What Virtual Zebrafish Can Teach Us About Autonomous AI

Marylee WilliamsThursday, January 8, 2026Print this page.

The Breakdown

- Researchers developed an AI agent that exhibited similar behaviors to a real zebrafish.

- The 3M-Progress algorithm doesn't use reward motivation. Instead, the AI agents have a kind of curiosity that allows them to explore.

- This work could be an early step toward "AI agent scientists" that can investigate complex information without bias and find new insights in large datasets.

***

Aran Nayebi jokes that his robot vacuum has a bigger brain than his two cats. But while the vacuum can only follow a preset path, Zoe and Shira leap, play and investigate the house with real autonomy.

"I see them flexibly play and jump around," Nayebi said. "Their brains are so much tinier than the Roomba, yet these animals have a kind of robust agency."

This natural curiosity seen in animals inspired Nayebi and his Carnegie Mellon University colleagues to try to build something that can explore its environment without explicitly being told what to do. The work hints at a future where autonomous "AI agent scientists" could sift through massive, complex datasets without human bias, uncovering patterns and insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

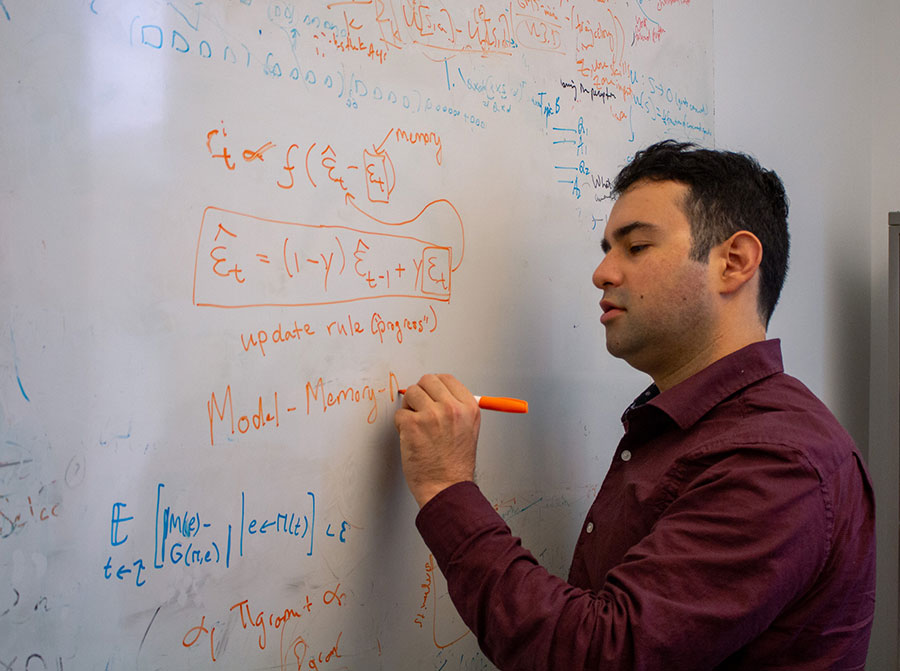

Nayebi, an assistant professor in the Machine Learning Department (MLD) in CMU's School of Computer Science, is part of a research team that created a virtual zebrafish that acted like a real zebrafish without any prior training. The virtual zebrafish replicated animal-like brain activity and exhibited animal-like autonomy in a simulated environment.

That autonomy is critical when developing AI agents for open-ended exploration without clearly defined goals — that is, creating AI agent scientists.

"If we build AI scientists, we could take those moments of serendipity in scientific discovery, like how penicillin was discovered, and make them more likely," Nayebi said. "In biology, for example, data has lots of connected components that all influence each other, and AI agents are better at handling more information."

The agents might also perform better than humans because they won't have the biases that people do. Biology has shown that humans are interested in narratives and crafting stories that can often lead to misleading or underpowered conclusions. Nayebi said an AI agent is intrinsically focused on what is supported by the data.

