelle, 1994). Like IXTET, we use a simple temporal network (STN) to record temporal constraints. The STN representation allows for rapid response to temporal queries. ZENO, on the other hand, uses an integrated approach for handling both temporal and metric constraints, and does not make use of techniques optimized for temporal reasoning. The following is a description of how VHPOP handles the type of temporal planning domains expressible in PDDL2.1.

When planning with durative actions, we substitute the partial order

![]() in the representation of a plan with an STN

in the representation of a plan with an STN

![]() . Each action ai of a plan, except the dummy actions

a0 and a

. Each action ai of a plan, except the dummy actions

a0 and a![]() , is represented by two nodes t2i-1 (start

time) and t2i (end time) in the STN

, is represented by two nodes t2i-1 (start

time) and t2i (end time) in the STN

![]() , and

, and

![]() can be compactly represented by the d-graph

(Dechter et al., 1991). The d-graph is a complete

directed graph, where each edge

ti

can be compactly represented by the d-graph

(Dechter et al., 1991). The d-graph is a complete

directed graph, where each edge

ti ![]() tj is labeled by

the shortest temporal distance, dij, between the two time nodes

ti and tj (i.e.

tj - ti

tj is labeled by

the shortest temporal distance, dij, between the two time nodes

ti and tj (i.e.

tj - ti ![]() dij). An additional time

point, t0, is used as a reference point to represent time zero. By

default,

dij =

dij). An additional time

point, t0, is used as a reference point to represent time zero. By

default,

dij = ![]() for all i

for all i ![]() j (

dii = 0),

signifying that there is no upper bound on the difference tj - ti.

j (

dii = 0),

signifying that there is no upper bound on the difference tj - ti.

Constraints are added to

![]() at the addition of a new

action, the linking of an open condition, and the addition of an

ordering constraint between endpoints of two actions.

at the addition of a new

action, the linking of an open condition, and the addition of an

ordering constraint between endpoints of two actions.

The duration, ![]() , of a durative action ai is specified as a

conjunction of simple duration constraints

, of a durative action ai is specified as a

conjunction of simple duration constraints

![]()

![]() c, where

c is a real-valued constant and

c, where

c is a real-valued constant and ![]() is in the set

{ = ,

is in the set

{ = , ![]() ,

, ![]() }.4 Each simple

duration constraint gives rise to temporal constraints between the

time nodes t2i-1 and t2i of

}.4 Each simple

duration constraint gives rise to temporal constraints between the

time nodes t2i-1 and t2i of

![]() when adding ai

to a plan

when adding ai

to a plan

![]()

![]() ,

,![]() ,

,![]() ,

,![]()

![]() . The temporal constraints, in terms of the minimum distance

dij between two time points, are as follows:

. The temporal constraints, in terms of the minimum distance

dij between two time points, are as follows:

| Duration Constraint | Temporal Constraints |

|---|---|

|

|

d2i-1, 2i = c and d2i, 2i-1 = - c |

|

|

d2i-1, 2i |

|

|

d2i, 2i-1 |

The semantics of PDDL2.1 with durative actions dictates that every

action be scheduled strictly after time zero. Let ![]() denote

the smallest fraction of time required to separate two time points.

To ensure that an added action ai is scheduled after time zero, we

add the temporal constraint

d2i-1, 0

denote

the smallest fraction of time required to separate two time points.

To ensure that an added action ai is scheduled after time zero, we

add the temporal constraint

d2i-1, 0 ![]() -

- ![]() in addition to

any temporal constraints due to duration constraints.

Figure 2(a) shows the matrix representation of the d-graph

after adding an action, a1, with duration constraint

in addition to

any temporal constraints due to duration constraints.

Figure 2(a) shows the matrix representation of the d-graph

after adding an action, a1, with duration constraint

![]()

![]() 7

7![]()

![]()

![]() 3 to a null plan. The rows and columns of the

matrix correspond to time point 0, the start of action a1, and

the end of action a1 in that order. After adding action a2 with

duration constraint

3 to a null plan. The rows and columns of the

matrix correspond to time point 0, the start of action a1, and

the end of action a1 in that order. After adding action a2 with

duration constraint

![]() = 4, we have the d-graph represented by

the matrix in Figure 2(b). The two additional rows and

columns correspond to the start and end of action a2 in that order.

= 4, we have the d-graph represented by

the matrix in Figure 2(b). The two additional rows and

columns correspond to the start and end of action a2 in that order.

![\begin{figure}\centering\subfigure[]{$\left(\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & \infty & \in...

...nfty & 0 & 4 \\

-5 & \infty & \infty & -4 & 0

\end{array}\right)$}

\end{figure}](img53.png) |

A temporal annotation

![]()

![]() {s, i, e} is added to the representation of open conditions. The open

condition

{s, i, e} is added to the representation of open conditions. The open

condition

![]() ai represents a condition that must

hold at the start of the durative action ai,

ai represents a condition that must

hold at the start of the durative action ai,

![]() ai represents a condition that must hold at

the end of ai, while

ai represents a condition that must hold at

the end of ai, while

![]() ai is an invariant

condition for ai. An equivalent annotation is added to the

representation of causal links. The linking of an open condition

ai is an invariant

condition for ai. An equivalent annotation is added to the

representation of causal links. The linking of an open condition

![]() ai to an effect associated with a time point tj

gives rise to the temporal constraint

dkj

ai to an effect associated with a time point tj

gives rise to the temporal constraint

dkj ![]() -

- ![]() (k = 2i

if

(k = 2i

if

![]() = e, else k = 2i - 1). Figure 2(c) shows the

representation of the STN for a plan with actions a1 and a2, as

before, and with an effect associated with the end of a2 linked to

a condition associated with the end of a1.

