Next: Computation of tupled values Up: Graduality in Argumentation Previous: Acknowledgements

In this section, we give the proofs of all the properties presented in Sections 3 and 4.

Proof

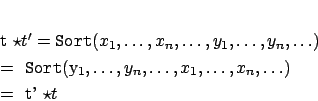

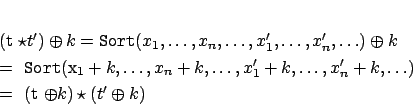

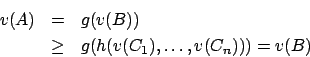

(of Property 1) By induction fromand by applying function

twice.

Proof

(of Property 2) The valuation functionassociates each argument

with a value

belonging to a set

which is a subset of a completely ordered set

.

Proof

(of Property 3) Letbe a cycle:

However, the ![]() may have different values: for

example, for

may have different values: for

example, for ![]() , with the valuation of [13],

, with the valuation of [13], ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() .

If all the

.

If all the ![]() have the same value, then this value will be a

fixpoint of

have the same value, then this value will be a

fixpoint of ![]() (because

(because

![]() ).

).

Since the function ![]() is non-increasing, the function

is non-increasing, the function ![]() is also non-increasing and we can apply the following result: ``if a

non-increasing function has fixpoints, these fixpoints are

identical''30.

So,

is also non-increasing and we can apply the following result: ``if a

non-increasing function has fixpoints, these fixpoints are

identical''30.

So,

![]() . But,

. But,

![]() , so

, so ![]() is a fixpoint of

is a fixpoint of ![]() .

.

So, for all the

![]() ,

, ![]() is a fixpoint of

is a fixpoint of ![]() .

.

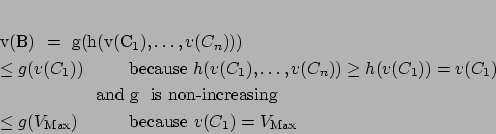

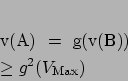

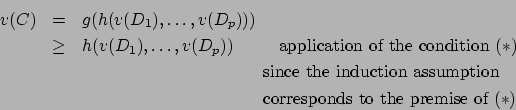

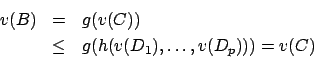

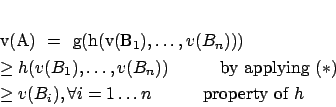

Proof

(of Property 4)

P1 is satisfied because:, if

has no direct attacker (

is empty), then

and

.

P2 is satisfied because if,

evaluates the ``direct attack'' of

.

P3 is satisfied because the functionis supposed to be non-increasing.

P4 is satisfied due to the properties of the function.

Proof

(of Property 5) The valuation proposed by [13] is the following:

Letbe an argumentation system. A complete labelling of

is a function

such that:

Moreover, [13] also defines a complete rooted labellingwith:

, if

then

such that

.

The translation ofinto a local gradual valuation is very easy:

is defined by

,

,

and

is the function

.

Proof

(of Property 6) [4] introduces the following function(in the context of ``deductive'' arguments and for an acyclic graph):

The translation ofinto a gradual valuation is:

,

,

and

and

is defined by

and

is defined by

.

Proof

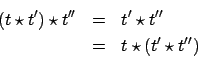

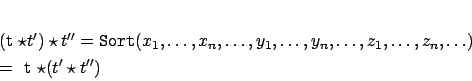

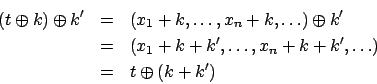

(of Property 7) Let,

,

be tuples.

Proof

(of Property 9) First, we show that the relationdefined by Algorithm 1 is a partial ordering:

Let,

,

be three tupled values, the relation

defined by Algorithm 1 is:

Now, consider the maximal and minimal values:

Proof

(of Property 10) The principle P1is satisfied by Definition 10 and by the fact that

is the unique maximal element of

(see Property 9).

The principle P2is satisfied because of Definition 10.

The principles P3and P4

are satisfied: all the possible cases of improvement/degradation of the defence/attack for a given argument (see Definition 16) are applied case by case31. Each case leads to a new argument. Using Algorithm 1, the comparison between the argument before and after the application of the case shows that the principle P3

(or P4

, depending on the applied case) is satisfied.

Proof

(of Property 11) From Definition 10.

Proof

(of Property 12) First, we consider the case of the preferred extensions: Letbe a preferred extension

, we assume that

does not contain all the unattacked arguments of

. So, let

be an unattacked argument such that

.

Consider:

So, the assumption ``does not contain all the unattacked arguments of

'' cannot hold.