Nayebi and the team chose a zebrafish because of prior research biologists did into the glial cells in their brains. Initially, glial cells were understudied, but the biologists discovered that the cells play a role in the larval zebrafish's ability to swim and explore their environment.

When biologists severed the zebrafish's ability to use its tail, it could no longer swim and entered futility-induced passivity, which means that it tried hard to swim, realized it couldn't and stopped moving for a while. After some time in this passive state, the zebrafish tried again, and it was the interactions with the glial cells that helped it try again.

Nayebi and the team used this prior research to develop a computational method that lets an AI agent explore and adapt to its environment without any external rewards or labeled data. Their simulated larval zebrafish uses the model, called Model-Memory-Mismatch Progress or 3M-Progress, to understand its world.

The memory component of the model is twofold. It is both a current memory, like that of real-time experiences of its world, and an "ethologically relevant prior memory," which is a prior memory of how its world should work, such as if the zebrafish moves its tail, it will move through the water. The mismatch occurs when there is a new sensory experience that doesn't match the prior memory, causing it to update its model — or understanding of the world.

"Our research shows that existing approaches to intrinsic curiosity aren't flexible enough to capture real animal exploration," said Reece Keller, a Ph.D. student in the Neuroscience Institute (NI) and the Robotics Institute (RI). "Incorporating memory primitives, which are fixed priors about the world that the agent can remember and reference later, gives just enough flexibility to construct an intrinsic goal that not only captures zebrafish exploration behavior, but also predicts whole-brain activity at single-cell resolution from our agent's artificial brain. This is important because it emphasizes that animal intelligence is built on top of lots of biological priors."

3M-Progress is an intrinsic-motivation algorithm, meaning it gives an AI agent its own built-in drive to explore rather than relying on external rewards. For example, a robot vacuum is a reward-based AI agent. It doesn't explore the space; it makes a map and is then "rewarded" when it effectively cleans the mapped area. The simulated zebrafish isn't simply searching for new stimuli or white noise. Instead, the mismatch signal pushes the agent toward meaningful, curiosity-like exploration.

"In the past, people have trained a virtual rodent by taking videos of rodents running, tracking them and then training reinforcement learning policies to mimic that movement directly in the video," Nayebi said. "But here, we're not doing that. We're training this virtual zebrafish with a 3M-Progress objective. This virtual zebrafish hasn't been shown how real zebrafish move, and we're not trying to force its 'brain' to match the data directly. Instead, we created a simulated environment, let it explore and evaluated its behavior afterward."

Researchers then recreated the situation from previous research that led to the futility-induced passivity to see if the simulated zebrafish would enter that state without prior training. They found that the virtual zebrafish showed behavior similar to futility-induced passivity. Nayebi said the result is significant because the virtual zebrafish exhibited this kind of behavior without any prior knowledge of the state.

"What we learned from previous research is that the neural glial connection is just the way that biology instantiates that mismatched computation, when the lived experience isn't aligning with expectations," he said. "In real-life larval zebrafish, the glia are that circuit that computes the mismatch and then suppresses the motion of the fish. What we found with our simulated zebrafish is that when we train the model to basically track its progress, it's learning to do a similar thing where it realizes it's futile and then it suppresses its actions and then starts up again. You get this cyclical behavior, and that's the futility-induced passivity."

Recreating this behavior in an AI agent helps researchers understand and get one step closer to recreating animal-like autonomy in AI agents. Nayebi said this work is just beginning, and as researchers tackle more complex problems that the brain has also solved, the solutions become more and more similar to how the brain actually works because there are so few solutions to begin with.

Along with Nayebi and Keller, the CMU research team included Alyn Kirsch, a master's student in RI; Felix Pei, a Ph.D. student in the NI; and Xaq Pitkow, an NI associate professor. The team also included Leo Kozachkov, who is an assistant professor at Brown University.

Nayebi said the team's next steps include exploring how autonomy can be applied across different embodiments, not just zebrafish.

Aaron Aupperlee | 412-268-9068 | aaupperlee@cmu.edu