= e, else k = 2i - 1). Figure 2(c) shows the

representation of the STN for a plan with actions a1 and a2, as

before, and with an effect associated with the end of a2 linked to

a condition associated with the end of a1.

Unsafe causal links are resolved in basically the same way as before,

but instead of adding ordering constraints between actions we add

temporal constraints between time points ensuring that one time point

precedes another time point. We can ensure that time point ti

precedes time point tj by adding the temporal constraint

dji ![]() -

- ![]() .

.

Every time we add a temporal constraint to a plan, we update all

shortest paths dij that could have been affected by the added

constraint. This propagation of constraints can be carried out in

O(|![]() |2) time.

|2) time.

Once a plan without flaws is found, we need to schedule the actions in

the plan, i.e. assign a start time and duration for each action. A

schedule of the actions is a solution to the STN

![]() , and a

solution assigning the earliest possible start time to each action is

readily available in the d-graph representation. The start time of

action ai is set to

- d2i-1, 0 (Corollary 3.2,

Dechter et al., 1991) and the duration to

d2i-1, 0 - d2i, 0. Assuming Figure 2(c) represents the

STN for a complete plan, then we would schedule a1 at time 1 with

duration 5 and a2 at time 1 with duration 4. We can easily

verify that this schedule is indeed consistent with the duration

constraints given for the actions, and that a2 ends before a1 as

required.

, and a

solution assigning the earliest possible start time to each action is

readily available in the d-graph representation. The start time of

action ai is set to

- d2i-1, 0 (Corollary 3.2,

Dechter et al., 1991) and the duration to

d2i-1, 0 - d2i, 0. Assuming Figure 2(c) represents the

STN for a complete plan, then we would schedule a1 at time 1 with

duration 5 and a2 at time 1 with duration 4. We can easily

verify that this schedule is indeed consistent with the duration

constraints given for the actions, and that a2 ends before a1 as

required.

Each non-durative action can be treated as a durative action of fixed duration 0, with preconditions associated with the start time, effects associated with the end time, and without any invariant conditions. This allows for a frictionless treatment of domains with both durative and non-durative actions.

Let us for a moment consider the memory requirements for temporal POCL

planning compared to classical POCL planning. When planning with

non-durative actions, we store

![]() as a bit-matrix

representing the transitive closure of the ordering constraints in

as a bit-matrix

representing the transitive closure of the ordering constraints in

![]() . For a partial plan with n actions, this requires

n2 bits. With n durative actions, on the other hand, we need

roughly 4n2 floating-point numbers to represent the d-graph of

. For a partial plan with n actions, this requires

n2 bits. With n durative actions, on the other hand, we need

roughly 4n2 floating-point numbers to represent the d-graph of

![]() . Each floating-point number requires at least 32 bits

on a modern machine, so in total we need more than 100 times as many

bits to represent temporal constraints as regular ordering constraints

for each plan. We note, however, that each refinement changes only a

few entries in the d-graph, and by choosing a clever representation of

matrices we can share storage between plans. The upper left 3×3 sub-matrix in Figure 2(b) is for example identical to the

matrix in Figure 2(a). The way we store matrices in

VHPOP allows us to exploit this commonality and thereby

reduce the total memory requirements.

. Each floating-point number requires at least 32 bits

on a modern machine, so in total we need more than 100 times as many

bits to represent temporal constraints as regular ordering constraints

for each plan. We note, however, that each refinement changes only a

few entries in the d-graph, and by choosing a clever representation of

matrices we can share storage between plans. The upper left 3×3 sub-matrix in Figure 2(b) is for example identical to the

matrix in Figure 2(a). The way we store matrices in

VHPOP allows us to exploit this commonality and thereby

reduce the total memory requirements.

The addition of durative actions does not change the basic POCL

algorithm. The recording of temporal constraints and temporal

annotations can be handled in a manner transparent to the rest of the

planner. The search heuristics described in Section 3,

although not tuned specifically for temporal planning, can be used

with durative actions. We only need to slightly modify the definition

of literal and action cost in the additive heuristic because of the

temporal annotations associated with preconditions and effects of

durative actions. Let

![]() s(q) denote the set of

ground actions achieving q at the start, and

s(q) denote the set of

ground actions achieving q at the start, and

![]() e(q) the set of ground actions achieving q

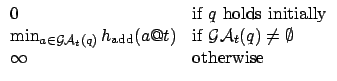

at the end. We define the cost of the literal q as

e(q) the set of ground actions achieving q

at the end. We define the cost of the literal q as

,

,

Håkan L. S. Younes