SCS Research Highlights Kids' Role in AI

Marylee WilliamsTuesday, December 3, 2024Print this page.

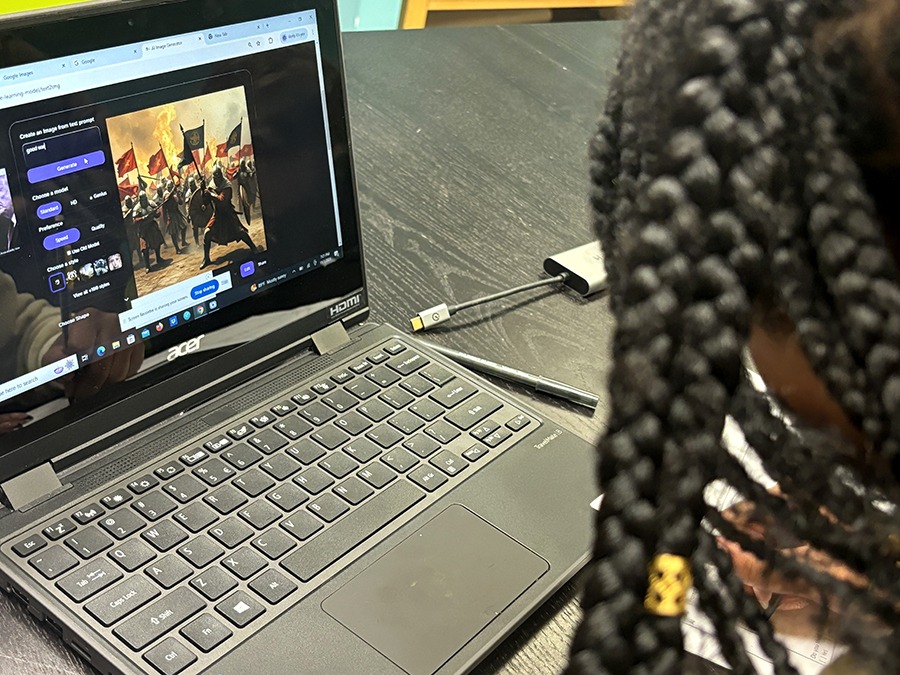

Seated at a laptop and surrounded by other students, a young girl asked an image generator powered by artificial intelligence to create a picture of a good war. She turned to the moderator to show her screen, which displayed two opposing armor-clad battalions poised in the middle of a battlefield, weapons and flags raised, but not fighting.

The girl was one of 15 middle and high school students who participated in a series of workshops at Carnegie Mellon University's School of Computer Science that sought to understand how young people use generative AI tools.

Researchers at SCS want to know how AI tools impact kids and families, and how kids can be empowered to analyze and improve AI tools. Jaemarie Solyst, a doctoral student in the Human Computer Interaction Institute (HCII) who researches responsible AI, ran the workshops. Solyst examines how these tools can impact marginalized communities — which includes young people — with colleagues Motahhare Eslami, an assistant professor in the HCII; and Amy Ogan and Jessica Hammer, both HCII associate professors focused on learning sciences.

"Kids are so curious about technology, and they often find themselves using AI-driven technologies that are not necessarily youth-specific," Solyst said. "In my research, I see that kids as young as 9 are using generative AI tools for their homework and certainly other things, too. They're regularly using social media, search engines and other tools that were not designed with youth in mind for learning, entertainment or social connection. With kids having so much interaction with AI, we need to understand what their unique experiences are with these tools and treat them as a different demographic than adults."

Participants in the first workshop learned the basics of AI and were asked to get creative and input a text prompt into an AI image generator that would deliver a result they thought was wrong. But they also had to consider what "wrong" meant. Did it mean the image was factually inaccurate? Warped? Or was it something more nuanced, such as biased?

Laughter and gasps broke through the ambient soft click of keyboard strikes as the participants reacted to the generative AI program's ridiculous outputs. Kids asked these programs to create images of Area 51, political figures hugging and brain rot. They ended up with warped faces, aliens and a transparent skull with a red brain.

Solyst ran six workshops, some with only students and others that included parents. She said when it comes to AI tools and the design process, people's ideas about who is using AI tools don't necessarily align with reality. Even though young people often use these tools, the adults who design and build them do so without kids' input and without them in mind.

Earlier this year, Solyst, Eslami, Hammer and Ogan published work on middle-school-aged girls' overtrust in these AI systems. Middle school is a critical time for developing girls' interest in STEM careers, and, as women, they are likely to experience bias in AI. The study also used workshops to engage students, bringing together youth to foster communication.

"Peer-to-peer collaborative discussion can help demystify some misperceptions or some of the nuances in these topics," Eslami said. "We found the workshop settings more practical, more efficient and also, because of this group dynamic, more effective for youth learning."

Researchers in the middle-grade study found that participants did overtrust AI systems, believing the large language model (LLM) ChatGPT delivered correct answers when some were incorrect. One example from the study was a math problem, "Compute 32874 x 34918." Participants thought the LLM gave the correct answer when it was actually wrong. Eslami said the kids assumed the answer was correct because the information was presented in an official-looking way — known as aesthetic legitimacy — and with perceived transparency because the LLM showed the steps it took to get the answer.

Eslami echoed Solyst, saying that kids access these tools as part of their everyday lives, and that its vital to instill in young people that these systems are fallible, can spread misinformation and cause harm. Eslami stressed that young people are affected by these tools, and the creators should design them with youth in mind.

"When today's teenagers were born, a lot of these AI systems were already out, such as virtual assistants and search engines," she said. "It's important to break overtrust now, because it's really difficult later."

Back on the CMU campus, the participants in Solyst's workshops explored the social power dynamics of AI systems using a website she and her research team created called MPower (short for "mapping power"). The tool allowed students to think creatively about how an AI system could go wrong, who would be affected by the system and what actions stakeholders could take to address those issues. Solyst said the students in this workshop enjoyed playfully designed aspects of the tool, such as assigning an emoji to each stakeholder, as they learned about complex societal aspects of AI, including how AI systems impact communities at scale.

As the workshops wrapped up, the students' genuine curiosity and expertise about AI impressed Solyst.

"Young people, as end users of these AI tools, can provide useful insights in auditing such systems as either experts in a certain field or simply from their experience as young people," she said.

For example, one of the participating students was a textile artist and her knowledge of crocheting meant she could identify when the AI system generated incorrect images of crocheted clothes. Also, in general, social media trends move quickly, and young people are more likely to have insights into them on apps like TikTok.

Solyst said questions remain on how and to what extent young people can audit and improve these systems because youth have useful lived experiences.

"Overall, this study really motivates the inclusion of youth. Of course, there's still a lot of open-ended queries like how exactly we involve them and what serious topics may be more or less fitting for certain populations," Solyst said. "The goal isn't to have the onus be on kids to fix these problems. Instead, we want them to be able to critically navigate AI systems around them, as well as understand empowering pathways to engage as stakeholders in responsibly creating AI if they want to."

Researchers plan to apply what they learned from these workshops to several studies to better understand things like how youth can be part of the design process for creating more responsible AI.

Aaron Aupperlee | 412-268-9068 | aaupperlee@cmu.edu