Carnegie Mellon Photo Editing Tool Enables Object Images To Be Manipulated in 3-D With Help of Stock 3-D Models, Photographed Items Can Be Turned, Flipped, Animated

Byron SpiceTuesday, August 5, 2014Print this page.

PITTSBURGH—Editors of photos routinely resize objects, or move them up, down or sideways, but Carnegie Mellon University researchers are adding an extra dimension to photo editing by enabling editors to turn or flip objects any way they want, even exposing surfaces not visible in the original photograph.

A chair in a photograph of a living room, for instance, can be turned around or even upside down in the photo, displaying sides of the chair that would have been hidden from the camera, yet appearing to be realistic.

This three-dimensional manipulation of objects in a single, two-dimensional photograph is possible because 3-D numerical models of many everyday objects — furniture, cookware, automobiles, clothes, appliances — are readily available online. The research team led by Yaser Sheikh, associate research professor of robotics, found they could create realistic edits by fitting these models into the geometry of the photo and then applying colors, textures and lighting consistent with the photo.

“In the real world, we’re used to handling objects — lifting them, turning them around or knocking them over,” said Natasha Kholgade, a Ph.D. student in the Robotics Institute and lead author of the study. “We’ve created an environment that gives you that same freedom when editing a photo.”

Kholgade will present the team’s findings Aug. 13 at the SIGGRAPH 2014 Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques in Vancouver, Canada. (A video demonstrating the new system is available below.)

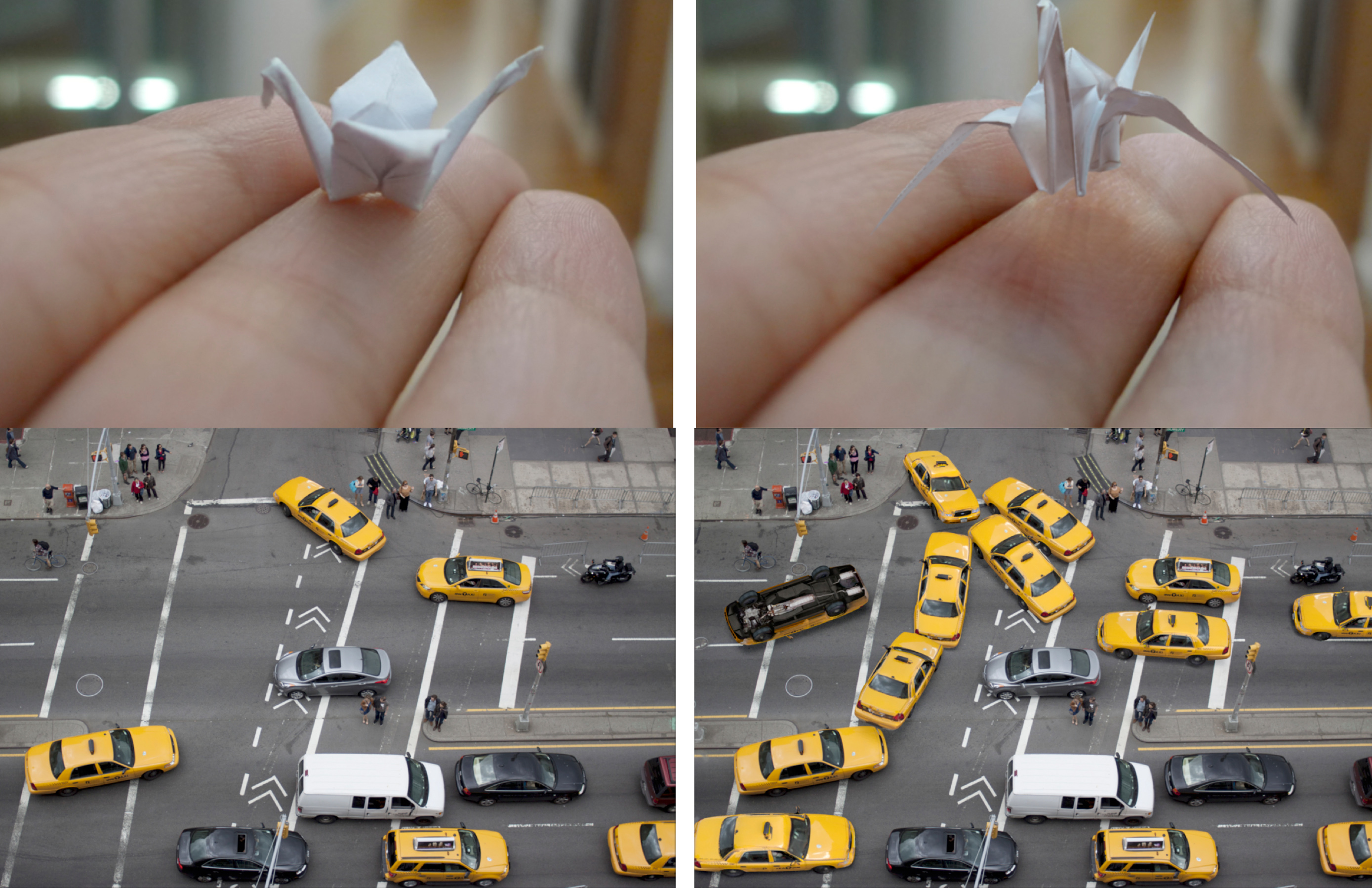

Though the system is designed for use with digital imagery, it enables the same 3-D manipulation of objects in paintings and historical photos. Objects that can be manipulated in photos can also be animated. The researchers demonstrated that an origami bird held in a hand can be made to flap its wings and fly away, or a taxicab shown in a street scene can levitate, flip over to reveal its undercarriage and zip off into the heavens.

“Instead of simply editing ‘what we see’ in the photograph, our goal is to manipulate ‘what we know’ about the scene behind the photograph,” Kholgade said.

Other researchers have used depth-based segmentation to perform viewpoint changes in photos or have used modeling of photographed objects, but neither approach enables hidden areas to be revealed. Another alternative is to insert a new 2-D or 3-D object into a photo, but those approaches discard information from the original photo regarding lighting and appearance, so the results are less than seamless.

One of the catches to using publicly available 3-D models is that the models seldom, if ever, fit a photo exactly. Variations occur between the models and the physical objects. Real-life objects such as seat cushions and backpacks are sometimes deformed as they are used, and appearances may change because of aging, weathering or lighting.

To fix these variations, the researchers developed a technique to semi-automatically align the model to the geometry of the object in the photo while preserving the symmetries in the object. The system then automatically estimates the environmental illumination and appearance of the hidden parts of the object — the visible side of a seat cushion or of a banana is used to create a plausible appearance for the opposite side. If the photo doesn’t contain pertinent appearance information — such as the underside of a taxicab — the system uses the appearance of the stock 3-D model.

Though a wide variety of stock models is available online, models are not available for every object in a photo. But that limitation is likely to subside, particularly as 3-D scanning and printing technologies become ubiquitous. “The more pressing question will soon be not whether a particular model exists online, but whether the user can find it,” Sheikh said. One thrust of future research will need to be automating the search for 3-D models in a database of millions.

This research was sponsored in part by a Google Research Award. In addition to Kholgade and Sheikh, the team included Tomas Simon, a Ph.D. student in the Robotics Institute, and Alexei Efros, a former CMU faculty member who is now an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of California, Berkeley.

The Robotics Institute is part of Carnegie Mellon’s top-rankedSchool of Computer Science, which is celebrating its 25th year. Follow the school on Twitter @SCSatCMU.

Byron Spice | 412-268-9068 | bspice@cs.cmu.edu