Now, we consider stable extensions: Letbe a stable extension

, we assume that

does not contain all the unattacked arguments of

. So, let

be an unattacked argument such that

.

Sincethere exists in

another argument

which attacks

; This is impossible since

is unattacked.

So, the assumption ``does not contain all the unattacked arguments of

'' cannot hold.

Proof

(of Property 13) An argument and one of its direct attackers cannot belong to the same extension in the sense of [9] because the extension must be conflict-free. So, sinceis uni-accepted, it means that

belongs to all the extensions, and none of the direct attackers of

belongs to these extensions.

For the converse, we use the following counterexample in the case of the preferred semantics:

There are two preferred extensions and

. The argument

is cleanly-accepted (

and

do not belong to any preferred extension, and

belongs to at least one of the two extensions). But,

is not uni-accepted because it does not belong to all preferred extensions.

Proof

(of Property 14) First,uni-accepted

cleanly-accepted is the result of Property 13.

Conversely, letbe a cleanly-accepted argument, there exists at least one stable extension

such that

and

,

,

stable extension. Using a reductio ad absurdum, we assume that there exists a stable extension

such that

; but, if

, it means that

such that

, so, the direct attacker

of

belongs to a stable extension; so, there is a contradiction with the assumption (

is cleanly-accepted); so,

does not exist and

is uni-accepted.

Proof

(of Theorem 1)

The constraints from ![]() to

to ![]() are the following:

are the following:

So, for the path

![]() , the set of the

well-defended arguments is

, the set of the

well-defended arguments is

![]() if

if ![]() is odd,

is odd,

![]() otherwise

(this is the set of all the arguments having a value strictly

better than those of their direct attackers). This set will

denoted by ACCEP

otherwise

(this is the set of all the arguments having a value strictly

better than those of their direct attackers). This set will

denoted by ACCEP![]() .

.

By definition, this set is conflict-free, it defends all its

elements (because it contains only the leaf of the path and all

the arguments which are defended by this leaf) and it attacks all

the other arguments of the path. If we try to include another

argument of the path

![]() ACCEP

ACCEP![]() , we obtain a conflict (because all the other arguments of the path are attacked by the

elements of ACCEP

, we obtain a conflict (because all the other arguments of the path are attacked by the

elements of ACCEP![]() ). So, for

). So, for

![]() , ACCEP

, ACCEP![]() is the only preferred and stable extension.

is the only preferred and stable extension.

Consider

![]() , with

, with

![]() being the

restriction of

being the

restriction of ![]() to

to

![]() 32 and UNIONACCEP

32 and UNIONACCEP![]() ACCEP

ACCEP![]() , then UNIONACCEP

is the only

preferred and stable extension of

, then UNIONACCEP

is the only

preferred and stable extension of

![]() .

.

So,

![]() ,

, ![]() is accepted iff

is accepted iff ![]() well-defended.

well-defended.

Using the following example, we show that the converse is false:

![% latex2html id marker 11151

\includegraphics[scale=0.6]{/home/lagasq/recherche/argumentation/eval-accep/JAIR-final/cex-rac-dep2.eps}](img716.png)

![]() is well-defended (

is well-defended (![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() is

incomparable with

is

incomparable with ![]() ) but not accepted.

) but not accepted.

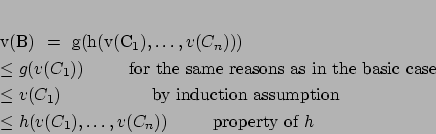

Proof

(of Lemma 1) Letbe an argumentation system with a finite relation

without cycles (so, there is only one non empty preferred and stable extension denoted by

). We know that:

The proof is done by induction on the depth of a proof tree foror

.

so:

But, Property 1 says that

![]() , so

, so

![]() .

.

So:

and with the non-increasing of ![]() :

:

so:

so:

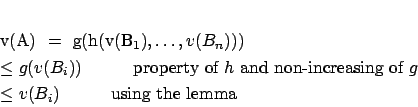

Proof

(of Theorem 2) Assume thatis true and consider

which is exi-accepted. Let

,

, be the direct attackers of

. Then, for all

, in the subgraph leading to

and completed with

, we apply the lemma and we obtain:

,

. Thus, we have:

So,is well-defended.

For the converse, letbe well-defended. Let

be the direct attackers of

and assume that

is not exi-accepted. Then, there exists at least one direct attacker

of

such that

is exi-accepted (because there is only one preferred and stable extension). We can apply

of the lemma on the subgraph leading to

completed with

and we obtain

. So, there exists

a direct attacker of

such that:

This is in contradiction withwell-defended. So,

is exi-accepted.

Marie-Christine Lagasquie 2005-02-04